This post shares lessons I’ve learned during my experience as dev team lead for software agencies. My goal is to make other team leads feel more confident in their roles, and to encourage developers who are considering stepping into this position to go ahead and make the leap.

My Experience

I’ve been leading software development teams as Sitecore architect and dev lead for over 3 years. My last team had 9 back-end .NET/Sitecore developers and 2 front-end developers. We were spread out across the globe - the earliest start to the day was GMT+2, and the latest GMT-8. Working in a large, remote team was challenging, but we hit a very ambitious deadline for an enterprise client, which resulted in approval of a big roadmap of follow-up work.

On a typical project, I was expected to review business requirements, write technical requirements, choose technologies and frameworks, provide estimates, steer implementation, review code and give feedback, write documentation, onboard and mentor developers, decide which developers do which work, keep the Project Manager informed on the progress of everyone’s work, manage deployments, consult the client on the direction and strategy of future work, attend (many) meetings, and, oh yea… write code.

We were always working towards a deadline, so it was important that all work streams progress as planned. If something was significantly impeding our progress, whether it was an internal resourcing issue or an external blocker, I needed to step in and help resolve it to keep things moving.

Aside from leading teams myself, I’ve also been a member of teams under other leads, some technical and some non-technical.

Part 1 - Internal Skills

This section is about shaping your personality and behavior to set yourself up to be a great leader - increasing confidence, being aware of feedback, seeking out resources to learn more about leadership, etc.

You are not an imposter

I will admit that although my team was very successful, every now and then that sneaky imposter syndrome came out and kicked me. That’s because I, like many other people with my title, got promoted to my leadership position because I was a competent, self-sufficient developer, a fast learner, and I was good at communicating technical concepts. I have a Computer Science degree, but I never received any formal training on how to manage or lead people. That’s something I’ve just had to figure out as I go.

As you may have noticed from the “My Experience” section above, most of the things I did as team lead involved managing work streams and engaging in verbal or written communication with my team. Whereas writing code - the thing that got me promoted and the thing I know I’m good at - is what I do the least. Hence the imposter syndrome.

If you are a developer who’s taken on the role of team lead and you find yourself feeling like an imposter - meaning you question whether you’re qualified to manage people and you worry whether you’re doing it right, - let me assure you that you are not an imposter. Generally, teams perform better with a lead who’s a seasoned developer who is learning how to manage than with a lead who has management experience, but doesn’t understand what the developers are doing.

So my advice is to shush those nagging inner attacks on your qualifications. Remind yourself that the people who promoted you knew what they were doing, and they must have known you’re capable of growing into a leader, even if you lack the experience. Which brings me to the next section…

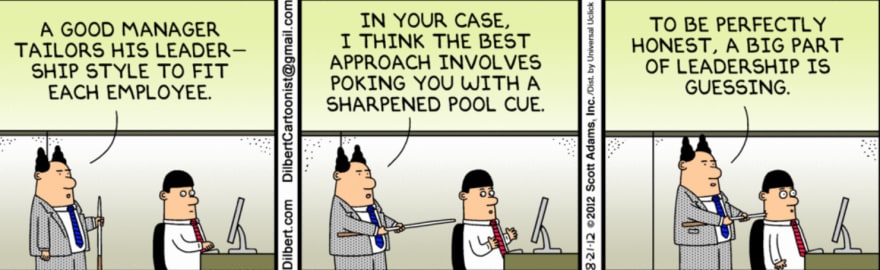

Leadership is a learned skill

No one is born with the talent to lead. All the great leaders in your life who make it look easy started out like you and improved over time. Improvement happens from consciously taking notice of behaviors that motivate people and increase performance, then practicing these behaviors. If you don’t think you’re a strong leader, but you are in a leadership role, don’t worry. You can improve, and you can practice the specific communication skills that are so crucial to being a good leader.

The ideal way to learn is through a mentor, either in your company or even in your family. Most leadership skills are industry-agnostic, so it’s ok if your mentor is not a developer. If there are no mentors available to you, or you think that weekly meetings with a mentor won’t be enough, then the next best thing is to look up the topic on Amazon and order some books. Ask your colleagues for recommendations (Brené Brown’s Dare To Lead is fantastic).

