https://ctftime.org/task/16546

I heard it's raining flags somewhere, but forgot where... Thankfully there's this weather database I can use.

Running the binary prints out a prompt asking for a city to fetch weather data for. Sadly, the flag is not "none" so I guess we should just give up and call it a day.

$ ./weather

Welcome to our global weather database!

What city are you interested in?

London

Weather for today:

Precipitation: 1337mm of rain

Wind: 5km/h W

Temperature: 10°C

Flag: none

Overview

First things first, open IDA.

We have 46 functions, half of them "unreachable" from main and all look very similar referencing the same memory and have a similar execution tree shape.

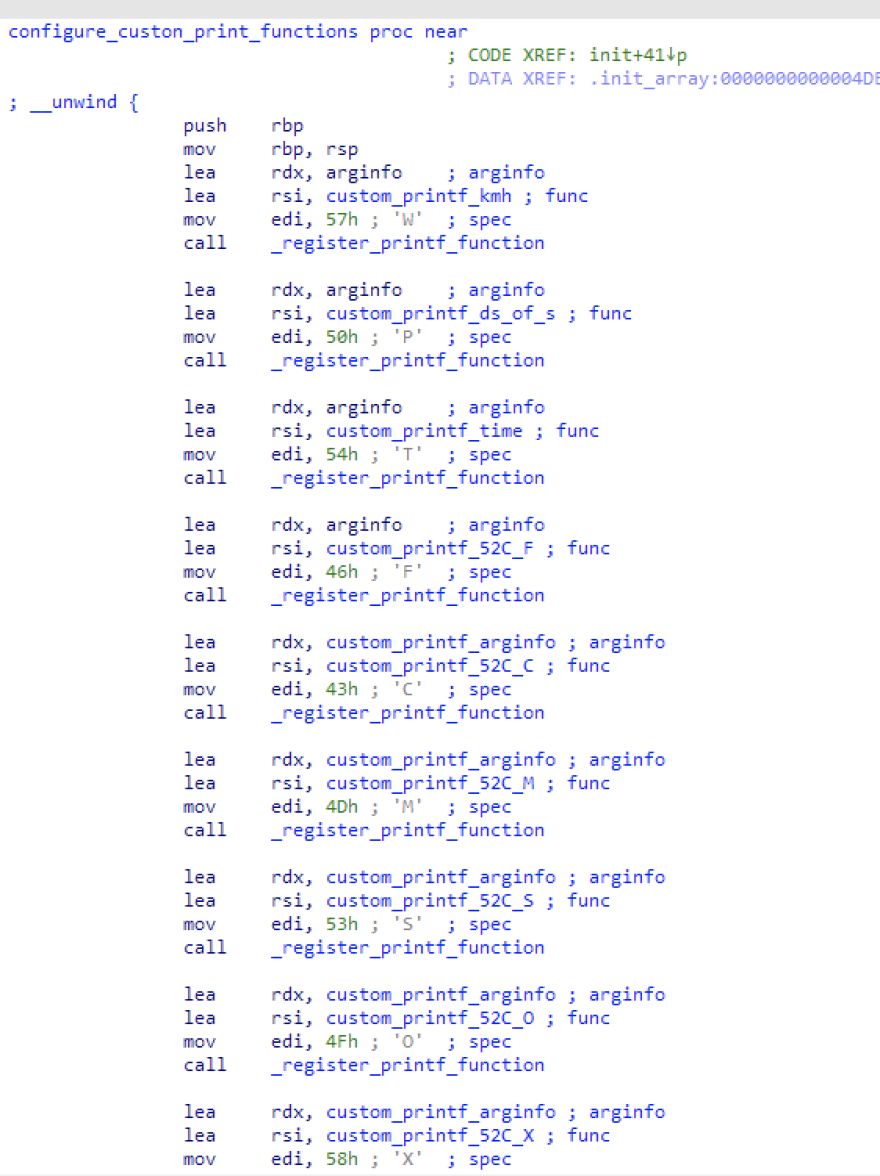

Additionally, one function (we called it configure_custon_print_functions) references all of those "unreachable" functions, passing them as a reference to register_prinf_function.

configure_custon_print_functions is called on init (before main) and by putting a breakpoint at the functions it registers we can see some of them are executed in a normal execution flow.

configure_custon_print_functions

register_prinf_function

From the GNU manual

12.13.1 Registering New Conversions

The function to register a new output conversion isregister_printf_function, declared in printf.h.

Function: int register_printf_function (int spec, printf_function handler-function, printf_arginfo_function arginfo-function)

For example, to register a handler for %Y we would call register_printf_function

int y_custom_handler(FILE *stream, const struct printf_info *info, const void *const *args) {

// here we would implement our custom formatting

}

void main(){

printf_arginfo_function args;

register_printf_function('Y', y_custom_handler, &args);

}

The struct print_info stores metadata about the format string, for example %52Y would set print_info->width = 52 and %52.3Y will set both width and print_info->perc = 3.

