As a quick note, I released this post on my blog yesterday, so it can get to be (as I tend to be) a bit rambling. Oh, and the original text is on GitHub (licensed CC-BY-SA), so if anything seems muddy, by all means:

- Leave a comment here,

- Leave a comment on the blog,

- File an issue on GitHub, or

- Add a pull request!

I have recently been investigating some possible projects that would benefit from having a simple browser extension to pass along real-time data on the user’s actions. It’s simple enough, but has enough detail to make a viable post.

In this case, our extension is going to report every visited URL to a configurable remote address.

The Short Version

A browser extension for both Firefox and Chrome-based web browsers is some JavaScript code with a Manifest file. If you’re not packaging them up for the official download sites and are familiar with JavaScript, you can look up the manifest and work from there.

It’s a little bit more complicated than that, but not a lot.

Project Layout

A simple browser extension project has four parts.

-

manifest.json, which is (unsurprisingly) the project’s manifest file, - Some JavaScript code that does what the extension needs,

- A folder for any assets that might be used, and

- Icons to represent the project.

In the case of URL Rat, it looks something like this.

├── icons

│ ├── border-48.png

│ └── border-96.png

├── LICENSE

├── manifest.json

├── README.md

└── url-rat.js

LICENSE and README.md were created when I started the repository, and I created the images with ImageMagick, based on the suggestions on Mozilla’s tutorial.

convert -size 48x48 xc:#6187db border-48.png

convert -size 96x96 xc:#6187db border-96.png

Or whatever color I actually used. It’s not in my command history, for some reason. You can create a real icon, if that interests you for the purpose of the project.

Manifest Destiny

Because my plug-in needs to actually do something, I made some changes to the sample suggested by the Mozilla tutorial linked above.

{

"manifest_version": 2,

"name": "URL Rat",

"version": "1.0",

"description": "Sends each visited URL to a local server.",

"permissions": [

"<all_urls>"

],

"icons": {

"48": "icons/border-48.png",

"96": "icons/border-96.png"

},

"browser_specific_settings": {

"gecko": {

"id": "urlrat@example.com"

}

},

"content_scripts": [

{

"matches": ["*://*/*"],

"js": ["url-rat.js"]

}

]

}

Obviously, I changed the name, description, and script name. If this ever becomes a real project, the ID will need to change. But the two important items to talk about are the following.

-

matchesprovides a list of patterns that a visited URL needs to match. In the case of the Mozilla example, it’s only for Mozilla pages, whereas mine will be active on all pages, hence*://*/*, all protocols (HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, FTPS, and whatever else modern browsers support), all hosts, and all files on that host. -

permissionsis the list of resources the extension needs to access. I hate that this needs to be<all urls>, allowing it to send data to and receive data from any page on the Internet, since that’s a potential security problem that a bad actor or clumsy developer could exploit. However, since we’ll eventually want to configure the destination URL to point to any server (not in this post), it does make sense to request that flexibility, regardless.

I tried to narrow permission to a specific URL, like the one actually used in the HTTP requests, but couldn’t get that to work unless I specifically visited my own server, which is…somewhat less than useful.

Code

The code to capture and send every visited URL is simple enough, if a bit obnoxious to deal with the asynchronous code.

The first line is just configuration. You’ll need your own server listening on a port, somewhere, and url should point there.

var url = 'http://localhost:8080/';

This gets us our current URL.

var currentUrl = document.location.href;

The aforementioned obnoxiousness. We create an asynchronous, anonymous function to call fetch, so that we can call it immediately and not get yelled at by the interpreter for using await inside something other than an asynchronous function.

