If you have never heard of Promises in JavaScript, chances are that you have experienced what is often termed as callback hell. Callback hell is referring to the situation wherein you end up having nested callbacks to the extent that the readability of your code is severely hampered.

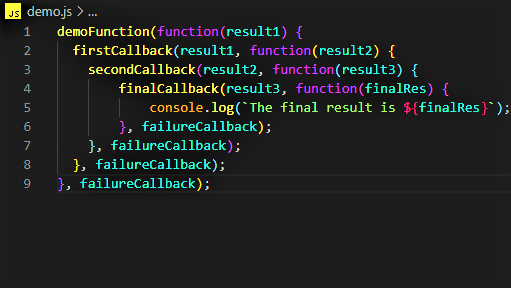

If you have never experienced callback hell, let me give you a glimpse of what it looks like. Brace yourself and try to understand what the following piece of code is trying accomplish!

Okay, to be fair, this might have been a slightly exaggerated example. But, it proves the point that attempting to nest callbacks can drastically reduce the readability of your code.

In case you are wondering as to why you should bother about the readability of the code you write, then take a look at the following article which provides an in-depth answer to the query.

Psychology of Code Readability. By no means should this be regarded as… | by Egon Elbre | Medium

Egon Elbre ・ ・

Medium

Medium

Medium

Medium

Now that you realize that callback hell is notorious, let’s also briefly take a look at what causes a developer to fall into this trap in the first place.

The main reason we use callbacks is to handle asynchronous tasks. Many a times, this can be because we need to make an API call, receive the response, convert it to JSON, use this data to make another API call and so on. This can seem like a problem that’s innate to JavaScript, because the nature of these API calls in asynchronous by default, and there seems to no workaround.

This is where JavaScript Promises come into the picture, because it is a native JavaScript feature released as part of ES6, meant to be used to avoid callback hell, without having to break up the chain of API calls into different functions.

A Promise is an object that can be returned synchronously, after the completion of a chain of asynchronous tasks. This object can be in one of the following 3 states:

Fulfilled: This means that the asynchronous tasks did not throw any error, and that all of them have been completed successfully.

Rejected: This means that one or more tasks has failed to execute as expected, and an error has been thrown.

Pending: This is like an intermediate state, wherein the Promise has neither been fulfilled nor been rejected.

We say that a Promise is settled, if it is not in a pending state. This means that a Promise is settled even if it is in a rejected state.

Promises can help us avoid callback hell, because they can be chained using .then() any number of times.

.then() is non-blocking code. This means that the sequence of callback functions can run synchronously, as long the Promises are fulfilled at every stage of the asynchronous task.

This way, no matter how many asynchronous tasks there need to be, all we need is a Promise based approach to deal with them!

This can work because instead of immediately returning the final value, the asynchronous task returns a Promise to supply the value at some point in the future. Since we have no code that blocks this operation, all the asynchronous tasks can take place as required, and the Promise that is returned will reflect whether or not they failed.

By now, you understand what a Promise is. But how do you use them? Let’s deal with that in this section.

Consider an example which uses plain old callbacks, which we can then convert to a Promise based approach.

As you can see, although this is a contrived example, it is pretty tricky to follow the chain of function calls as the number of callbacks increases. Now, if we chain all our callbacks to the returned promise itself, we can end up with the following Promise chain.

Here, we assume that the demoFunction returns a Promise after it is invoked. This Promise eventually evaluates to either a valid result, or an error. In case the Promise is fulfilled, the .then() statement is executed.

It is important to note that every .then() returns a new Promise. So, when the demoFunction returns a Promise, the resolved value is result1 which is used to invoke the next function in the chain, the firstCallback(). This continues until the final callback is invoked.

In case any of the Promises get rejected, it means that an error was thrown by one of the callbacks. In that case, the remaining .then() statements are short-circuited and the .catch() statement is executed.

You may notice that a single .catch() is needed to act as a error fallback, whereas in the previous version of the code, we had to provide failureCallback function as a fallback error handler, to each callback function call.

This way, you can easily convert a series of nested callbacks into a Promise chain.

Until now we have learnt a new way to deal with callbacks using Promises. But we haven’t discussed where we get these Promises from. In this section, you can learn how to convert any function, such that it returns a Promise which can be chained to a list of .then() statements.

Consider the following example wherein we have a function which doesn’t return a Promise, hence it cannot be included in a Promise chain yet.

setTimeout(() => callbackFunc("5 seconds passed"), 5\*1000);

Here, although the callbackFunc has a very low chance of throwing an error, if it does do so, we have no way to catch the error.

In order to convert this function into one that returns a Promise, we can use the new keyword as follow:

const wait = ms => new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(resolve, ms);

};

wait(5*1000)

.then(() => callbackFunc("5 seconds"))

.catch(failureCallback);

Here, wait represents a function which returns a new Promise every time it’s invoked. We can do so using the Promise constructor, which creates a new Promise object. Hence, when wait is invoked by passing a parameter indicating the duration for setTimeout , it returns a Promise.

Once the Promise reaches the fulfilled state, the function associated with resolve i.e, callbackFunc is invoked. If the Promise is rejected, then the failCallback is executed.

To further understand how to create your own Promises, you can go through this article, which provides a more complex example to do so.

The best resource to dive deeper into the various instance methods in the Promise constructor, is the MDN Docs.

Although the approach laid out in this article is a simple alternative to nested callbacks, a newer version of JavaScript (EcmaScript 2017 or ES8) also has a feature to deal with callback hell!

In case you want to look into this feature called async & await, you can go through the following article. Although it is stated as a brand new feature, it is actually just syntactic sugar over the concept of Promises discussed in this article! So, in case you understand the concept of Promises, the ES8 feature of async & await is pretty easy to comprehend.

Javascript — ES8 Introducing `async/await` Functions | by Ben Garrison | Medium

Ben Garrison ・ ・

Medium

Medium

Medium

Medium

Hopefully, now that you are armed with Promises, you can successfully avoid falling prey to callback hell, the next time you are tasked with handling a bunch of callback functions!

Top comments (0)