Last year I started working with JavaScript as my main language. It was a fresh experience coming from C# and Java. But after a while I've got annoyed with Type errors, while Eslint helps to avoid typos, types weren't its thing. Add to that the cognitive load it comes from remembering every function argument. I understand that naming can help, but a little bit. Typescript fixed these both issues for me, now I don't need to worry about a React component prop or function.

Typescript also has great support in Vscode, spotting errors while coding. It also highlights types for easy scanning. Okay enough hype, for now, time to explain what I learned in past months.

Building Blocks

This article won't go into typescript basic syntax nor fundamentals. I recommend you check the following articles on Dev.to:

Notes on TypeScript: Fundamentals For Getting Started by A. Sharif

TypeScript Tutorial: A step-by-step guide to learn TypeScript by Educative

Union Types

Union Types reminds of the Or operator, it takes multiple types and only returns the need one. Let's see an example to better understand this.

Sometimes we need a function that takes as a parameter either a number or a string. We can do this with any but c'mon now this is easy, only hardcore situations require any.

Instead, let's use type unions

const complexFunction = (paramter: string | number) => {//code here.};

We can use this with predefined types, let me explain by an example. We may currency type and we only support USD, EUR, and GBP.

type Currency = 'USD' | 'EUR' | 'GBP';

Now any variable that assigned to this type, can be only one of those threes. Thus decreasing the chance of accidentally assigning the wrong value.

Intersection Types

An intersection type combines many types into one. This comes handy when we want to compose existing types into a new one.

Let's say we have an engine type, and color type. We want to create a car type using these types, let's implement this

type Author = {name: string, group:string}

type Admin = {name:string, privilege: string[] }

type User = Author & Admin; //{ name: string, group: string, privilege: string[]}

This is super intuitive, but make sure the similar properties of types have the same type.

type A = {points: string}

type B = {points: number}

type C = A & B //Will throw an error since points properties have different types.

This comes up a lot when working with React. by combining your custom props with element predefined ones.

type Props = {

color: string;

};

const Button: React.FC<Props & React.HTMLAttributes<HTMLButtonElement>> = ({

children,

style,

color,

...props

}) => (

<button style={{ ...style, color }} {...props}>

{children}

</button>

);

// later

<Button color="red" onClick={()=>{}} >Click Here</Button>

Never

Never type is a crazy one, Typescript documentation defined it like this:

The never type represents the type of values that never occur.

From the definition, Never type indicate that a value never occurs, not even undefined.

let's see some examples

const OneFunction = (param):never=> { // Will throw an error, since it returns undefined

console.log(22) // But we said it should never return.

}

const SecondFunction = (param):never => {

while(true){ // Now you see we never returns anything.

}

}

const Third Function = (param):never => {

throw new Error('Shit happens man.')

}

We can notice two patterns from the above example. We should use never type if the function continues to run forever or if it breaks the execution. We can use never to write custom error handlers. Let me know of more use cases, I haven't used never that much.

Type Assertion

With type assertion, we can tell Typescript, yo bro this is the type of this variable you don't need to infer it. Typescript knows that you know better in this situation, so it behaves and does the job.

let a:any= 213 // this is assigned to 'any' type.

let b:number = a as number // using the as keyword, we can assert typescript

// is for sure a number

We can also use type assertion to make a variable immutable.

let a = {name:"alex", age:10}

a.name = "Jhon" // expected behavior

let b = {name:"alex", age:10} as const;

b.name = "jhon" //Typescript compiler will yell at you for mutating it.

Unknown

Unknow is a better solution than any. Unknown typed variables can't be assigned to anything, but we can assign it to other variables.

Unknow is a better solution than any. Unknown typed variables can't be assigned to anything, but we can assign it to other variables.

Okay time for examples

let a:unknown

let b:number = 5

a=b // works.

b=a // Throws an error.

We can handle the unknown type by two ways, narrowing it or with type assertion.

let a:unknown;

let b:number = 5

if(typeof a === 'number'){

b = a // it works

}

b = a as number;// it works too.

Mapped Types

The mapped type takes an existing type and maps its properties to a different type.

const Type<T> = { [P in keyof T]: P }

//Keys //Types

I'd like to read it as for every P (property) in keyof T (Properties of Type T) : give it this type.

The keyof operator indicates that we're looking for all properties of type T.

We can use Mapped types for all magical stuff, we can create a Partial Type, Required Type, and lot more.

type Partial<T> = {

[P in keyof T]?: T[P];

// Keys of T type of each property

};

type Required<T> = {

[P in keyof T]: T[P];

// Keys of T type of each property

// The absense of ? means that every property is required in this Type.

};

type Pick<T, K extends keyof T>= {

[P in K]: T[P]

// P = Properties Selected assigned to generic variable called K

}

// Examples

type User = {

name: string,

email: string,

age?: number

}

let user:User = {name:"Alex", email:"example@test.com"} // Works fine.

let partialUser:Partial<User> = {} // Works fine, since all properties are not required.

let requiredUser: Required<User> = {name: 'Alex'} // throws an error, name and age are required.

requiredUser = {name: "Alex", email: "example@test.com" ,age:12} // Works fine.

let userContactInfo: Pick<User, 'name' | 'email'> = {age:23} // Error. We only picked name and email properties.

userContactInfo = {name:"Alex", email:"example@test.com"}

Typescript has these and other mapped types built-in. Learn more about it in Arthur Vincent Simon's article Typescript Utility Types.

