JavaScript is an interesting language and we all love it because of its nature. Browsers are the home for JavaScript and both work together at our service.

JS has a few concepts where people tend to take it lightly and sometime may tumble over. Concepts like prototyping, closures and event-loops are still one of those obscure areas where most of the JS developers take a detour. And as we know “little knowledge is a dangerous thing”, it may lead to making mistakes.

Let’s play a mini-game where I am going to ask you a few questions and you have to try answering all of them. Make a guess even if you don’t know the answer or if it’s out of your knowledge. Note down your answers and then check the corresponding answers below. Give yourself a score of 1 for each correct answer. Here we go.

Disclaimer: I’ve used ‘var’ purposely in some of the following code snippets so that you guys can copy paste them into your browser’s console without running into SyntaxError problem.

But I don’t condone the usage of ‘var’ declared variables. ‘let’ and ‘const’ declared variables make your code robust and less error-prone.

Question 1: What will be printed on the browser console?

var a = 10;

function foo() {

console.log(a); // ??

var a = 20;

}

foo();

Question 2: Will output be the same if we use let or const instead of var?

var a = 10;

function foo() {

console.log(a); // ??

let a = 20;

}

foo();

Question 3: What elements will be in the “newArray”?

var array = [];

for(var i = 0; i <3; i++) {

array.push(() => i);

}

var newArray = array.map(el => el());

console.log(newArray); // ??

Question 4: If we run the ‘foo’ function in the browser console, will it cause a stack overflow error?

function foo() {

setTimeout(foo, 0); // will there by any stack overflow error?

};

Question 5: Will the UI of the page (tab) remains responsive if we run the following function in the console?

function foo() {

return Promise.resolve().then(foo);

};

Question 6: Can we somehow use the spread syntax for the following statement without causing a TypeError?

var obj = { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3 };

[...obj]; // TypeError

Question 7: What will be printed on the console when we run the following code snippet?

var obj = { a: 1, b: 2 };

Object.setPrototypeOf(obj, {c: 3});

Object.defineProperty(obj, 'd', { value: 4, enumerable: false });

// what properties will be printed when we run the for-in loop?

for(let prop in obj) {

console.log(prop);

}

Question 8: What value xGetter() will print?

var x = 10;

var foo = {

x: 90,

getX: function() {

return this.x;

}

};

foo.getX(); // prints 90

var xGetter = foo.getX;

xGetter(); // prints ??

Answers

Now, let’s try to answer each question from top to bottom. I will give you a brief explanation while trying to demystify these behaviors along with some references.

Answer 1: undefined.

Explanation: The variables declared with var keywords are hoisted in JavaScript and are assigned a value of undefined in the memory. But initialization happens exactly where you typed them in your code. Also, var-declared variables are function-scoped, whereas let and const have block-scoped. So, this is how the process will look like:

var a = 10; // global scope

function foo() {

// Declaration of var a will be hoisted to the top of function.

// Something like: var a;

console.log(a); // prints undefined

// actual initialisation of value 20 only happens here

var a = 20; // local scope

}

Answer 2: ReferenceError: a is not defined.

Explanation: let and const allows you to declare variables that are limited in scope to the block, statement, or expression on which it is used. Unlike var, these variables are not hoisted and have a so-called temporal dead zone (TDZ). Trying to access these variables in TDZ will throw a ReferenceError because they can only be accessed until execution reaches the declaration. Read more about lexical scoping and Execution Context & Stack in JavaScript.

var a = 10; // global scope

function foo() { // enter new scope, TDZ starts

// Uninitialised binding for 'a' is created

console.log(a); // ReferenceError

// TDZ ends, 'a' is initialised with value of 20 here only

let a = 20;

}

The following table outlines the hoisting behaviour and scoping associated with different keywords used in JavaScript (credit: Axel Rauschmayer's blog post).

Answer 3: [3, 3, 3].

Explanation: Declaring a variable with var keyword in the head of for loop creates a single binding (storage space) for that variable. Read more about closures. Let’s look at the for loop one more time.

// Misunderstanding scope:thinking that block-level scope exist here

var array = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

// Every 'i' in the bodies of the three arrow functions

// referes to the same binding, which is why they all

// return the same value of '3' at the end of the loop.

array.push(() => i);

}

var newArray = array.map(el => el());

console.log(newArray); // [3, 3, 3]

If you let-declare a variable, which has a block-level scope, a new binding is created for each loop iteration.

// Using ES6 block-scoped binding

var array = [];

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

// This time, each 'i' refers to the binding of one specific iteration

// and preserves the value that was current at that time.

