This is a crosspost from my blog mokacoding.com.

In this excellent episode of The Ruby Testing Podcast host Jason Swett discusses TDD and refactoring with Chris Toomey. Among other things, they draw a comparison between coding and cooking. A clean workspace is valuable in both professions.

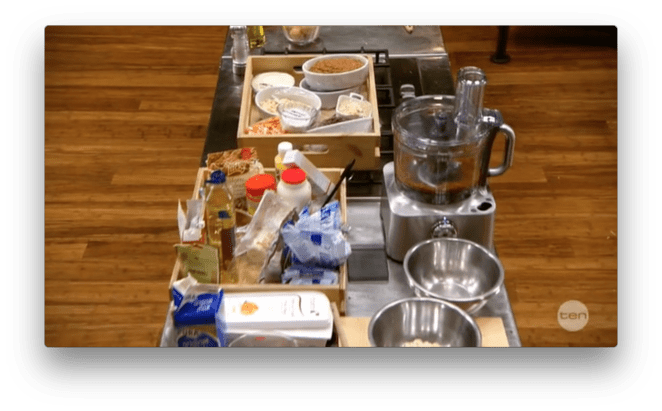

The cooking metaphor resonates with me. My wife is a huge fan of cooking shows, so I've watched my fair share of them. Her favorite is MasterChef Australia. In the 2015 season finale, the last challenge for the two contestants was to reproduce a dessert designed by Heston Blumenthal.

During the test Heston walked over to finalist Georgia, who was starting to feel the pressure, and told her:

If you are not careful you're gonna end up be so cluttered that in the end you'll get caught up.

Georgia ended up losing the finale, her dish not at the same level as the other contestant, Billie. It's interesting to note that throughout the season and in particular during this final hurdle Billie was calm and organized. She made such an impression on Heston that he offered her a job on the spot, at the end of the episode.

Earlier on in the same Master Chef season Anna Poloyviou touched on the value of tidiness too.

During her pressure test challenge she kept pushing contestant Fiona to keep her bench clean:

It's not for me, is for you. Because it will affect your end product.

Fiona then justified herself saying:

Of course my bench is a mess, but I don't really have time to clean, I need to assemble the cake.

Fiona lost the challenge and went home.

Compare Fiona and Georgia with chef and MasterChef judge Gary Mehigan. When Gary cooks in one of the show master classes you can see him almost compulsively wiping up the bench, keeping it spotless.

Keep your bench clean!

The keep your bench clean rule is as valid when building software as it is when cooking dishes.

If your codebase is messy and cluttered, getting stuff done will be harder and harder. You'll spend time deciphering unreadable code, scrolling through endless files, browsing deep folder hierarchies. The same goes for your workstation. If your computer and desk are not tidy all the unnecessary things on them will draw on your attention and make it harder to find what you're looking for.

How can we keep our benches clean? It's a matter of small little habits. Here's some.

Cleanup first

At some point during Jason and Chris' culinary trip in the podcast, Chris mentions how he likes the mise en place cooking technique of preparing all the ingredients for a dish beforehand and have them ready each in their bowl.

When working on code, spending the time to clean up the areas you are going to touch before starting the feature work can save you time afterward. In Kent Beck's words "for each desired change, make the change easy (warning: this may be hard), then make the easy change."

Delete unused code when you find it

Unused code slows you down. Keeping unused code does to your project the same thing never throwing away anything does to your house, it makes it a messy place.

As soon as you notice unused or unnecessary code, you should delete it.

This is sometimes referred to as the boy scout rule, "always leave the campground cleaner than you found it." If you find a mess on the ground, you clean it up regardless of who might have made the mess.

When you remove unused code, you should perform the change in a dedicated commit, which brings us to the next tip.

Make small atomic commits

An atomic commit is one that does one single thing, with the code building and the tests passing. Atomic commits are great because they leave the codebase in a stable state. If you checkout one you'll be able to run the software immediately.

They are also straightforward to revert because the changes they made are isolated and self-contained.

On top of keeping your commit atomic try to keep them small as well.

Commits are cheap to make and to store. Being able to look at a commit and fit everything it does in your mind is much more valuable.

A variable rename can be a dedicated commit.

An indentation fix can be a dedicated commit.

A typo fix can be a dedicated commit.

Keeping those cleanup changes in dedicated commits also makes it easier to look at the diff of the other commits in a pull request, because they will be free from that noise.

Never commit commented code

Commented code clutters your codebase for no reason. It makes it harder to scroll through files and can create false positives when doing text searches.

If an inner voice whispers "you might need it later," scream "YAGNI" at it.

Besides, even if you delete that code, Git will remember it. Instead of commenting code, delete it in a dedicated atomic commit, with a clear title and a message explaining why you removed it. If you really feel like you will need to use it again tag the commit, or write its SHA somewhere.

Git will save it for you until then.

Keep your methods, classes, and files short

In Clean Code Uncle Bob writes:

The first rule of functions is that they should be small. The second rule of functions is that they should be smaller than that.

He goes over recommending that functions "should hardly ever be 20 lines long."

Clean Code was written with Java in mind. Depending on the language you work with 20 lines might be very long. In fact, some Ruby developers follow even stricter rules that Sandi Metz once recommended to a team trying to get on top of their legacy codebase.

- Classes can be no longer than one hundred lines of code.

- Methods can be no longer than five lines of code.

- Pass no more than four parameters into a method. Hash options are parameters.

- Controllers can instantiate only one object. Therefore, views can only know about one instance variable and views should only send messages to that object (

@object.collaborator.valueis not allowed).

The benefit of small functions and objects is that they are easier to read, reason about, and move around. I'd rather jump through a lot of small functions that are easier to work with than taxing my brain trying to hold dozens of lines of code in its working memory while reading through a single long one.

Use a style guide

Having the code follow a style guide makes it easier to both write and read. Developers don't have to think about things like where to put braces, or how many newlines should be used to separate blocks of code.

The more homogeneous the style of a codebase is, the easier it will be to work with it. If all the code looks the same, you won't have to spend time moving between different styles but will be able to get straight to the task of understanding what the code does.

Style guides are perfect for this. They also remove the need for having conversations about how the code looks like during code reviews. If it doesn't follow the style guide, it should be changed. If a developer thinks a rule in the style guide can be improved, they can open a PR making a case for it in the style guide itself.

Most programming languages have linters that can automate the process of checking in the code follows specific style rules. Tools like Hound CI can automatically comment in pull request when style guide rules are violated.

You know what's even better than integrating a linter in your workflow?

Using an automated formatter, like Prettier. This kind of tools takes the code you wrote and re-formats it by applying a given style guide.

I love linters and formatters because they help me stick to a style guide without having to remember it all in one go. I don't trust my brain, the more I can offload from it the better.

Looking after the codebase is as essential for software developers as keeping the bench clean is for chefs. The best chefs a rigorous about the state of their workplace. We should adopt the same discipline.

Software developers have an extra challenge that people working in the kitchen don't. A messy bench is apparent to the naked eye, a messy codebase doesn't immediately translate to a messy interface for the users. It's harder to grasp the value of keeping code clean. Yet, over time, an untidy codebase will be as catastrophic for you as the messy benches were for Fiona and Georgia.

This article war originally written on August 2015, it's been edited and updated since then.

Top comments (0)