I thought I understood Ruby's Module class, but nope. While reading Jeremy Evans' Polished Ruby Programming, I looked deeper and found some confusing things.

At first glance, it seems clear. The docs: "A Module is a collection of methods and constants." That's fair. Kinda like traits in PHP, or the general programming concept of mixins. So you can declare a module:

module Greets

GREETING = "Hello"

def greet

GREETING

end

end

and add it to a class to get access to that functionality:

class Bob

include Greets

end

Bob::GREETING # => "Hello"

Bob.new.greet # => "Hello"

That part isn't so hard (although I still occasionally have to remind myself of the difference between include, extend, and prepend).

But what bugs me is more about the Module class than how a module behaves. For starters, all classes in Ruby inherit from Module ¹:

class X

end

X.is_a?(Module) # => true

X.class.ancestors # => [Class, Module, Object, Kernel, BasicObject]

That's alright, but conceptually doesn't this mean that all classes are modules. Liskov substitution, yes?

This means we should be able to include, extend, and prepend a class onto another, just like we would with a module.

class Dog

def bark

"Woof!"

end

end

class Rover

include Dog

end

Rover.new.bark

./test.rb:24:in `include': wrong argument type Class (expected Module) (TypeError)

from ./test.rb:24:in `<class:Rover>'

from ./test.rb:23:in `<main>'

WTF. Classes are modules, but yet...not modules? Craziness number 1.

To be fair, Ruby isn't very big on Liskov substitution. And, as Jeremy Evans, points out, if a subclass needs to act exactly like its parent, what's the point of making a new class?

But, even acknowledging that, I have to conclude that Ruby's class hierarchy is a mess (but a mess that works). For instance, "everything is an object" sounds cool (and is very useful), but then every object in Ruby has a class. And every class is an object. Which means every class must have a class. And so on...

The effect of this is that, in Ruby, the class hierarchy never ends. Technically speaking, there is a root object. There's BasicObject, which Object inherits from, which Class then inherits from. But since BasicObject is a class, then it must also inherit from Class (which inherits from Object, which inherits from BaciObject, etc). So technically speaking, BasicObject inherits from itself! "I'm my own grandpa."

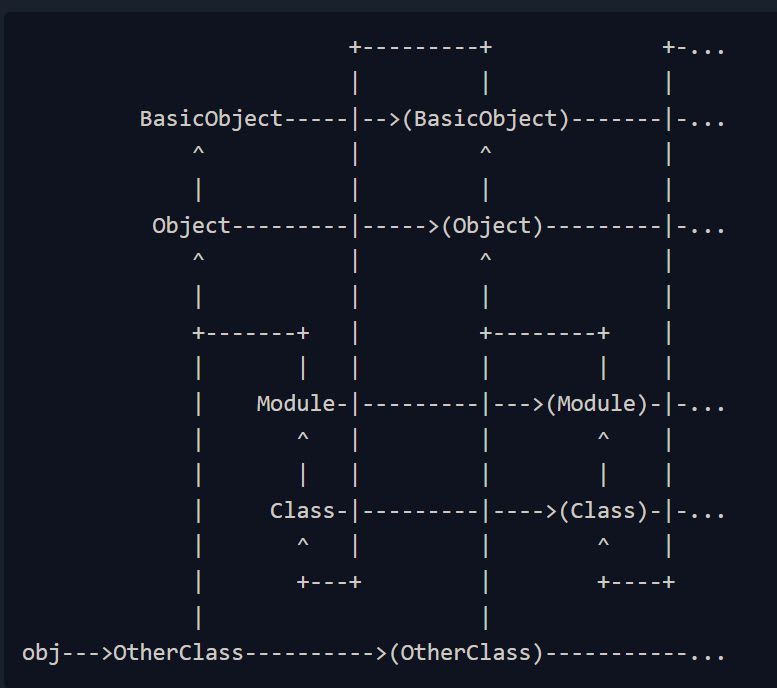

In fact, the documentation for Class has this diagram for a simple object's class hierarchy:

(This diagram includes singleton classes, aka metaclasses, but I'm ignoring them for today. They're a whole other thing to keep track of.)