// Therefore, each arrow function returns a different value.

array.push(() => i);

}

var newArray = array.map(el => el());

console.log(newArray); // [0, 1, 2]

Another way of solving this quirk would be to use closures.

// After understanding static scoping and thus closures.

// Without static scoping, there's no concept of closures.

let array = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

// invoking the function to capture (closure) the variable's current value in the loop.

array[i] = (function(x) {

return function() {

return x;

};

})(i);

}

const newArray = array.map(el => el());

console.log(newArray); // [0, 1, 2]

Answer 4: No.

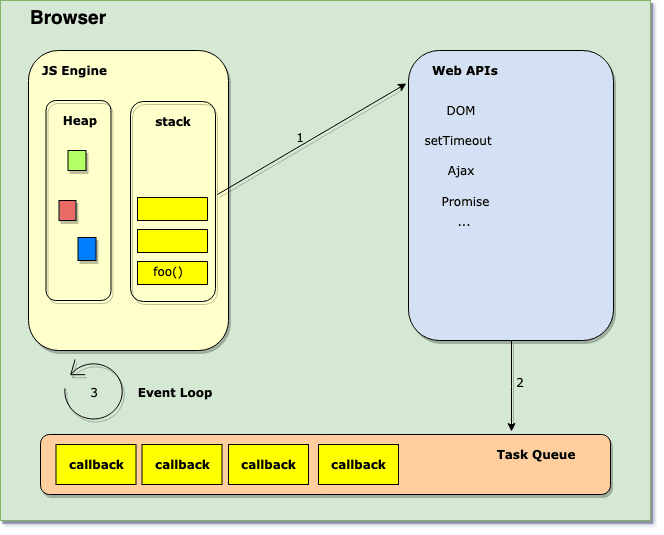

Explanation: JavaScript concurrency model is based on an “event loop”. When I said “Browsers are the home for JS”, what I really meant was that browsers provide runtime environment to execute our JavaScript code. The main components of the browser include Call stack, Event loop, Task Queue and Web APIs. Globals functions like setTimeout, setInterval, and Promise are not the part of JavaScript but the Web APIs. The visual representation of the JavaScript environment can be something like as shown below:

JS call stack is Last In First Out (LIFO). The engine takes one function at a time from the stack and runs the code sequentially from top to bottom. Every time it encounters some asynchronous code, like setTimeout, it hands it over to the Web API (arrow 1). So, whenever an event is triggered, the callback gets sent to the Task Queue (arrow 2).

The Event loop is constantly monitoring the Task Queue and process one callback at a time in the order they were queued. Whenever the call stack is empty, the loop picks up the callback and put it into the stack (arrow 3) for processing. Keep in mind that if call stack is not empty, event loop won’t push any callbacks to the stack.

For a more detailed description of how Event loop works in JavaScript, I highly recommend watching this video by Philip Roberts. Additionally, you can also visualise and understand the call stack via this awesome tool. Go ahead and run the ‘foo’ function there and see what happens!

Now, armed with this knowledge, let’s try to answer the aforementioned question:

Steps

- Calling foo() will put the foo function into the call stack.

- While processing the code inside, JS engine encounters the setTimeout.

- It then hands over the foo callback to the WebAPIs (arrow 1) and returns from the function. The call stack is empty again.

- The timer is set to 0, so the foo will be sent to the Task Queue (arrow 2).

- As, our call stack was empty, the event loop will pick the foo callback and push it to the call stack for processing.

- The Process repeats again and stack doesn't overflow ever.

Answer 5: No.

Explanation: Most of the time, I have seen developers assuming that we have only one task queue in the event loop picture. But that’s not true. We can have multiple task queues. It’s up to the browser to pick up any queue and processes the callbacks inside.

On a high level, there are macrotasks and microtasks in JavaScript. The setTimeout callbacks are macrotasks whereas Promise callbacks are microtasks. The main difference is in their execution ceremony. Macrotasks are pushed into the stack one at a time in a single loop cycle, but the microtask queue is always emptied before execution returns to the event loop including any additionally queued items. So, if you were adding items to this queue as quickly you’re processing them, you are processing micro tasks forever. For a more in-depth explanation, watch this video or article by Jake Archibald.

Microtask queue is always emptied before execution returns to the event loop

Now, when you run the following code snippet in your console:

function foo() {

return Promise.resolve().then(foo);

};

Every single invocation of ‘foo’ will continue to add another ‘foo’ callback on the microtask queue and thus the event loop can’t continue to process your other events (scroll, click etc) until that queue has completely emptied. Consequently, it blocks the rendering.

Answer 6: Yes, by making object iterables.

Explanation: The spread syntax and for-of statement iterates over data that iterable object defines to be iterated over. Array or Map are built-in iterables with default iteration behaviour. Objects are not iterables, but you can make them iterable by using iterable and iterator protocols.

