Looking back at test automation in a product development team for describing patterns of success for research purposes, we identified themes where the experienced success significantly differed from what the literature at large was describing. With those lessons, I moved to a new organization and took upon myself to facilitate a transformation to whole-team test automation over multiple teams, one at a time, one after the other. In this writeup of a talk, we will revisit the research from one organization two years ago with lessons from another in the last two years.

I will introduce you to my core patterns to practice-based test automation transformation. I can't promise a recipe I would apply, as my recipe changes and adapts as I work through teams, but I can promise experiences of the same patterns working on multiple occasions as well as examples of how my go-to patterns turned out inapplicable. We'll discuss moving from specialist language to generalist language, visualizing testing debt and coverage, using visualization to showcase progress made of continuous flow of small changes, choosing to release based on automation no matter how little test automation there is, and growing individual competencies by sharing YOUR screen when working together.

This writeup is of a talk I prepared for Selenium Conference India/Virtual 2022, and I write it for same reasons I do talks: learning by structuring my thoughts and to snapshot my current imperfect understanding.

In terms of whole-team test automation, I'm inclined to start with discussing the technology choices. Here's the choices I see around me.

A core to choices at Vaisala is the idea that we build embedded devices, as well as hosted and cloud-based systems and services.

Building embedded devices has a special requirement for automating, that is to automate also on physical interfaces. We have around a proprietary system we call 'plexus', and you can't really find anything on it by googling. It's a combination of building hardware that can be driven by software to control other hardware. What matters is what we can do with it - we can automate not giving a device power, turning it on and off, and pressing physical buttons with various purposes. And for that purpose we've create something that is written in python and is for now a Robot Framework library. For webUIs (a lot of devices host a web server for administrative user interface) it's been Selenium within Robot Framework. Basically, plexus is Robot Framework + internal libraries + virtualisation.

As we've moved along in the last two years, I've been driving an effort to not solely rely on Robot Framework, but in steps move towards a general purpose language, namely Python. While we're sometimes struggling with some folks strictly believing pytest is a unit test framework which it isn't, we've made significant steps both in embedded software and other software on running some of the new tests in pytest + selenium, enough to learn we could remove Robot Framework should we want to. There are forces - people having specialty skills in the Robot Framework language - keeping it in place and we're learning on our choices incrementally.

In addition to Selenium, we've started using Playwright in various places. We've been running the two side by side enough to come to terms with the idea that specialty skills and interest may drive the choice, and allowing for people to follow their energy helps us move to a good place in test automation doing relevant work for us. Both exist and it is not a problem. Someone already fluent in Selenium will work better with Selenium. Someone new seems to enjoy looking at the new, and working better with Playwright. No real difference in what they can test or how fast, even with the run time duration differences - it's machine time and we're not fine-grained enough to optimize minutes in most of our teams.

Teams that don't have an embedded C + Python link or Python as their main language tend to favor not introducing Python to their mix. They run with languages their teams already use, typically testing in Javascript and Typescript, and with a mix of Cypress and Playwright. JS/TS Playwright is not just the APIs but also the runner, and confusion around 'what is what' is a bit of challenge.

For whole team test automation, we've come to appreciate that tools matter for the language of choice. Choosing Robot Framework language, we are recruiting Robot Framework programmers. Choosing a general purpose language, we have been more successful in sharing the work with whole teams and keeping the automation around and operational when the core specialists decides to pursue career steps elsewhere. Choosing general purpose language, recruiting testers is a notch harder, as most people skilled in Robot Framework have a barebones knowledge of the language doing very limited set of programmatic tasks for purposes of testing.

That's the world I live in now.

Before I joined Vaisala, I was working with F-Secure. Just before I pursued career steps elsewhere, we published an article about how we did automation in a team responsible for corporate windows endpoint security product. The team and how we automated was fascinating to me, because it was the first experience of all the experiences I have had with automation where I believed, honestly believed, that automation was worthwhile and working as it should for purposes of testing. We did particularly well with our Test Automation there - why? We decided to look at it with help of university research group specializing in test automation process improvement and assessment, and the article is the outcome of that collaboration.

We had automation around, even in that organization before. We had grown to understand what good looks like by working on it - and failing with some of our smaller scale successes - over more than a decade. The whole team ownership seemed like a central aspect to success. To live through changes in organization and people, it needs to be for everyone. EVERYONE. It cannot leave with any single one of us became a criteria for success.

At start of writing the article, we thought it was the architecture and the services we had created. We attributed a lot of success to testability meaning that there was higher chance of changing product to be easier to test to implementing hard test automation, and automation was possible. Same people in same teams could choose to automate or change the product. I find we misattributed success to technology, that was shared ownership - whole team ownership.

