In the last blog post of this series, I shared a look behind the IQueryable curtain. Using a special “query host,” I demonstrated how to iterate the expression tree, and even modify it, so the query executes differently. The problem is that the approach is limited because inspection/modification only works when you are in control of the end-to-end query. You lose control and insights when the query is handed off, extended, and/or run again. How do products like EF Core allow you to write whatever queries you like, then successfully intercept them to run SQL commands? The secret is in the provider.

To help explain these concepts, I built an example project that you can browse and download here:

JeremyLikness

/

QueryEvaluationInterceptor

JeremyLikness

/

QueryEvaluationInterceptor

An example of intercepting IQueryable executions to parse and transform the query.

QueryEvaluationInterceptor

An example of intercepting IQueryable executions to parse and transform the query.

The “query host” is really just an implementation of IQueryable. The basic properties on the interface include:

- The

ElementTypethe query is for - The

Expressionthat represents the definition/structure of the query - The

Providerto implement the expression and materialize the results

Think of the query host as the container that queries are built against. This is the definition. The IQueryProvider is the implementation. This should be evident by the main methods on the interface:

-

CreateQuerythat is responsible for producing theIQueryablethe expression represents. -

Executethat is responsible for running the query.

As long as you are defining filters, projections, sorts, and other parts of a query (for inspiration, you can take a look at the various Queryable methods) you are working with the host. The instant you start to iterate the results of a query, the provider comes into play. For default “LINQ to Objects” this involves sorting and filtering objects in memory. For EF Core, this involves generating the database statements that make sense for the provider being used, such as SQL.

The general flow looks like this:

- Build the query: apply extension methods against the

IQueryablehost - Execute the query, i.e. begin to iterate or call

ToList()- To provide the results,

GetEnumerator()is called on the query host - This results in a call to

CreateQuery()on the provider - Ultimately, the expression tree is executed to return the results

- To provide the results,

- Any time a new type is encountered (i.e. when you have a subquery, or project results to an anonymous type), another call to

CreateQueryis made using the new type.

The Provider

I’m not ready to build a full provider yet. Instead, I created a hybrid provider that intercepts the process to provide a hook to inspect and/or mutate the expression tree. It then passes the modified expression to the original provider. This allows it to work equally well with built-in providers like LINQ to Objects and external ones like EF Core. The interface for the basic provider looks like this:

public interface ICustomQueryProvider<T> : IQueryProvider

{

IEnumerable<T> ExecuteEnumerable(Expression expression);

}

This is just a custom method for the host to call with the expression. This is where the interception will happen.

An abstract base class takes care of the default implementation:

public abstract class CustomQueryProvider<T> : ICustomQueryProvider<T>

{

public CustomQueryProvider(IQueryable sourceQuery)

{

Source = sourceQuery;

}

protected IQueryable Source { get; }

public abstract IQueryable CreateQuery(Expression expression);

public abstract IQueryable<TElement> CreateQuery<TElement>(Expression expression);

public virtual object Execute(Expression expression)

{

return Source.Provider.Execute(expression);

}

public virtual TResult Execute<TResult>(Expression expression)

{

object result = (this as IQueryProvider).Execute(expression);

return (TResult)result;

}

public virtual IEnumerable<T> ExecuteEnumerable(Expression expression)

{

return Source.Provider.CreateQuery<T>(expression);

}

}

There are two key features of the custom provider: it captures the original query (therefore the original provider), and when the “execute” methods are called, it passes the expression to the original provider.

The query host and provider go hand in hand. Here is the definition of a QueryHost that is ready to use the new provider (yet to be defined):

public class QueryHost<T> : IQueryHost<T, IQueryInterceptingProvider<T>>

{

public QueryHost(

IQueryable<T> source)

{

Expression = source.Expression;

CustomProvider = new QueryInterceptingProvider<T>(source);

}

public QueryHost(

Expression expression,

QueryInterceptingProvider<T> provider)

{

Expression = expression;

CustomProvider = provider;

}

public virtual Type ElementType => typeof(T);

public virtual Expression Expression { get; }

public IQueryProvider Provider => CustomProvider;

public IQueryInterceptingProvider<T> CustomProvider { get; protected set; }

public virtual IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator() =>

CustomProvider.ExecuteEnumerable(Expression).GetEnumerator();

}

The key features to note are the capture of the custom provider in the constructor calls, and the implementation of GetEnumerator that passes the request to the custom provider. What does the custom provider look like?