In Mozilla documentation, an object is said to be iterable if it implements the @@iterator method, meaning that the object (or one of the objects up its prototype chain) must have a property with a @@iterator key which is available via constant Symbol.iterator.

The aforesaid statement may seem a bit verbose, but the following example will make more sense:

var obj = { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3 };

obj[Symbol.iterator] = function() {

// An iterator is an object which has a next method,

// which also returns an object with atleast

// one of two properties: value & done.

// returning an iterator object

return {

next: function() {

if (this._countDown === 3) {

return { value: this._countDown, done: true };

}

this._countDown = this._countDown + 1;

return { value: this._countDown, done: false };

},

_countDown: 0

};

};

[...obj]; // will print [1, 2, 3]

You can also use a generator function to customize iteration behaviour for the object:

var obj = { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3 };

obj[Symbol.iterator] = function*() {

yield 1;

yield 2;

yield 3;

};

[...obj]; // print [1, 2, 3]

Answer 7: a, b, c.

Explanation: The for-in loop iterates over the enumerable properties of an object itself and those the object inherits from its prototype. An enumerable property is one that can be included in and visited during for-in loops.

var obj = { a: 1, b: 2 };

var descriptor = Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, "a");

console.log(descriptor.enumerable); // true

console.log(descriptor);

// { value: 1, writable: true, enumerable: true, configurable: true }

Now having this knowledge in your bag, it should be easy to understand why our code printed those specific properties:

var obj = { a: 1, b: 2 }; // a, b are both enumerables properties

// setting {c: 3} as the prototype of 'obj', and as we know

// for-in loop also iterates over the properties obj inherits

// from its prototype, 'c' will also be visited.

Object.setPrototypeOf(obj, { c: 3 });

// we are defining one more property 'd' into our 'obj', but

// we are setting the 'enumerable' to false. It means 'd' will be ignored.

Object.defineProperty(obj, "d", { value: 4, enumerable: false });

for (let prop in obj) {

console.log(prop);

}

// it will print

// a

// b

// c

Answer 8: 10.

Explanation: When we initialised x into the global scope, it becomes the property of the window object (assuming that it’s a browser environment and not a strict mode). Looking at the code below:

var x = 10; // global scope

var foo = {

x: 90,

getX: function() {

return this.x;

}

};

foo.getX(); // prints 90

let xGetter = foo.getX;

xGetter(); // prints 10

We can assert that:

window.x === 10; // true

this will always point to the object onto which the method was invoked. So, in the case of foo.getX(), this points to foo object returning us the value of 90. Whereas in the case of xGetter(), this points to the window object returning us the value of 10.

To retrieve the value of foo.x, we can create a new function by binding the value of this to the foo object using Function.prototype.bind.

let getFooX = foo.getX.bind(foo);

getFooX(); // prints 90

That’s all! Well done if you’ve got all of your answers correct. We all learn by making mistakes. It’s all about knowing the ‘why’ behind it. Know your tools and know them better. If you liked the article, a few ❤️ will definitely make me smile 😀.

What was your score anyway 😃?

Top comments (31)

I did these all wrong! How can I bring back my confidence...

Hi Sten, lemme tell you a few things here:

Firstly, when I asked these questions to my fellow workers, most of them couldn't answer them right. So, it's completely fine if you got all of these wrong. Important thing is that now you know a few things.

Secondly, building confidence takes some time. And accepting what you don't know is the first step towards it. We all have been through a stage a not knowing anything. The important part is how much efforts you put into learning these new things.

Here are a few things I do to build up my confidence:

Consistency always beats Intelligence. 😀

Thanks for sharing these stuff Amendeep! I'll keep up learning JavaScript and hopefully someday I can share something valuable for the community like you.

Glad to read that.😃

I guess at some stage every Javascript developer gets all of these wrong . It’s good thing to know that you don’t know something , you can now learn them .

you funny js, stop it...

Here's your answer to this.

0.30000000000000004.com

JavaScript is funny I know, but not this much 🤣

sure it is

{} + []

0

Well, to answer this question, here's how ECMAScript 2019 defines the

Addition operator. ecma-international.org/ecma-262/#s.... The run time has a few steps to follow before it spits out the result.{} + [] = 0

Before we understand how did we get that strange result, we need to dive into how type conversion a.k.a "Coercion" works in JavaScript.

Abstract operations are the fundamental building blocks that makes up how we deal with coercion. Abstract Operation fundamentally performs the type conversion for us.

By the way, Abstract operations are not the functions which get called. By calling them abstract, we mean they’re conceptual operations. These operations are not a part of the ECMAScript language; they are defined here to solely to aid the specification of the semantics of the ECMAScript language.

