Encrypted Media Extensions (EMEs) are a hotly debated, recently added extension to the HTML5 specification. They are meant to provide support for Digital Rights Management (DRM) for media played in the browser.

Large companies with deep pockets stand to benefit from the implementation and adoption of EMEs. As soon as EMEs were introduced by the W3C, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) resigned from the W3C group with an open letter. The Free Software Foundation (FSF) also called for the W3C group to reject the EME proposal.

On the other hand, all of the major browsers have rolled out support for the EME spec and have been put into use by content providers like Netflix.

Why are EMEs such a controversional concept? To answer this question, we need to dig into the motivation behind the technology.

Motivation

When media (e.g. music or movies) were recorded on analog mediums (e.g. tapes), there was a built-in limit to the amount of sharing that could take place. Copying a tape meant a loss of quality, so creating a copy of a copy of a copy made the original content basically unusable. This meant that artists could safely release their work without too much worry about everyone getting a copy of it for free.

Then, we switched to digital copies of content which meant lossless copies could be created easily. That’s when the concept of Digital Rights Management (DRM) software hit the scene.

DRM allows publishers to control how consumers can view their content. There are a number of different DRM schemes, but each has the same basic structure: the publisher encrypts the content with a key that the publisher later hands over to the user for a limited amount of time. Of course, there are large chunks of details we’re leaving out. Grasping the basic idea is enough for the time being.

DRM has pretty much always been controversial. The Free Software Foundation suggests that since DRM prevents what you can do with the content that you’ve purchased (e.g. you can’t copy it arbitrarily), it “creates a damaged good; it prevents you from doing what would be possible without it.” It certainly didn’t help that Sony BMG once installed rootkits on customer’s computers without user permission in order to enforce DRM.

Most of the DRM tech we’ve discussed so far was developed in the era when people still bought DVDs/CDs and consumed content on machines using desktop software. Both of these are, essentially, behaviors of the past.

We consume movies and music through services like Netflix, Spotify, Pandora, Apple Music, etc., often over the web. Netflix, et al. are obligated, due to agreements with content partners, to serve their content with DRM. Moreover, web streaming is likely a significant chunk of usage for Netflix. This makes the problem of enforcing DRM over the web an incredibly important problem for Netflix, et al. to solve.

That’s where EMEs come into play. They are essentially a technology that allows the browser to communicate with DRM systems over an encrypted medium. They make it possible for DRM software to work over the browser and relay encrypted content to the user. This means Netflix can serve you a movie that’s encrypted and protected by DRM.

The tech

The tech behind EMEs is particularly interesting and is part of the controversy surrounding the standard.

Say Felix is a movie streaming service that serves up movies over the browser and uses EMEs to protect the content it delivers. Suppose that user wants to play some encrypted content from Felix. Here’s what happens:

- The browser will load up this content, realize it is encrypted and then trigger some Javascript code.

- This Javascript will take the encrypted content and pass it along to something called the Content Decryption Module (CDM) — more on this later.

- The CDM will then trigger a request that will be relayed by Felix to the license server. This is a Felix-controlled server that determines whether or not a particular user is allowed to play a particular piece of content. If the license server thinks our user can watch the content, it will send back a decryption key for the content to the CDM.

- The CDM will then decrypt the content and it will begin playing for the user.

The most important chunk of this whole process is the CDM. By its nature, the CDM has to be a piece of code that’s trusted by Felix. If it isn’t, Felix can’t be sure that it will do what it wants it to. This means that the CDM has to come with the browser. There are a couple of different providers for CDMs, including Google’s Widevine and Adobe Primetime. Both of these provide the encryption support necessary for content providers such as Felix to enforce DRM.

Controversy

There are multiple pieces to the story behind the fight over EMEs. First, there is an inherent opposition to DRM that parties like the Free Software Foundation have voiced. They argue that introducing DRM on the web will dramatically reduce the freedoms of the consumers to use their devices as they want.

Moreover, DRM also prevents the legitimate alteration of content, like adding subtitles to video. This means that legitimate software that improves the accessibility of the web will be adversely impacted by the introduction of EMEs.

There are no protections within DRM for security researchers: if you tamper with DRM, you are generally considered a wrongdoer, even if you are doing it for research purposes.