Decide who to accept feedback from…

One thing I can say for certain about being dev lead is that there was never a lack of critique and opinions from those who didn’t have skin in the game like I did. As the face of the team, I was first in the line of fire for all kinds of feedback, both constructive and condescending.

My advice is to get clear on whose opinions matter. It’s impossible to please everyone. You’re the one who has to stand behind the implementation, and your obligations are to your team, your boss, and your business stakeholders. Beyond that, treat feedback as suggestions. This will minimize stress and confusion from all the (sometimes conflicting) comments and requests flying your way.

…then be open to the feedback

Once you decide whose opinions you value, make a conscious effort to make yourself open to the feedback.

First, these people might not know that you want their opinions, so you may need to ask for it. Second, not everyone is good at giving feedback. For example, I knew a very smart developer who was very bad at writing pull request comments. The way he challenged my team’s code was snarky, and sometimes even rude. Although his delivery certainly could have been better, he made good suggestions that benefited the project.

My advice is to strip feedback down to facts in your mind so you can understand the message without the emotion and attitude of the messenger. Then it will be easier to determine if the feedback needs to be acted on.

To be clear, I’m not saying that you should tolerate people acting like jerks, which brings me to the next section…

Be brave

As team lead, you have the power to set the tone for what kind of attitudes are acceptable at meetings. Be brave enough to stand up for your team and your implementation if either are being talked down. The most important thing is for the people who report to you to know that you have their backs. You also have the power to set the bar for how hard your team is pushed. Be brave enough to defend estimates and point out scope creep.

Part 2 - External Skills

This section is about the interpersonal skills that need to be practiced to improve the quality of your interaction with your team and the effectiveness of your leadership - mentoring, communication, strengthening team bonds, etc.

Mentoring is a priority

If coding is the smallest part of the job, then what happens to all those wonderful developer skills that got your promoted? The answer is that you multiply them by spreading them to your team. One of your top responsibilities as team lead is to mentor your developers - that is the biggest value that you provide to your company.

My advice for mentoring is:

- Get to know your developers’ strengths and weaknesses, and assign work based on skill level and growth goals. Assign work that’s challenging, but doesn’t make someone feel “in over their head”. Set team members up for success, to make them feel like they can do anything. To gauge whether developers are succeeding in their tasks, have regular one-on-one touch bases (aim for daily). “How are things going?”

- Don’t wait for devs to come to you. Instead, check in with your devs regularly to inquire about their progress and show that you are available for discussions. A friendly “Hey, how are you doing on such-and-such? Do you have any questions?” is a great way to check in casually without making it feel micro-managy.

- At least once per sprint, have a knowledge-sharing meetings just for the developers where everyone discusses the work they did, and the challenges they faced.

- Write as much documentation as possible. The goal of mentoring is spreading knowledge, and documentation is a collaborative way to share knowledge that continues to live on even after you move on to a different project.

Utilize the entire team for consulting

I used to hold this unrealistic expectation that I need to be an expert in all subjects that my team is working with. This came from good intentions - I simply wanted to be able to answer all questions myself to avoid pulling extra people into meetings so the team could be heads down in work. Also, since my team often discussed implementation strategy with me, I liked going into conversations already having knowledge about the context. The reality is that this mindset caused a ton of extra stress for me since I constantly had to do research and extra prep for meetings. And more importantly, it denied my team members the chance to practice explaining technical topics, which is a crucial skill.

So my advice is to keep up with the knowledge across your work streams as much as you can, but recognize that your team is packed with Subject Matter Experts and utilize them all as much as possible. Try to have at least one dev with you at every technical meeting. You may need to argue the case for this to the Project Manager, since now the number of devs in meetings will double, so make it clear that it’s an investment into the growth of the team. “Sharing” the meetings has an added benefit in that it prevents all the knowledge from being stashed with one person. So if you ever leave the project, it won’t be as big of a hit to the team.

Know when to listen rather than problem-solve

One issue I continuously faced as lead was that when devs came to me with a problem, I immediately jumped into “how would I solve this myself” mode. This, too, came from good intentions. I wanted to be helpful, and I wanted to get people unblocked so they could progress in the sprint. It was also a matter of me getting excited about working on a coding challenge since I didn’t get to code as often. I had to keep reminding myself that being patient and giving people the chance to figure it out on their own was the best thing for the team.