The Expression Transformer

To intercept and modify the query requires a function that takes in the original expression and returns the mutated one. Here is the definition of the transformation:

public delegate Expression ExpressionTransformer(Expression source);

The provider needs to be aware of the transformation. Here is an interface that defines how to register it:

public interface IQueryInterceptor

{

void RegisterInterceptor(ExpressionTransformer transformation);

}

Now onto the intercepting provider…

The Query Interception Provider

This is the code for the intercepting provider:

public class QueryInterceptingProvider<T> :

CustomQueryProvider<T>, IQueryInterceptingProvider<T>

{

private ExpressionTransformer transformation = null;

public QueryInterceptingProvider(IQueryable sourceQuery)

: base(sourceQuery)

{

}

public override IQueryable CreateQuery(Expression expression)

{

return new QueryHost<T>(expression, this);

}

public override IQueryable<TElement> CreateQuery<TElement>(Expression expression)

{

if (typeof(TElement) == typeof(T))

{

return CreateQuery(expression) as IQueryable<TElement>;

}

var childProvider = new QueryInterceptingProvider<TElement>(Source);

return new QueryHost<TElement>(

expression, childProvider);

}

public void RegisterInterceptor(ExpressionTransformer transformation)

{

if (this.transformation != null)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException();

}

this.transformation = transformation;

}

public override object Execute(Expression expression)

{

return Source.Provider.Execute(TransformExpression(expression));

}

public override IEnumerable<T> ExecuteEnumerable(Expression expression)

{

return base.ExecuteEnumerable(TransformExpression(expression));

}

private Expression TransformExpression(Expression source) =>

transformation == null ? source :

transformation(source);

}

So, what’s going on? In a nutshell, the custom provider does three things.

- When

CreateQueryis called, it ensures that the new query also uses the custom provider. If it is the same type, it uses the same instance of provider, otherwise it creates a new one. - It implements the interface to register a transformation an stores it as a property. It ensures the transformation is only registered once.

- When the execute methods are called, it transforms the expression before passing them to the source provider.

That’s it! The query host uses the custom provider. The custom provider ensures any new query hosts that are created also use the custom provider. It also transforms the expression before passing it to the original provider.

A Query Snapshot

The basic building blocks are in place and we are ready to test the implementation. I’m using a Thing that generates random properties and half-truths to create a nice spread to query against.

public class Thing

{

private static readonly Random Random = new Random();

public string Id { get; private set; } = Guid.NewGuid().ToString();

public int Value { get; private set; } = Random.Next(int.MinValue, int.MaxValue);

public DateTime Created { get; private set; } = DateTime.Now;

public DateTime Expires { get; private set; } = DateTime.Now.AddDays(Random.Next(1, 999));

public bool IsTrue { get; private set; } = Random.NextDouble() < 0.5;

}

A static method generates 10,000 things. Next, I set up the interceptor. The first interception doesn’t change the expression. It just writes it to the console (the default ToString() override provides a very clear representation of the entire expression tree).

static Expression ExpressionTransformer(Expression e)

{

Console.WriteLine(e);

return e;

}

Next, the API sets up the query for consumption. It wraps it in the query host and registers the “transformation”. The query is now ready for consumption.

var query = new QueryHost<Thing>(ThingDbQuery);

query.CustomProvider.RegisterInterceptor(ExpressionTransformer);

The consumer is simply presented with an IQueryable<Thing> to build queries against (this is what is implemented by QueryHost.)

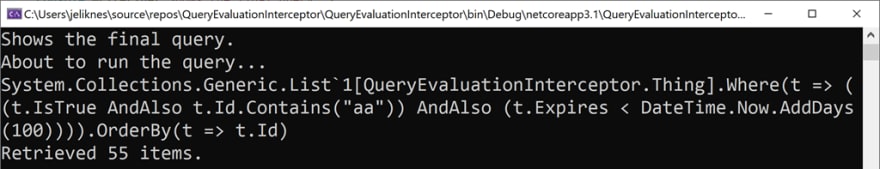

Here is a query that is immediately parsed to a list:

var list = query.Where(t => t.IsTrue &&

t.Id.Contains("aa") &&

t.Expires < DateTime.Now.AddDays(100))

.OrderBy(t => t.Id).ToList();

Console.WriteLine($"Retrieved {list.Count()} items.");

Running this results in the following output:

If you step through in debug mode, you’ll see that the provider is called and immediately “transforms” the expression, resulting in the output to the console. That’s it for an interception. Next, how about a mutation?