Disassembling main we can see that the last printf which is responsible for printing Flag: none is printed using a special printf function which is assigned the letter %F . To my surprise , the F handler itself calls fprintf another time, this time with a new format string %52C%s.

As most "unreachable" functions were used while registering the custom printf functions we can assume they will be called eventually by printf, for that reason we started reversing these functions. Just to make sure they are all called, we made a Frida script to trace the execution of these functions and indeed most of them were called.

a VM?

Reversing the functions we discovered most of them were almost identical, doing the same checks at the beginning, after which each handler did a different operation at the end. On top of that, the only handler that called fprintf recursively was C

Tip: Looking in HexRays decompiled c, rather than assembly helped us understanding which handler is what operation much faster.

We found that the following handlers were registered:

-

Massignment -

Saddition -

Osubtraction -

Xmultiply -

Vdivide -

Nmodulu -

Lshift left -

Rshift right -

Exor -

Iand -

Uor -

Cconditional recursive jump

Each of the above commands takes the printf_info metadata and deduces from it the source and destination memory regions. There are two possible memory regions: one is just a linear memory we called "stack" and the second points to the start of the format string.

'%52C%s',0

'%3.1hM%3.0lE%+1.3lM%1.4llS%3.1lM%3.2lO%-7.3C',0

'%0.4096hhM%0.255llI%1.0lM%1.8llL%0.1lU%1.0lM%1.16llL%0.1lU%1.200llM%2.1788llM%7C%-0.0C',0

.data:0000000000005080 ; char a52cS[]

.data:0000000000005080 a52cS db '%52C%s',0

.data:0000000000005087 a31hm30le13lm14 db '%3.1hM%3.0lE%+1.3lM%1.4llS%3.1lM%3.2lO%-7.3C',0

.data:00000000000050B4 a04096hhm0255ll db '%0.4096hhM%0.255llI%1.0lM%1.8llL%0.1lU%1.0lM%1.16llL%0.1lU%1.200l'

.data:00000000000050B4 db 'lM%2.1788llM%7C%-6144.1701736302llM%0.200hhM%0.255llI%0.37llO%020'

.data:00000000000050B4 db '0.0C',0

C - Compare Instruction

the compare instruction is implemented in the printf custom %C handler. This instruction has four modes:

1) lower-than jump

2) greater-than jump

3) equal-zero jump

4) always jump.

If the jump is taken, fprintf is called again (which makes it recursive) with a new format string. This format string is calculated by taking printf_info->width as an offset from the original format string.

So the format string %52C%s is actually the instruction

jump 52

# do 52 stuff...

printf(%s) # the regular %s

Knowing how the different instructions are implemented we can now write a python script to convert the format string to a "toy" assembly language that will be easier to read. We ended up writing a VM able to compile format strings to code, dump the assembly and emulate the memory mapping.

Stage 1

Disassembling the format string we can see the following assembly. We start at 0, jump to 52 where the first character of our input is loaded onto the "stack". We then jump to address 7 where we loop until a counter is zero or more.

The code at address 7 is a function that takes three arguments: character, offset to decode from and length. This function will use the first argument (our inputs first character) as a key to decrypt the data at offset 200. By "chance", this is the same memory that is checked against in the last compare of block 52 and also the address where we jump in case the compare is positive.

========== 0 ==========

C.always 52

printf(%s)

# memsmoc

========== 7 ==========

(M) stack[(int) 3] = a52[stack[(int) 1]]

(E) stack[(int) 3] ^= stack[(int) 0]

(M) a52[stack[(int) 1]] = stack[(int) 3] # decrypt fromat_string[200 + index]

(S) stack[(int) 1] += 4 # increase

(M) stack[(int) 3] = stack[(int) 1]

(O) stack[(int) 3] -= stack[(int) 2] # counter -=

(C) C.lt 7 stack[(int) 3] < 0 # while counter < 0

========== 52 ==========

stack[(int) 0] = a52[4096] # user input

stack[(int) 0] &= 255 # first letter of user input

stack[(int) 1] = stack[(int) 0] # copy the first letter

stack[(int) 1] <<= 8

stack[(int) 0] |= stack[(int) 1]

stack[(int) 1] = stack[(int) 0]

stack[(int) 1] <<= 16

stack[(int) 0] |= stack[(int) 1] # c

stack[(int) 1] = 200 # func_7(c, 200, 1788)

stack[(int) 2] = 1788

C.always 7

at52[6144] = 1701736302 # "none"

stack[(int) 0] = a52[200] # get first char from format_string[200]

stack[(int) 0] &= 255

stack[(int) 0] -= 37 # fromat_string[200] == '%'