My advice is to ask people to be more explicit about what they need from you. For example, “Anastasiya, can I bounce some ideas off you about such-and-such?” vs “Anastasiya, I’ve spent a long time on such-and-such, but it’s still not right. I need your help.” When the request is worded so explicitly, there is no doubt in my mind about whether I need to offer solutions or just shut up and listen. If the request you receive is worded vaguely, simply ask, “How can I help?” to get clarity on the intent.

As lead, you are responsible for ensuring that the team is aligned on implementation goals, and any technical constraints that need to be followed. But give the developers the freedom to make decisions about implementation details themselves. Tell the team what to build, not how to build it.

Remember that mistakes are ok

When you allow the team freedom to make decisions about implementation details, they will try things that sometimes don’t work out. Never shame someone for trying something that needs to be refactored later, this is how we all learn.

If you suspect that someone is heading down a bad path during one of your implementation check-ins, its tempting to just call out the issue, “O no you shouldn’t do it like that, do such-and-such instead.” Granted, you’re not trying to be mean in this situation, you’re just trying to save the dev from future time wasted on troubleshooting. And sure, if it’s a critical error that’s going to take down the server then go ahead and point it out, but that’s rarely the case. Usually it’s a matter of an edge-case getting overlooked or something like that. In this case, my advice is to lead the developer in a conversation that gets him or her thinking about the issues, and leaves the actual problem-solving to him or her. For example, “Have you thought about what would happen if a user tries to interact with this component with only a keyboard?” or “Do you think this component has any security vulnerabilities?” Teach people how to seek out the information they need without directly telling them that they are doing wrong.

Always assume positive intent.

I saw a tweet recently that perfectly summarized this notion:

Everyone on the team is always doing their best to get the job done based on the information that have at the time. They are working against constraints and challenges which may not be obvious when their work is reviewed later on.

This is probably the single most important piece of advice on this page. It will go a long way in both, reducing how much stress and frustration you feel at work, and improving the perception that other’s have of you.

Praise people for doing good work.

Especially in front of others. Tell your boss about the good work that your people are doing. Remember to give praise across departments too.

Don’t jump to assumptions

For me, leading people blurred into managing people whenever a developer fell short of agreed-upon expectations such as satisfying sprint commitments, being available online (for remote workers), or adhering to the pull request checklist.

If you are in the position of having to confront a developer about his/her performance, my advice is to avoid making assumptions and simply ask for an explanation during one of your regular check-ins. The developer probably just encountered issues that you were not aware of, and it won’t become a repeating issue.

But if you do find yourself struggling over the same issues with a developer time and time again, and you need to have a more formal meeting, then my advice is to explain the ramifications on the rest of the team. Don’t make threats or tell the person how to solve the problem. Ask him/her to come up with a solution, “What are you going to do to make sure you don’t have another week like this?” Get the team member to commit to a solution and document it. Then have a follow up meeting a couple of weeks later to determine if the person followed through.

Be human

I’m not perfect at leading or managing. Sometimes I say the wrong thing, sometimes I get emotional, sometimes I offend people. All the things on this page that I say not to do - I’ve done all of them, that’s how I know it’s best to try to avoid them. When I mess up, it happens in front of the team or the client, so I am not a stranger to feeling embarrassed.

My final piece of advice is to get comfortable with feeling uncomfortable. Admit when you’ve made a mistake, learn from it, apologize if necessary. Then forgive yourself and move forward.

Bon Appétit!

Top comments (4)

This post is amazing. I made sure to fully sit down and read it.

The last month or so I've been doing those "implementation" meetings with just the developer every 1-2 weeks and I must say I've noticed a huge difference in how the team preforms. It was something I just kind of thought about doing thinking and what I would like. Glad to read about it here.

Wow, this is for sure one of the most interesting articles I've came across with lately! 👏👏👏

Thank you for sharing your experience!

I loved this article! Thanks for sharing your experience.

I'm currently working as a team lead (I'm pretty new to this) and I can totally relate with many things.

Part "You are not an imposter" looks like story of my life ;)