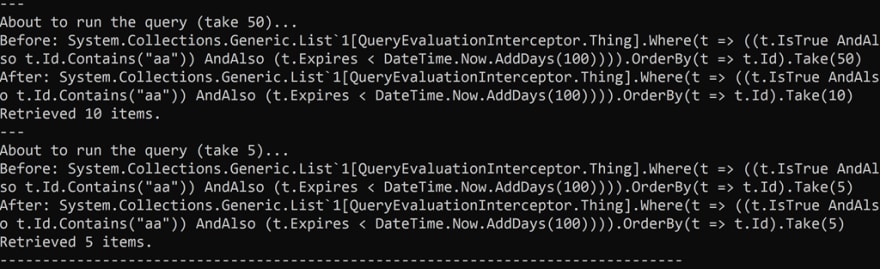

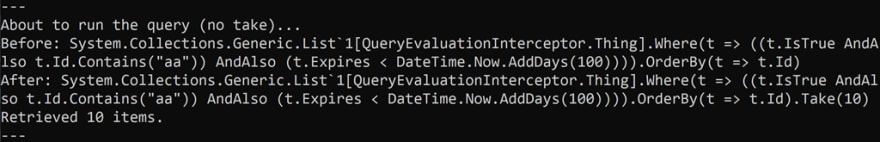

Query “Guard Rails”

One challenge with exposing IQueryable is that fact that literally any type of expression chain might be applied. This can be problematic when the query is abused, such as returning large record sets or performing complex joins with a negative impact on performance. What if you could enforce a simple rule, such as “This query may never return more than ten items”?

Here’s a query with no limits - the same one that returned 53 results in the previous example.

var results = query.Where(t => t.IsTrue &&

t.Id.Contains("aa") &&

t.Expires < DateTime.Now.AddDays(100))

.OrderBy(t => t.Id);

Here’s the registration:

static Expression ExpressionTransformer(Expression e)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Before: {e}");

var newExpression = new GuardRailsExpressionVisitor().Visit(e);

Console.WriteLine($"After: {newExpression}");

return newExpression;

}

// wrap and intercept

var query = new QueryHost<Thing>(ThingDbQuery);

query.CustomProvider.RegisterInterceptor(ExpressionTransformer);

Notice that the expression is passed to the GuardRailsExpressionVisitor. If you recall from previous posts, the ExpressionVisitor class provides an easy way to traverse and modify expression trees. The tree is recursively iterated by the base class, then methods are called that can be overridden to inspect the node on the tree. The overridden methods either return the original expression or a modified one, resulting in the transformation of the tree. To implement the guard rails, there are three possibilities:

- The “take” exists but is less than ten (no change)

- The “take” exists but is greater than ten (“take” is modified to 10)

- The “take” doesn’t exist (“take of ten” is added)

This implementation is simple and assumes a constant is being used. Keep in mind a reliable implementation must handle edge cases, such as nested “take” statements in inner queries. Other edge cases include statements that use lambda expressions to reference properties and using the result of a method call instead of a constant.

When you specify “take” on a query, what really happens is an extension method of IQueryable is called that exists on the Queryable class. A query like this:

var results = query.Take(10);

Uses an extension method that looks like this:

public static IQueryable<TSource> Take<TSource>(this IQueryable<TSource> source, int count)

{

if (source == null)

{

throw Error.ArgumentNull(nameof(source));

}

return source.Provider.CreateQuery<TSource>(

Expression.Call(

null,

IQueryable<object>(Queryable.Take).GetMethodInfo()

.GetGenericMethodDefinition().MakeGenericMethod(TSource),

source.Expression,

Expression.Constant(count)));

}

Here’s the code to intercept the method call and enforce the “take” rule:

protected override Expression VisitMethodCall(MethodCallExpression node)

{

if (node.Method.Name == nameof(Queryable.Take))

{

TakeFound = true;

if (node.Arguments[1] is ConstantExpression constant)