C.eq 200 stack[(int) 0] == 0 # check if decrypted stage two successfully

As this function takes into account only the first character we can try all ascii characters until one of them proves to be the correct answer (one where the jump of the last compare is taken). After trying some inputs we found that 'T' was a valid input 🎊

Stage 2

Executing the VM with the input of 'T' the conditional jump is taken and the new code at 200 is executed flawlessly. We can now dump it out to human readable assembly

the main code for stage 2

========== 200 ==========

stack[(int) 4] = 5000

stack[(int) 0] = 13200

C.always 337 # this loops 400~ times

stack[(int) 0] = 0

C.always 500 # loop over input and mangle it

C.always 1262 # validate mangled input using xor

C.eq 653 stack[(int) 0] == 0 # check if output of 1262 is zero

# if so, 653 decrypts winning print command (using original input as key)

Writing the same code in c would result in

int func_200() {

func_337(5000, 13200);

mangle_input(); // func_500;

if (validate_input() == 0) { // func_1262

// print_flag is a calculation over input so one

// cannot just execute print_flag without the correct input

print_flag(); // func_653

}

}

Mangling Input

Nothing smart here, just go line by line and reverse the assembly to python.

It took me time to realize the key to this function is it's recursive manner. Basically, it decreases some input number by different rules, counting how much iterations it takes until this number turns to zero, returning the number of iterations in stack[0].

Our result "decompiled code" looks something like this

# 500:

def mangle_loop(input_s):

output = [0 for x in range(len(input_s))]

for i in range(len(input_s)):

c = input_s[i]

c = ord(c) ^ (stage_two_main[i * 2] & 0xff)

c += do_470(i + 1) + 1

c = c & 0xff

output[i] = c

return output

def do_470(var_0):

var_1 = var_0 - 1

var_1 -= 1

if var_1 == 0: # 397

return 0

if var_1 < 0:

return var_0 - 2

# var_1 > 0 :428

var_1 = var_0 % 2

if var_1 == 0: # :405

var_0 = var_0 // 2

if var_1 > 0:

var_0 *= 3

var_0 += 1

var_0 = do_470(var_0)

return var_0 + 1

Reversing the Input Validation

- We know how to transform our input in the exact same way function 500 does.

- We know that the result of function 1262 is stored in

stack[0] - The last condition of at the end of function 200 is the last check executed and it looks like we are failing it. Any input we had manually tried did not match the condition.

All of the above convinced us that if 1262 would return 0, our jump to 653 would print out the flag.

Summing up, 1262 is a validation function that:

- takes as an input the mangled bytes from our input string

- returns the result on

stack[0]where 0 means the validation was successful

The begginning of code at 1262

========== 1262 ==========

stack[(int) 0] = 0 # result = 0

stack[(int) 1] = 0

stack[(int) 1] += 4500 # mangled user input offset

stack[(int) 1] = a52[stack[(int) 1]] # var1 = mangled[0]

stack[(int) 2] = 0

stack[(int) 2] += 1374542625

stack[(int) 2] += 1686915720

stack[(int) 2] += 1129686860 # var2 = (int) (1374542625 + 1686915720 + 1129686860)

stack[(int) 1] ^= stack[(int) 2]

stack[(int) 0] |= stack[(int) 1] # result |= var1 ^ var2

This code snippet is repeated for every 4 characters from 0 to 24, each time with a different value in var2. We know the first letter is 'T' so breaking the first 4 letters should be possible using simple brute force on the remaining 3 letters. We did just that and got the first 4 letters: "TheN" 🥳 .

Continuing from here we should have used z3 to create constraints and solve this efficiently but we were lazy, so instead we just continued brute forcing 4 letters a time. This took around 3 hours using 1 cpu core in python.

The brute forcing code is simple: try any combination of 4 ascii letters, send them to mangle_function and then xor the result with the appropriate value (from 1262). A valid result is one where mangle(input[i:i+4])) ^ magic == 0

pseudo brute force code

import itertools

def brute():

start = '0'

end = 'z'

magic = ctypes.c_int(1374542625 + 1686915720 + 1129686860).value

for i in itertools.product(range(ord(start), ord(end) + 1), repeat=4):

s = ''.join([chr(x) for x in i])

out_mem = mangle_input(s)

result = arr_to_int(out_mem)

if result ^ magic == 0:

print('found input!', s)

Flag:

CTF{curs3d_r3curs1ve_pr1ntf}

The full vm, brute-force and annotated assembly can be found at:

https://github.com/bitterbit/ctf/blob/master/google-ctf-qual-2021/weather

Top comments (0)