In our case, we are trying to do a numeric operation with 2 non-primitive types i.e an object and an array. So, to perform this numeric operation JS needs to convert them into primitives first i.e Numbers in our case. So if we have something non-primitive, like one of the object types like an object, an array, and a function and we need to make it into a primitive, there is an Abstract method named ToPrimitive which is going to get involved in doing that.

So any time you have something that is not primitive and it needs to become primitive, conceptually, what we need to do is this set of algorithmic steps, and that's called ToPrimitive as if it were a function that could be invoked.

ToPrimitive

The ToPrimitive abstract operation takes an optional type hint. So it says like “If you have something which is not primitive, tell me what do you think you would like, what type you would want it to be ?” If you are doing a numeric operation and it invokes ToPrimitive, guess what’s hint it’s gonna send in? - A Number. That doesn’t guarantee a number but it’s just a hint to say that the place I’m using it requires it to be a number. There can basically be 2 types of hints that can be sent i.e number and string.

Another thing we need to understand is that the algorithms within JS are inherently recursive, which means that they define something, for example - ToPrimitive and if the returned result from ToPrimitive is not Primitive, then it's gonna get invoked again and it's gonna keep getting invoked until we get something that's an actual Primitive or in some cases an error.

How does ToPrimitive works ?

The way it works is that there are 2 methods that can be available on any non-primitive i.e valueOf() and toString(). This algorithm says, if you've told me that the hint is number, then I'm going to first try to invoke the valueOf() function if it's there, and see what it gives me. And if it gives me a primitive then we're done. If it doesn't give me a primitive, or it doesn't exist, then we try the toString(). If we try both of those and we don't get a primitive, generally that's gonna end up resulting in an error. That happens when the hint is number. If the hint was string, they just reverse the order that they consult them in.

When JS executes {}+[], the following things happen -

As we are doing a numeric operation and we need primitives, ToPrimitive method gets called with "number" as a hint when we try to convert [].

As we know ToPrimitive calls 2 methods i.e valueOf() and toString() in an order depending on the hint. In this case, the hint was a number so valueOf() function is invoked.

For an array or an object, by default, the valueOf method essentially returns itself. Which has the effect of just ignoring the valueOf and deferring to toString(). So it doesn't even matter that the hint was number. It just goes directly goes to *toString() *.

Without further digression, let's answer the question []+{} = 0

When the parser sees that there is { at the beginning of a statement, it treats it as a block. In our case {} as no statements inside it hence it has empty continuation value. {} in our case is just an empty block which doesn't have any impact on the given statement.

Now coming down +[] statement, coercion kicks in here. [] is a non-primitive type which needs to be converted to Primitive and due to the + operator, it passes "number" as a hint to ToPrimitive which further calls valueOf() which defers it to toString() method.

"" is a primitive type which is returned from the ToPrimitive operation.

Now we have +"", again coercion kicks in and calls another abstract method ToNumber() which converts every non-numeric primitive to numeric primitive.

We are now left with +0 which is equals to 0.Here we have solved it, {} + [] = 0

Thanks Malkeet for your time writing an in-depth explanation of how addition operators works. This comment can be turned into a single blog post. Would love to see that happen. ❤️❤️😍

why ? it comes like this

my answers:

I got the easy ones correct.

about 5. Honestly wasn't sure :D

about 6. I basically haven't got time to learn and play with with >= ES6.

Well done 🙂. There are more new features coming up in ES2019. This is right time to invest into learning ES6 if you haven't started yet. Good luck 👍

Hey,

I think that's a really good and useful article

For the sixth answer, I made a bit another approach

what do you think about that?

It makes me sure that I don't need to worry about new or old values

This is a beautiful approach Max. 😀

For other people to understand, let me explain Max's approach here:

The takeaway is:

amazing post, opened doors of my perception, things like microtasks and macrotasks are new to me, thanks!😁

Glad to read that. Thank you for your nice comment about the post.

This is a really great post. Would love to see more like this. JavaScript is full of interesting idiosyncrasies.

Thanks for your nice words Yonas. Looking forward to creating a part 2 of this. 🙂

Thank you for your kind words. I am looking forward to create part 2 of this series. 😃

Very interesting. Specifically i liked the iterable one.

Glad that you liked it.Thanks for reading. 😃

Great post, would like to see more like this 👍

My answers to 2, 5 and 6 were wrong. I need to schedule some time to fill the gaps.

Thank you Eugene for your words. I am looking forward to creating another one like this soon. 😃

I did 7 of 8, don't stop at the top :) excellent post

Well played Daniel. Thanks for your nice words too 😃