{

if (constant.Value is int valueInt)

{

if (valueInt > 10)

{

var expression = node.Update(

node.Object,

new[] { node.Arguments[0] }

.Append(Expression.Constant(10)));

return expression;

}

}

}

}

return base.VisitMethodCall(node);

}

The expression is only overridden when the value is out of range. Instead of rebuilding the original expression from scratch, the Update method (available on most expressions) makes it easy for you to create a copy of the expression and override the parameters you want to. The first argument points back to the parent query, so the second one is what we override to the new value. Running this results in the following:

Notice that the higher take of 50 is modified while the lower take of five stays the same. This works well for replacing an existing take, but what if no take is specified at all?

The solution is here:

public override Expression Visit(Expression node)

{

if (first)

{

first = false;

var expr = base.Visit(node);

if (TakeFound)

{

return expr;

}

var existing = expr as MethodCallExpression;

var newExpression = Expression.Call(

typeof(Queryable),

nameof(Queryable.Take),

existing.Method.ReturnType.GetGenericArguments(),

existing,

Expression.Constant(10));

return newExpression;

}

return base.Visit(node);

}

Remember that Visit is called recursively, so the first flag ensures the top-level logic is only run once. The expression tree is parsed and if the take expression was encountered, it simply returns the modified expression. Otherwise, it creates the take expression. The top-level expression is always a call that returns the result. To implement take, we simply create our own method that applies the take to the wrapped method and returns the results. The story is told through the Expression.Call parameters.

-

typeof(Queryable)is the static class that definesTake -

nameof(Queryable.Take)is the name of the method to call (Take<T>()) -

existing.Method.ReturnType.GetGenericArguments()closes the generic type becauseTakerequires a type parameter. The query is anIQueryable<T>so the existing method must implementTas the generic argument (in this case,TisThing). -

existingis the first parameter, or what the extension method applies theTaketo. This is the original expression, so the result of that expression is what theTakewill be applied to. -

Expression.Constant(10)is the number of items toTake.

You can see the Take added here and confirm the result set is limited.

The expression has been intercepted and transformed! For the next (and last) example I tackled a real-world problem.

Intercept Binary Evaluations

A customer of ours asked if there is a way to understand why certain items are selected and others are filtered out when a query is executed. In other words, for each item, what is the part of the query that failed? The solution is tricky. For example, if the query is sent to the database then there is really no decision to intercept: the EF Core provider will create the SQL syntax and pass it along to the database. For in-memory selection it is possible to capture the decision. First, I created a BinaryInterceptorVisitor<T> to transform the expression tree for a given type.

When you build a query with filters, the “where” clause becomes a set of binary expressions. For example, the following query:

var list = query.Where(

t => t.IsTrue &&

t.Id.Contains("aa") &&

t.Expires < DateTime.Now.AddDays(100))

.OrderBy(t => t.Id).ToList();

Ends up looking like this for the filter:

AndAlso(t.IsTrue,

AndAlso(

t.Id.Contains("aa"),

IsLessThan(

t.Expires,

DateTime.Now.AddDays(500))))

First, let’s capture the value of t.

Capture the Entity

I added a field named instance to capture the entity being evaluated. To keep it simple, I just declare it as an object:

private static object instance;

I created a method to set the instance:

private static void SetInstance(object instance)

{

BinaryInterceptorVisitor<T>.instance = instance;

}

To make it easier to build an expression that calls the method, I added some helper methods that resolve the data structure for method information called MethodInfo. These are the flags needed to find a static method:

private static readonly BindingFlags GetStatic =

BindingFlags.Public | BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Static;

This is the method to get the MethodInfo data:

private static MethodInfo GetMethod(string methodName) =>

typeof(BinaryInterceptorVisitor<T>)

.GetMethod(methodName, GetStatic);

Here is the reference to the method:

private static readonly MethodInfo SetInstanceMethod = GetMethod(nameof(SetInstance));

Lambda Expressions

The “where” clause of the query is built as a LambdaExpression with this signature:

Func<T, bool> Where;

Each entity is passed into the filters and ultimately the filter either passes or not. Here is the overload to intercept a lambda expression:

protected override Expression VisitLambda<TValue>(Expression<TValue> node)