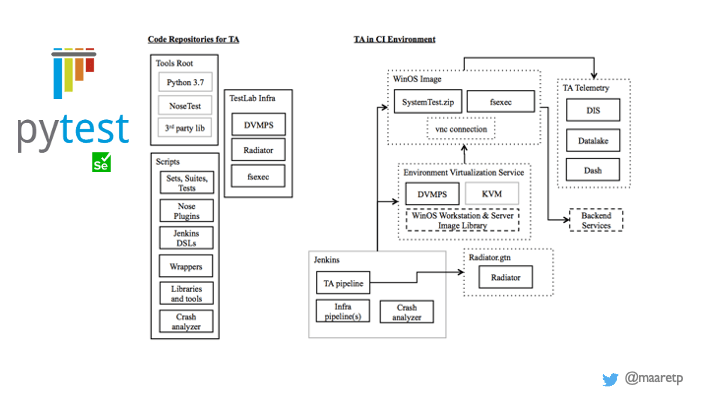

We were happy and proud with the automation architecture we had in use. Particularly the parts about telemetry (coverage of automation in test vs. coverage of users in production, and analyzing results in scale while tests were running). It was running on Python Nosetest, later Python pytest and a lot of self-created services. While we had a tiny bit of Selenium in the overall system, a contributing factor many considered to be important was that a lot of the automation was done without a GUI involved. Also, most GUIs weren't web but windows, so Selenium would not have been a choice for driving them anyway.

We had some great things we loved on services we shared for automating. Particularly the idea of getting 14 000 fresh windows operating systems running on virtual machine a day, and wait time of under 5 seconds to have new machine running and ready to test. Replacing the internal system for virtualization with cloud-based one could only make the experience slower.

So it was not the technology choice, even if the conversation we have in conferences and communities so often is around it. What was it then? I hinted on it already, with the how I titled this talk: the whole team ownership. We did particularly well with automation, and the whole definition of success was on automation doing the work without causing the pain to exist, and showing up positively on various outcomes.

With the same kind of success criteria in mind, I would look at teams I have now worked with at Vaisala during the last two years. I think all teams are doing well with generally available criteria of success in automation, having some and having more over time. There is a general principle of hiring people who will automate, and automation exists around in scale. Yet still I would split teams into three categories:

Ones I consider successful.

Ones I consider not successful.

Ones I haven't yet been around enough to know if I would consider them successful, but I am around trying to contribute to that success.

All the ones I mark with a FAIL are successful if you ask the single tester who has been building automation in that team. I consider it a fail since I have already seen some of these have the single tester leave, and the automation vanish. Investing 10 years into building something you're proud of to only have it eradicated the moment you leave organization wouldn't pass my criteria of success.

Success today is a snapshot of how we use our time on sharing today. It is easy to break by a management specialization decision. It is easy to break by asking to cut corners. For success to exist, it needs to become part of values to have whole team ownership and capability.

Let's still discuss this particularly well in more detail. What does it look like? Personally, I like looking at it with a visualisation on level of code.

In a minute-long video, we can see a team progress on their test automation repository over a year of time, day by day for the year I spent with them. What we look at in the demo is that there are a lot of characters moving around making changes, it is not a single person, it is the whole team. They create new tests and services, maintain the old. It's not just the testers in the team who contribute, while it is clear that there is enough work for some people to specialize in testing.

Success looks like whole team testing.

In addition to having a whole-team idea of success, many of the practices we applied are considered unorthodox - resulting from group of people already working well together and building that forward. With the research done at F-Secure and the external researchers, some things we did and did not do were considered to not match what had been written about test automation improvement and success in existing literature.

Particularly the organic nature of groups sharing ideas with a voluntary participation - enthusiastic participation even - seemed to be somewhat of a puzzle.

And success shows in other things as well. These we could collect at time of writing the article. The pink ones are from F-Secure, and I sampled the one team I spent most time with in the last two years at Vaisala as a comparison point.

Doing particularly well is still something I attribute more to my past team at F-Secure than any of the teams I work with now. We are still building a co-ownership culture and it takes time to root in fully in sustainable behaviors that remain when I am gone.

Now we have addressed the success for what we considered to be good, and it's time to discuss more on the why - or rather, seek the practices and ideas that seemed to help us in being more successful. Both of my cases are product development, and expectations of long term commitment to the product is a foundational belief. But what about the practices?

With the research work at F-Secure, we identified many practices that were considered factors for success. And with. the stars I overlaid on the F-Secure research results, I show that I think these are also factors I now recognise for success at Vaisala.

There is one we seem to need more work on in particular - the internal open source mindset. Personally I am undecided on the assets within the team only vs. shared assets in testing across teams, and with microservices the first may be more correct approach and it leaves learning on test automation as something within the team, not across the teams.

The only one I don't yet see at Vaisala is telemetry, and it was the last steps at F-Secure so it may just be a step ahead of us.

Since you can read about these practices in the published article, I want to pick 5 things that I did not discuss back then, that I think we should discuss today on how to become successful in automation.

First, the language of choice for test automation matters. While the trends of the world suggest "low code automation" or "special languages for testing" like Robot Framework so that we can ease manual testers into automation, the past manual testers are smart people and can learn programming. The idea of giving them tools that leave them to operate different tools than the rest of the team feels off to me.