Conditional Types

Conditional type can a bit tricky at first, it's quite difficult to see a use case for it. First, let's see a problem that it fixes.

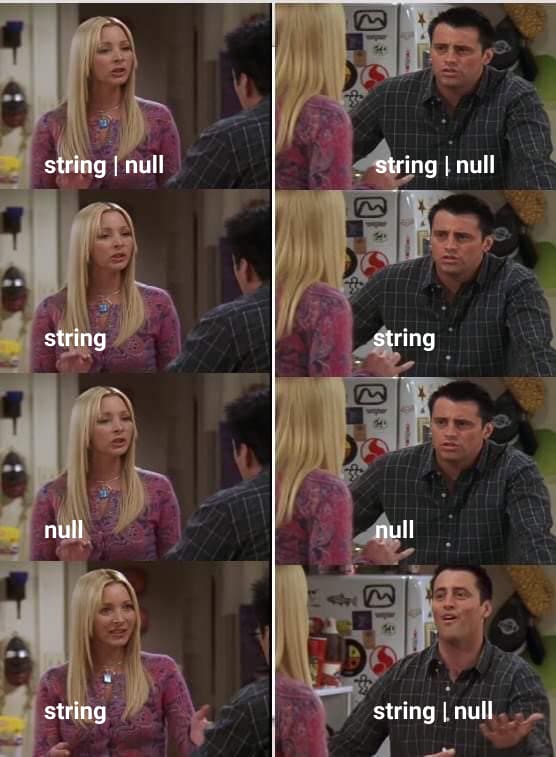

We have a function that takes either a string or null and return string or null. If we pass string we want it to return a string, otherwise null. It seems quite intuitive for Typescript to infer it.

const toLowerCase = (str:string|null):string|null => str ? str.toLowerCase() : null;]

const name = toLowerCase('Alex') // name is a string or null

It was surprising at first this didn't work not gonna lie, maybe the Typescript team should use that GPT 3 thingy. It seems promising.

Anyway, this is a great problem where conditional types shine.

const toLowerCase = <T extends string | null>(

str: T

): T extends string ? string : null => str ? str.toLowerCase() : null;

//Throws an error

//Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'T extends string ? string : null'.

const name = toLowerCase('Alex')

Well sike it didn't work, I know it's disappointing apparently TS can't type-check the return value of functions with conditional return types defined in terms of type parameters.

For this use-case, we can work with function overload.

function toLowerCase(str: null): null;

function toLowerCase(str: string): string;

function toLowerCase(str: string | null): string | null {

return str ? str.toLowerCase() : null;

}

const res = toLowerCase(null) //null

const res = toLowerCase('Alex') //string

Not perfect but it got the job done. I'm looking forward to your opinions about how to deal with this issue.

Tricks I learned in the way.

Type Guards

Type Guards comes handy when you want to narrow a type, you probably already know the typeof operator in Javascript. Its actually used as type guard as well when using Typescript.

const logString = (a: unknown): void =>{

if(typeof a==='string'){

console.log(a) // a is infered as string thanks to the guard we wrote.

}

}

we can also define our custom type guard.

type Car = {

engine: string;

};

const tesla = {

engine: "electric"

};

const isCar = (car: Car): car is Car => {

return typeof car.engine === "string";

};

if (isCar(tesla)) {

console.log(tesla.engine); // 'electric' and tesla is a car in this block.

}

Derive Types from Constants

I'm stealing this idea from this awesome talk. By defining a const variable, we can derive types from it. We have an Icon system, we can easily derive its type thus decreasing the overload of updating the type each type a new icon is added

const Icons = {

twitter: ()=>//..,

github: ()=>//..

devto: ()=>//..

} as const

type Icon = keyof typeof Icons // "twitter" | "github" | "devto";

Using comments with Types

I always pray for developers when they provide a definition of what an argument or property is intended to do. A comment per type makes me jump from hype. It also removes the factor of assumptions.

type Car = {

/** It powers the car. */

engine: string,

/** Timer for self-destruction. Starts during launch. */

selfDesruct:number

}

const getCar = (car:Car)=>{}

Where do I find Types for Third party libraries

Usually libraries have Typescript support, but if not, google your library + @types and hopefully you'll find it.

You can follow me on twitter @AmineJv ( I'll start tweeting soon, it's about time till I rise from the ashes.)

Top comments (9)

And then you suddenly realize that you can can put TypeScript types in JSDoc as well, that is

*.js. (and interfaces are possible with@typedef)But it cannot really replace everything. TypeScript is a lock-in game.

Personally I haven't worked with JSDoc, but it seems interesting I will give it try.

There's an error in "Unknown" type section. It should be

if (typeof a === "number") {b = a

}

Thank you, I fixed it

Excellent refresher on some Typescript features Amine.

I don't use .ts files, but I get near all the services of TS with JSDocs, while allowing the code to remain pure JavaScript.

TS also willl not give runtime checks, as it downpiles to untyped JS.

To use your lowercase example above, to enforce runtime checks (where the productions bugs are found), I use this idiom....

Compile time checks are always better than runtime checks. Interesting obsession. Given that argument would be typed, the only way it could fail is if you lied to the compiler at some point. Typically that might be the point of deserialization... Test your inputs in one place and then trust your compiler. Also, types show intent. JSDoc isn't a type checker (or is it?)

Super useful post. Thanks. 👍

Perfectly illustrates why TypeScript is a crutch for developers coming from strongly typed languages

Cool resume! It will enrich my cheat sheet!