Anyway, it all makes for a beautiful soup². Obviously, this was a design chosen with its tradeoffs, and things generally work fine—when walking up class hierarchies looking for a method, once you get to BasicObject, stop, because any further will be a cycle, but it's a bit funny. For the most part, you don't need to worry about it; it just gets weird when you try to explore the (almost) internals.

The other thing I find confusing about the Module class is the stuff in it. Module has a lot of instance methods that are...unrelated to being a module. Remember that the doc itself says a module is a "collection of constants and methods". In regular OOP then, the parent class of all modules, Module, should have functionality for this, while the parent class of classes, Class, should have functionality for class-related stuff. But yet, methods like class_variable_get and remove_class_variable are in Module, not in Class. You also have class_eval and class_exec, which are aliases of module_eval and module_exec, but still—the aliases could have been defined in Class.

So why is this? Well, for one, Module is higher in the hierarchy than Class (every class is a Module, but modules are not classes). So methods like define_method have to be in Module, otherwise modules wouldn't be able to define methods (sorta; you can still use def). In fact, one thing I've learnt from this exercise is that, while in most OOP languages the unit for holding methods and variables is a class, in Ruby, it's a module.

Also, methods like remove_class_variable have to be in Module, rather than Class, because modules can define class variables, which become part of any class they're included in:

module X

@@foo = 5

end

X.is_a?(Class) # => false

X.class_variable_get(:@@foo) # => 5

class Y

include X

end

Y.class_variable_get(:@@foo) # => 5

And the rest of it is mistakes, IMO. Theclass_eval alias should have been defined in Class, at least for naming consistency.

My conclusion: Ruby doesn't care too much about strict OOP. (I know Ruby is based more around message passing and structural typing, but considering they try to follow the class thing, I initially expected more.) It gets messy in places, but Ruby makes it work in such a way that you wouldn't normally notice.

Notes

¹ Aside: One thing I often forget in Ruby is that an object's inheritance chain is gotten from .class.ancestors, not .ancestors. This can seem obvious at first (regular objects don't have the .ancestors method), but it's easy to mix it up because classes (and everything) are objects, too. The key thing to remember is that running .ancestors on a class gives you the inheritance chain of the class' instances, not of the class itself.

class Parent

end

class Child < Parent

end

Child.ancestors # => [Child, Parent, Object, Kernel, BasicObject]

Child.is_a?(Parent) # => false

Child.class.ancestors # => [Class, Module, Object, Kernel, BasicObject]

It's kinda like JavaScript's prototype chain. SomeClass.prototype is the prototype that SomeClass' children will get, not the prototype SomeClass inherits from.

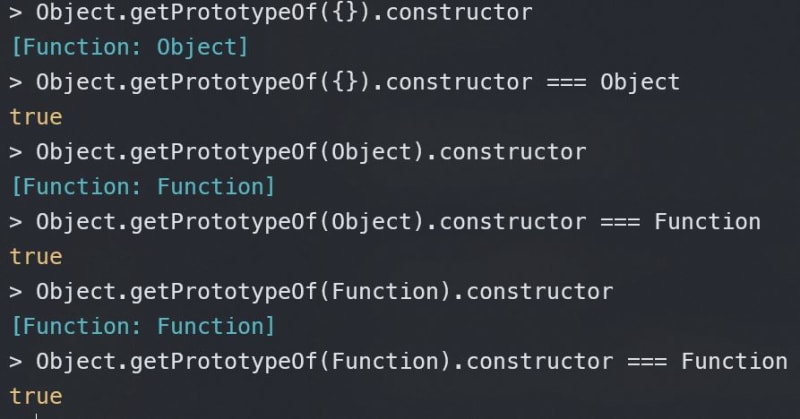

² JavaScript's object model is also something of a mess, but that's because of prototype shenanigans. In JS, most things are objects, but they don't have to be classes. In fact, classes are just syntax sugar for constructor functions, so we can completely ignore them. There's the Object class, which most objects inherit from. But while writing this, I found myself asking what Object inherits from:

Turns out Function is the real root object, and it also inherits from itself (directly). Which makes me wonder, is it possible to define an object-based (not just OOP) language without running into a cycle at some point? Probably not. 🤔

Top comments (0)