Copy-On-Write, abbreviately referred to as CoW suggests deferring the copy process until the first modification. A resource is usually copied when we do not want the changes made in the either to be visible to the other. A resource here could be anything - an in-memory page, a database disk block, an item in a structure, or even the entire data structure.

CoW suggests that we first copy by reference and let both instances share the same resource and just before the first modification we clone the original resource and then apply the updates.

Deep copying

The process of creating a pure clone of the resource is called Deep Copying and it copies not only the immediate content but also all the remote resources that are referenced within it. Thus if we were to deep copy a Linked List we do not just copy the head pointer, rather we clone all the nodes of the list and create an entirely new list from the original one. A C++ function for deep copying a Linked List is as illustrated below

struct node* copy(struct node *head) {

if (!head) {

return NULL;

}

struct node *nhead = (struct node *) calloc(sizeof(struct node))

nhead->val = head->val;

struct node *p = head;

struct node *q = nhead;

while(p -> next) {

q -> next = (struct node *) calloc(sizeof(struct node));

q -> next -> val = p -> next -> val;

p = p -> next;

q = q -> next;

}

return nhead;

}

Going by the details, we understand that deep copying is a very memory-intensive operation, and hence we try to not do it very often.

Why Copy-on-Write

Copy-on-Write, as established earlier, suggests we defer the copy operation until the first modification is requested. The approach suits the best when the traversal and access operations vastly outnumber the mutations. CoW has a number of advantages, some of them are

Perceived performance gain

By having a CoW, the process need not wait for the deep copy to happen, instead, it could directly proceed by just doing a copy-by-reference, where the resource is shared between the two, which is much faster than a deep copy and thus gaining a performance boost. Although we cannot totally get rid of deep copy because once some modification is requested the deep copy has to be triggered.

A particular example where we gain a significant performance boost is during the fork system call.

fork system call creates a child process that is a spitting copy of its parent. During this call, if the parent's program space is huge and we trigger a deep copy, the time taken to create the child process will shoot up. But if we just do copy-by-reference the child process could be spun super fast. Once the child decides to make some modifications to its program space, then we trigger the deep copy.

Better resource management

CoW gives us an optimistic way to manage memory. One peculiar property that CoW exploits are how, before any modifications to the copied instance, both the original and the copied resources are exactly the same. The readers, thus, cannot distinguish if they are reading from the original resource or the copied one.

Things change when the first modification is made to the copied instance and that's where readers of the corresponding resource would expect to see things differently. But what if the copied instance is never modified?

Since there are no modifications, in CoW, the deep copy would never happen and hence the only operation that ever happened was a super-fast copy-by-reference of the original resource; and thus we just saved an expensive deep copy operation.

One very common pattern in OS is called fork-exec in which a child process is forked as a spitting copy of its parent but it immediately executes another program, using exec family of functions, replacing its entire program space. Since the child does not intend to modify its program space ever, inherited from the parent, and just wants to replace it with the new program, deep copy plays no part and is a waste. So if we defer the deep copy operation until modification, the deep copy would never happen and we thus save a bunch of memory and CPU cycles.

#include <stdio.h>

int main( void ) {

char * argv[2] = {".", NULL};

// fork spins the child process and both child and the parent

// continues to co-exist from this point with the same

// program space.

int pid = fork();

if ( pid == 0 ) {

// The entire child program space is replace by the

// execvp function call.

// The child continues to execute the `ls` command.

execvp("ls", argv);

}

// Child process will never reach here.

// hence all memory that was copied from its parent's

// program space is of no use.

// The parent will continue its execution and print the

// following message.

printf("parent finishes...\n");

return 0;

}

Updating without locks

Locks are required when we have in-place updates. Multiple writers try to modify the same instance of the resource and hence we need to define a critical section where the updations happen. This critical section is bounded by locks and any writer who wishes to modify would have to acquire the lock. This streamlines the writers and ensures only one writer could enter the critical section at any point in time, creating a chokepoint.

If we follow CoW aggressively, which suggests we copy before we write, there will be no in-place updates. All variables during every single write will create a clone, apply updates to it and then in one atomic compare-and-swap operation switch and start pointing to this newer version; thus eradicating the need for locking entirely. Garbage collection on unused items, with old values, could happen from time to time.