(async () => {

Now, we make the request. Note that it’s an HTTP POST request, so that it can usefully carry a message body (with the URL as that body), but the server I threw together wasn’t recognizing the bodies, so I also stuffed it into the header as X-This-Is-The-Url. The HTTP specification has no problem with you adding headers, as long as they all start with X- to avoid confusing any parsing code.

const rawResponse = await fetch(url, {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Accept': 'text/plain',

'Content-Type': 'text/html',

'X-This-Is-The-Url': currentUrl

},

body: currentUrl

});

Now, we just need to wait for the response to come back and (if desired) do something with it.

const content = await rawResponse;

console.log(content);

})();

Once debugging is complete, we can scrap the logging statement entirely, since it only clutters the console window.

Testing the Extension

For Firefox, the Mozilla tutorial is right on. But to summarize...

- Navigate to

about:debugging, - Click This Firefox on the left-hand panel,

- Click Load Temporary Add-on ,

- Navigate to your extension’s folder,

- Select any file in that folder, such as

manifest.json, and - Click Open.

Assuming there were no errors, it should run until you reload or unload it, or until you shut Firefox down.

On Chrome (or Chromium, and probably most browsers built on Chromium, but I’m not testing them…), it’s similar.

- Navigate to

chrome://extensions/, - Switch to Developer Mode to the upper-right,

- Click Load Unpacked to the upper-left,

- Navigate to your extension’s folder,

- Click Open.

Chromium will complain about the gecko.id field in the manifest, but that won’t affect your testing.

Where Next?

This is already getting too long for a “tip,” so I’ll save it for next week, but the obvious next big step to make this usable would be to add a configuration pop-up to replace the current destination URL with something other than http://localhost:8080. If you want to get to it before I do, the Mozilla tutorial links to “a more complex extension” that includes a toolbar button and a pop-up window. The Favourite Coluor is closer to the idea of a configuration page, too.

This would basically be that, but with a single place to fill in a URL (maybe validate it) and, optionally, a switch to turn the feature on and off to allow people to step out of the Panopticon when necessary.

Check back in next week, for that.

Packaging

Browser extensions are ZIP files of the folder contents (not the folder itself), renamed to *.xpi for Firefox. Here’s Mozilla’s example. It can then be sent to whoever needs to sign it, and you have yourself a browser extension.

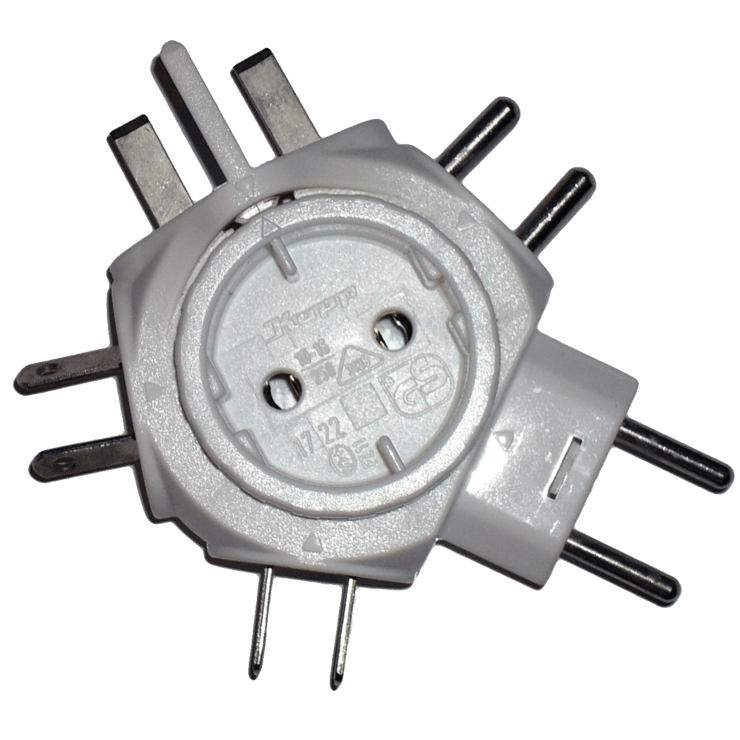

Credits : The header image is Fotowerkstatt by Mattes, released into the public domain.

Top comments (0)