The expression to intercept has a specific signature. It will have exactly one parameter of type T and a return value of type bool:

if (node.Parameters.Count == 1 &&

node.Parameters[0].Type == typeof(T) &&

node.ReturnType == typeof(bool))

When the right lambda expression is intercepted, our code sneaks in to nab the entity:

var returnTarget = Expression.Label(typeof(bool));

var lambda = node.Update(

Visit(node.Body),

node.Parameters.Select(p => Visit(p)).Cast<ParameterExpression>());

var innerInvoke = Expression.Return(

returnTarget, Expression.Invoke(lambda, lambda.Parameters));

var expr = Expression.Block(

Expression.Call(SetInstanceMethod, node.Parameters),

innerInvoke,

Expression.Label(returnTarget, Expression.Constant(false)));

return Expression.Lambda<Func<T, bool>>(

expr,

node.Parameters);

The key to intercepting the type is to use a BlockExpression. This expression allows you to combine multiple expressions that run sequentially. Only the result of the final expression is used for the result (although you can capture the result of other expressions using variables). The steps in the code look like this:

- Create a “return target.” Think of this as a variable to capture the return value of the original lambda expression. In expression parlance, this is a “label.”

- Transform the lambda by using

Updateand visiting its parts (the body of the expression and the parameters). This is important because the body contains the binary expressions that also will be transformed, so the lambda expression itself must be replaced. - Create an invocation that calls the original lambda expression and captures its return value.

- Create an expression block:

- The first expression grabs the parameters from the lambda and uses them to call the

SetInstancemethod. The parameter is the entity being evaluated, so this effectively captures the entity for inspection. - The second expression is the invocation of the original lambda expression.

- The final parameter is the “binding” to the return value with a default value of

false. This is always overwritten with the actual result of the original expression.

- The first expression grabs the parameters from the lambda and uses them to call the

- Finally, a lambda expression is returned with the same signature as the original.

The code takes this:

Func<T, bool> lambda = t => Where(t);

And transforms it into this:

Func<T, bool> lambda = t =>

{

BinaryInterceptorVisitor<T>.SetInstance(t);

return Where(t);

};

Now that the value is captured, the next step is to understand which binary expressions succeed or fail.

Wrap a Binary Expression

The key to understanding how to capture the result is logical. Very logical. As in, logic gates. Right now, we have a Func<T,bool> that could be true or false. The trick is to inject our own code that captures the rule before it is evaluated, then captures the result whether it is true or false. This must be done using only binary expressions. Here’s some pseudo code:

- Grab the rule

- If the rule succeeds, capture the success

- Else if the rule fails, capture the failure

Logic provides a means to wrap the expression in a way that preserves the original value. Let’s review our basic logic statements:

Logical OR left OR right = OrElse(left, right)

- If left

- Then true

- Else

- If right

- Then true

- Else false

Notice that the right is only run if the left is false. Essentially, think of it as “when the left is false, pass through to the right.” This is how we intercept the expression before it’s called:

OrElse([our code => return false], [existing code]);

…and another logic statement:

Logical AND left AND right = AndAlso(left, right)

- If left

- Then

- If right

- Then true

- Else false

- Else false

Basically, you can think of it as a flipped OR because “when the left is true, pass through to the right.”

This makes it easy to capture success:

AndAlso([existing code], [our code => return true]);

But how do we capture failure? What we need is to call our code for failure when the previous logic returns false:

OrElse(AndAlso..., [our code => return false]);

Therefore, the full interception requires four parts:

-

binary- the original rule to intercept -

orLeft- the snapshot of the rule before it is run -

andRight- capture the success case -

orRight- capture the failure case

This is the actual code to replace the existing expression:

return Expression.OrElse(

orLeft,

Expression.OrElse(

Expression.AndAlso(binary, andRight),

orRight));

So, what do the implementations of orLeft and our other interceptors look like? There are two fields defined that capture the level of nesting:

private static int evalLevel = 0;

private int binaryLevel = 0;

The binaryLevel keeps track of the levels as the expressions are parsed. This is used during the definition phase as the structure is being updated. The evalLevel keeps track of the nested level during the runtime or implementation phase.