Versioning and point in time snapshots

If we aggressively follow CoW then on every write we create a clone of the original resource and apply updates to it. If we do not garbage collect the older unused instances, what we get is the history of the resource that shows us how it has been changing with time (every write operation).

Each update creates a new version of the resource and thus we get resource versioning; enabling us to take point-in-time snapshots. This particular behavior is used by all collaborative document tools, like Google Docs, to provide document versioning. Point-in-time snapshots are also used in the databases to take timely backups allowing us to have a rollback and recovery plan in case of some data loss or worse a database failure.

Implementing CoW

CoW is just a technique and it tells us what and not how. The implementation is all in the hands of the system and depending on the type of resource being CoW'ed the implementation details differ.

The naive way to perform copy operation is by doing a deep copy which, as established before, is a super inefficient way. We can do a lot better than this by understanding the nuances of the underlying resource. To gain a deeper understanding we see how efficiently we could make CoW Binary Tree Binary Tree.

Efficient Copy-on-write on a Binary Tree

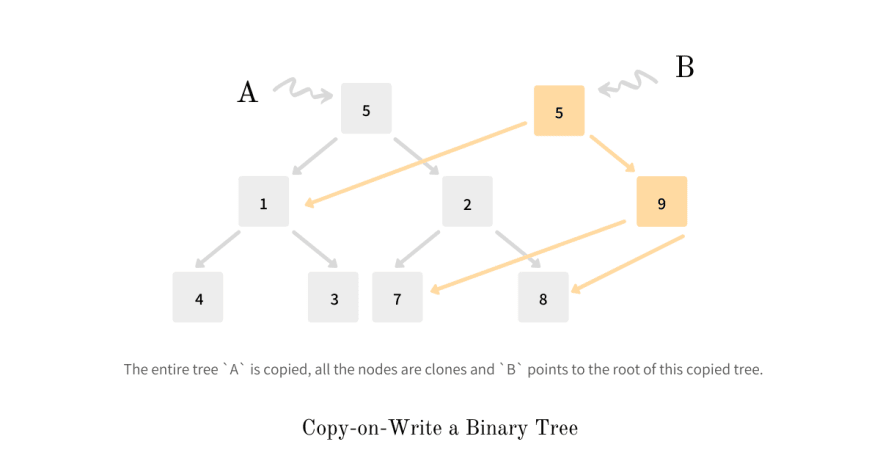

Given a Binary Tree A we create a copy B such that any modifications by A are not visible to B and any modifications on B are not visible to A. The simplest way to achieve this is by cloning all the nodes of the tree, their pointer references, and create a second tree which is then pointed by B - as illustrated in the diagram below. Any modifications made to either tree will not be visible to the other because their entire space is mutually exclusive.

Copy-on-Write semantics suggest an optimistic approach where B instead of pointing to the cloned A, shares the same reference as A which means it also points to the exact same tree as A. Now say, we modify the node 2 in tree B and change its value to 9.

Observing closely we find that a lot of pointers could be reused and hence a better approach would be to only copy the path from the updating node till the root, keeping all other pointers references same, and let B point to this new root, as shown in the illustration.

Thus instead of maintaining two separate mutually exclusive trees, we make space partially exclusive depending on which node is updated and in the process make things efficient with respect to memory and time. This behavior is core to a family of data structures called Persistent Data Structures.

Fun fact: You can model Time Travel using Copy-on-Write semantics.

Why shouldn't we Copy-on-Write

CoW is an expensive process if done aggressively. If on every single write, we create a copy then in a system that is write-heavy, things could go out of hand very soon. A lot of CPU cycles will be occupied for doing garbage collections and thus stalling the core processes. Picking which battles to win is important while choosing something as critical as Copy-on-Write.

References

Other articles you might like:

- What makes MySQL LRU cache scan resistant

- Building Finite State Machines with Python Coroutines

- Solving an age-old problem using Bayesian Average

- Pseudorandom numbers using Cellular Automata - Rule 30

- Overload Functions in Python

This article was originally published on my blog - Copy-on-Write Semantics.

If you liked what you read, subscribe to my newsletter and get the post delivered directly to your inbox and give me a shout-out @arpit_bhayani.

Top comments (0)