The camp of people set against DRM has been around for quite a while — EMEs are another front in their battle against DRM, one that’s particularly important given that the web has become the dominant form of content distribution. This opposition is not to be taken lightly. Tim Wu, one of the leaders behind the net neutrality movement, stands against EMEs for these reasons. The Ethereum Foundation has also spoken out against the implementation of EMEs as a standard.

Content Decryption Module

But, there’s another angle to the fight against EMEs that revolves around CDMs. As they are currently implemented, CDMs are essentially closed-source binary blobs that come with your browser.

This implies that EMEs lead to the introduction of closed source software within the browser. Since browsers constitute such a crucial part of the software ecosystem, open source implementations are arguably very important for security, consumer protections, etc.

Moreover, lack of access to closed source CDM implementations may lead to a lack of competitiveness in the browser space. In the past, there have been similar debates around closed source codecs and their place within Linux. Arguably, however, the role of closed source software in the traditionally open web is more significant.

What will happen vs what should happen

Now that we’ve considered the status of the debate, I’ll step into the arena. There are two important questions here: what will happen and what should happen. The former is easier to answer; the latter is more subjective.

There are tremendous economic incentives that point in the direction of EME adoption. As I mentioned, actors with deep pockets are committed to making them a core part of the web. Also, EMEs work pretty well from a technical standpoint for the majority of internet users, leaving little incentive for content providers to refuse to use EMEs.

As the affirmation of EMEs by W3C suggests, the tide is in favor of the standard and will be for a significant amount of time. To counteract this movement, users must be convinced that the harms of EMEs are significant enough to select providers that don’t use them. I don’t see any evidence of this being the case for the average user at the moment.

This means I believe the web is heading toward greater proliferation of DRM, not less.

Now, to the more difficult question: what should happen. I have some clear beliefs, e.g. security researchers should be granted exemption from the penalties associated with violating DRM; there should be open source implementations of CDMs that the community can rely on, etc.

On other issues, I am not so sure. It makes sense to me that content providers should be able to protect the content they spend millions of dollars to produce. But, the implications of this (reduced accessibility on the web, fewer consumer rights) also scare me. Moreover, I am certain that introducing DRM over audio/video media elements will gradually lead to DRM over more content.

Holding these beliefs simultaneously is kind of a cop-out because there doesn’t seem to be a solution that satisfies for all of them, for now. Maybe things will change as smart people work on this problem.

Plug: LogRocket, a DVR for web apps

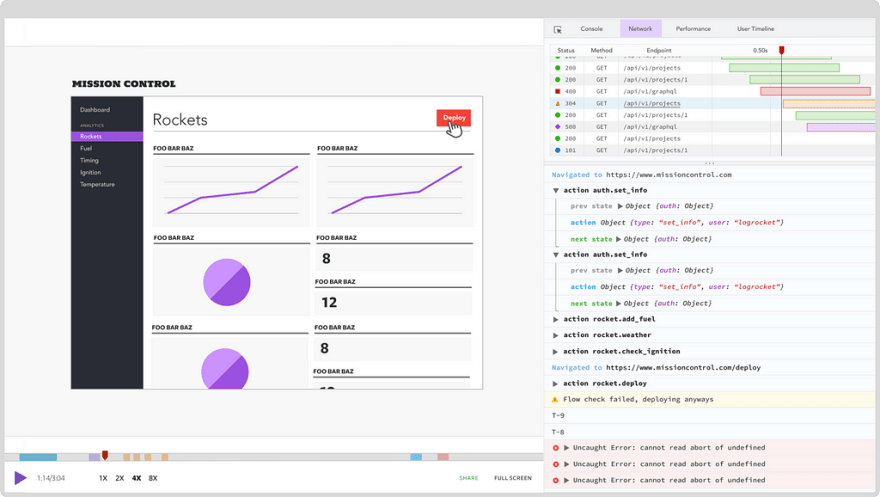

LogRocket is a frontend logging tool that lets you replay problems as if they happened in your own browser. Instead of guessing why errors happen, or asking users for screenshots and log dumps, LogRocket lets you replay the session to quickly understand what went wrong. It works perfectly with any app, regardless of framework, and has plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

In addition to logging Redux actions and state, LogRocket records console logs, JavaScript errors, stacktraces, network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. It also instruments the DOM to record the HTML and CSS on the page, recreating pixel-perfect videos of even the most complex single page apps.

Top comments (0)