A factor of success to co-owning sustainable test automation requires it to be build on a shared general purpose programming language. Removing Robot Framework has worked for me. Training Robot Framework to developers has worked also, and some developers emphasize they can write code in any language. At the same time, watching these people perform testing tasks with RF vs. Python, we get much more done in the latter. As we should know, writing code is not just writing it, it is also debugging it, and finding the ways of getting the right things in.

We built tests for a tool with pytest + Selenium and page objects in a fraction of a time compared to having tried the same with Robot Framework + Selenium earlier. IDE-support is that powerful.

Factor to success: Choose a general purpose programming language the team is already on. It means no single shared language for all things testing in your organization, and you can live with that. The other dimension is more important.

Second, learn to talk numbers. I had not done this at F-Secure, but I think it is essential at the part of the journey we are on at Vaisala.

While what I call contemporary exploratory testing was a de-facto way of thinking about testing at F-Secure in that one product I was in, Vaisala has more work in this space. And it helps to frame work as Everything that does not need to be automated gets done while automating to have good testing done and good automation left behind.

Showing in numbers where this is not true is good. Showing percentages of epics without automation. Showing percentages of automation failing and inviting us to explore, but late, with already red results in master. Showing the amount of work the late failures take, and optimising it for smaller.

It's not about setting targets, its about understanding where you are.

Third, we need to remember the principle of nothing changes if you change nothing. There are a lot of reasons for people to analyze a lot resulting in little movement, and that often means we are not making best possible progress in learning. Learning happens by doing, and continuous flow of small changes helps us with that.

Sounds like contemporary exploratory testing - we can't separate the test design from the test implementation, even when we are automating. We learn about the design when we implement it. And learning is essential.

Showing that with tools like Gource have been a good one for me.

Fourth practice is about a surprise I have learned testing for a release. We can choose to not run a single manual test case for release testing and rely on whatever tests we did while implementing the features. We can accept the only things we reverify at release timeframe are ones in automation.

We can choose to do continuous releases without test automation like I did some 7 years ago in yet another organization. Daily.

We can choose to release once a month running whatever tests we have now in automation. We can choose to extend our automation if this fails. And we got surprised on the idea that we needed to test for releases a lot less than we had previously designed.

We do follow the changes we make since last release on the baseline, so no change goes untested. We just don't collate that work to release testing timeframe. And we intertwine manual and automation with contemporary exploratory testing.

Fifth and final practice I wanted to mention is pair and ensemble testing. Particularly in times of remote, share your screen when stuck on an error message - don't just send the error message to someone to decipher. Take it further than problems, co-create code by sharing screen. Pair is two, Ensemble is 3 or more people.

I have had really positive experiences getting started with for example Selenium tests by creating first ones in an ensemble, the least knowledgeable starting at keyboard following words of most knowledgeable, and becoming knowledgable one code line at a time as we rotate who is on the keyboard.

I included here a reference for an ensemble testing session at the conference the day before. Watching some of that unfold reminded me that we choose to address some things and leave others out, particularly the printing of lines is something I have personally learned in ensemble testing that I can avoid with better use of debugging tools. It made me a better tester.

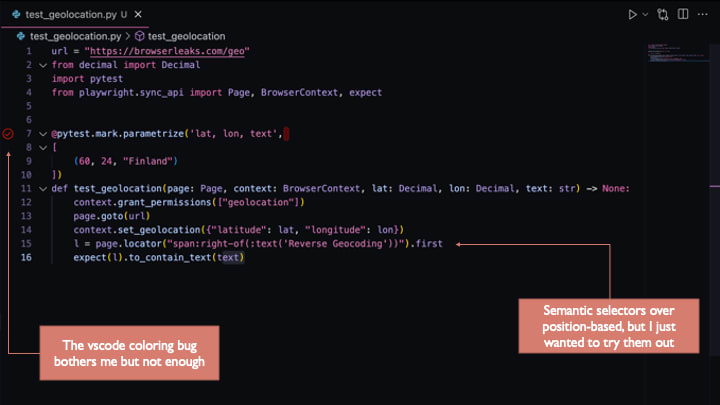

It does not matter what tools we use, here's an ensembled example of the same thing from another session with Playwright. Even with this one you can pick on the choices like using location-based selectors (a feature also made available with Selenium 4) but still knowing you should opt for semantic selectors. Or noticing bugs in your tools of choice (this time VSCode showing a red pass).

While I chose five specific patterns to success with whole-team test automation, these all come together to an idea I call contemporary exploratory testing.

Everything that does not need to be automated gets done while automating.

You can't automate well without exploring. You can't explore well without automating.

That can be true if you know how to test and automate, and learn while you do the two. There is no manual and automated testing. There's a lot of manual things we do resulting in the best automation we can keep around.

Improved understanding of success is that it does not rely on single people. It is built into the whole teams. And not as service an individual provides for their team, but as a service everyone helps with and contributes in within what they can do today, growing to what they can do tomorrow.

I enjoy connecting with people, and love a good conversation. You may notice I like my work. I also like talking about themes related to my work. I started speaking to get people to talk to me. I talk back, and I invite you all on a journey to figure out how we explore our way into a better place for software creators and consumers.

I’m happy to connect on LinkedIn, and write my notes publicly on Twitter.

Top comments (0)