The BeforeEval method checks to see if it is at the top level. If so, it writes the value of the current entity that was captured by the lambda expression override and resets the evaluation level. Otherwise, it increments the level. Then, it writes the rule. The text is indented based on the current level for readability.

public static void BeforeEval(int binaryLevel, string node)

{

if (binaryLevel == 1)

{

Console.WriteLine($"with {instance} => {{");

evalLevel = 0;

}

else

{

evalLevel++;

}

Console.WriteLine($"{Indent}[Eval {node}: ");

}

The AfterEval method writes out the result (success or failure) and decrements the level. It also writes a closing brace if the evaluation is after the top expression.

public static void AfterEval(int binaryLevel, bool success)

{

var result = success ? "SUCCESS" : "FAILED";

Console.WriteLine($"{Indent}{result}]");

evalLevel--;

if (binaryLevel == 1)

{

Console.WriteLine("}");

}

}

In the BinaryExpression override method, the method calls are built with the appropriate parameters:

binaryLevel++;

var before = Expression.Call(

BeforeEvalMethod,

Expression.Constant(binaryLevel),

Expression.Constant($"{node}"));

var afterSuccess = Expression.Call(

AfterEvalMethod,

Expression.Constant(binaryLevel),

Expression.Constant(true));

var afterFailure = Expression.Call(

AfterEvalMethod,

Expression.Constant(binaryLevel),

Expression.Constant(false));

Next, the binary expression inputs are created. These use expression blocks that call the desired method then return the proper bool.

var orLeft = Expression.Block(

before,

Expression.Constant(false));

var andRight = Expression.Block(

afterSuccess,

Expression.Constant(true));

var orRight = Expression.Block(

afterFailure,

Expression.Constant(false));

The existing binary expression is replaced with a call to visit the left and right nodes. This ensures downstream expressions are also intercepted.

var binary = node.Update(

Visit(node.Left),

node.Conversion,

Visit(node.Right));

binaryLevel--;

Finally, the entire expression is replaced with the logic shown earlier.

Logically, the binary expression is replaced with this tree:

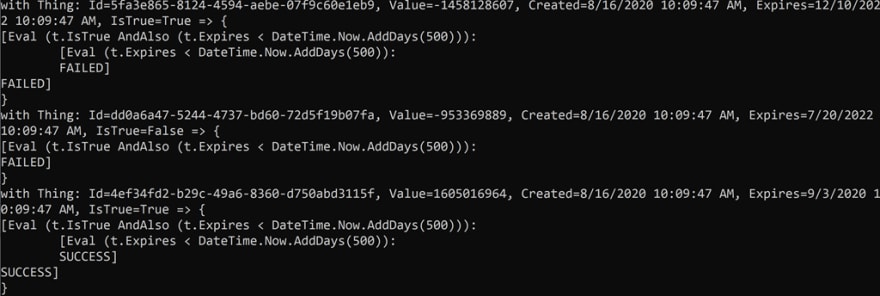

Here is the result of a run:

In the first example, IsTrue is true so the evaluation continued to the inner rule. The expiration date is December 10th, 2022, which is more than 500 days in the future, so it failed. This results in the entire expression failing.

In the second example, IsTrue is false so the expression failed immediately.

Finally, IsTrue is true and the expiration date of September 3rd, 2020 is less than 500 days in the future, so the entire expression succeeded.

💡 Tip : the approach can be enhanced by handling more than binary expressions. For example, the expression

AndAlsorequires aboolfor each side, so you could override the member access (the expression that gets the value ofIsTrue) and show that result like a nested rule. You could also intercept the evaluation of expressions likeGreaterThanto show the actual values being compared.

Conclusion

The code covered in this blog post is available here:

JeremyLikness

/

QueryEvaluationInterceptor

JeremyLikness

/

QueryEvaluationInterceptor

An example of intercepting IQueryable executions to parse and transform the query.

QueryEvaluationInterceptor

An example of intercepting IQueryable executions to parse and transform the query.

I hope these explorations of expressions help shed light on a powerful tool in the .NET toolbox. To make expressions more approachable, I’ve been working on an Expression Power Tools library to simplify working with expressions. For example, this code:

var query = new QueryHost<Thing>(ThingDbQuery);

query.CustomProvider.RegisterInterceptor(ExpressionTransformer);

Is simplified to this:

var query = ThingDbQuery.CreateInterceptedQueryable(ExpressionTranformer);

If you’re interested in expressions, take a look!

Regards,

Top comments (1)

This is a very well written post. Thank you.