At first glance, I made the same assumption that I see many other people making - that Temporal executes their workflow code. As I looked deeper, I learned that the execution model of Temporal is actually more interesting, and more powerful. I figured I should write a post describing the execution model at a high level. Hopefully, this will help give people a starting mental model for Temporal’s core architecture.

I call it: Inversion of Execution.

Disclaimer.

I am not saying that Temporal was first to implement this kind of execution model. It wasn't. There were earlier products that used similar ideas. I'll leave the genealogy research for an aspiring PhD student to perform. Somebody probably wrote a paper laying all this out back in the 1970s.

Architecture

Temporal is a workflow engine. That made me immediately think about how I would deploy my workflow (application) code to it, how it ensures security, performance isolation, versioning, and all other concerns that accompany running somebody else's code. I see many people making the same set of assumptions and having similar concerns, in the beginning of their Temporal journey.

In reality, Temporal doesn't execute application code at all. It "only" orchestrates execution of your code in order to drive workflows to completion. Application code leverages Temporal via the client SDKs in such a way that it's not even immediately apparent where the Server gets into the picture.

In other words, there is an Inversion of the standard Execution model we are used to.

That's how the analogy with Inversion of Control came to my mind. Instead of injecting dependencies, Temporal "injects" steps of execution (known as tasks) into application code. Temporal can run (and, if necessary, rerun) those steps to overcome intermittent failures of outgoing calls and to recover from infrastructure failures. There are two kinds of tasks in Temporal: Workflow Tasks and Activity Tasks. They have different purposes and use separate persistent queues for reliability and scalability.

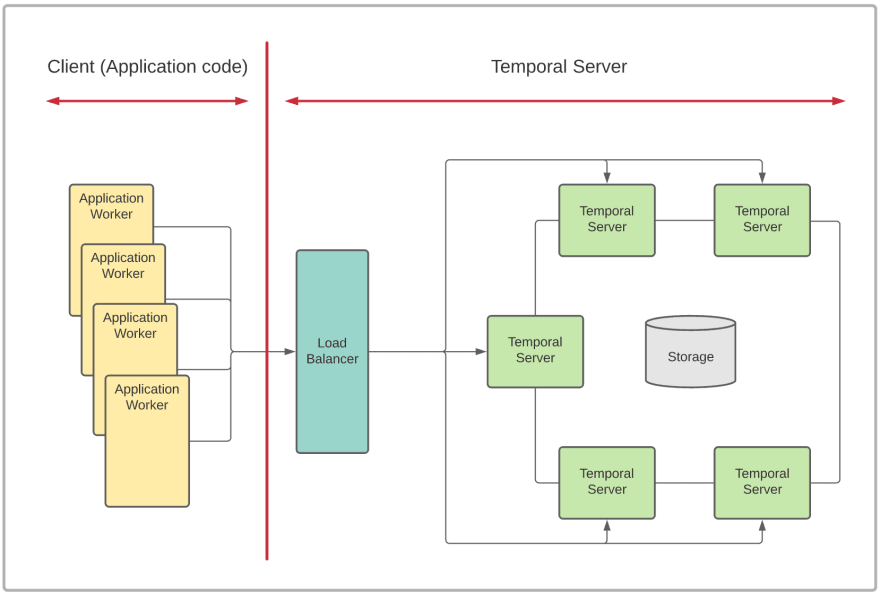

This is the topology of a typical Temporal-based system:

Temporal Server is usually run as a cluster of servers for reliability and scalability. The Server is backed by a database for persisting state.

None of your application code ever runs on the server. Instead, application logic runs on the client side of the picture. It is also usually organized as a cluster of Worker Processes, for scalable execution.

The umbilical cord connecting client to the server is the Client Runtime piece (a.k.a. SDK). Don’t underestimate it based on the name. Unlike typical SDKs that are mostly language-specific wrappers around a set of server APIs, Temporal SDKs do much much more than that. They contain the complex machinery that hides all interactions with the server and handle the non-trivial process of reconstructing client state after a failure. The goal is to free the business logic from all of that complexity, and enable the application code to be concise and easy to write.

Bank Transfer Example

Let's look in more detail at how Temporal actually executes workflows, using the canonical example of transferring a sum of money from one account to another. While a real financial transaction may involve many steps, we will keep it simple and just talk about performing one debit and one credit operation. That should be enough for showing the mechanics of Temporal.

A workflow like this is typically started by a client process, for example, a web frontend, with a single gRPC call to the server through the SDK.

Go:

we, err := client.ExecuteWorkflow(context, workflowOptions, money.TransferFunds, params)

Java:

WorkflowClient.start(transferWorkflow::transfer, from, to, reference, amountCents);

If this call succeeds, the money transfer workflow has been accepted by Temporal Server. Even if the client process were to crash immediately after that, Temporal will drive execution of the workflow to eventual completion or failure.

Under the covers, Temporal Server already persisted a record of the workflow with its arguments, options, and unique execution ID. As part of that transaction, it puts a Workflow Task into the corresponding Workflow Task Queue. This task contains a WorkflowExecutionStarted event as a first event in the workflow’s history.

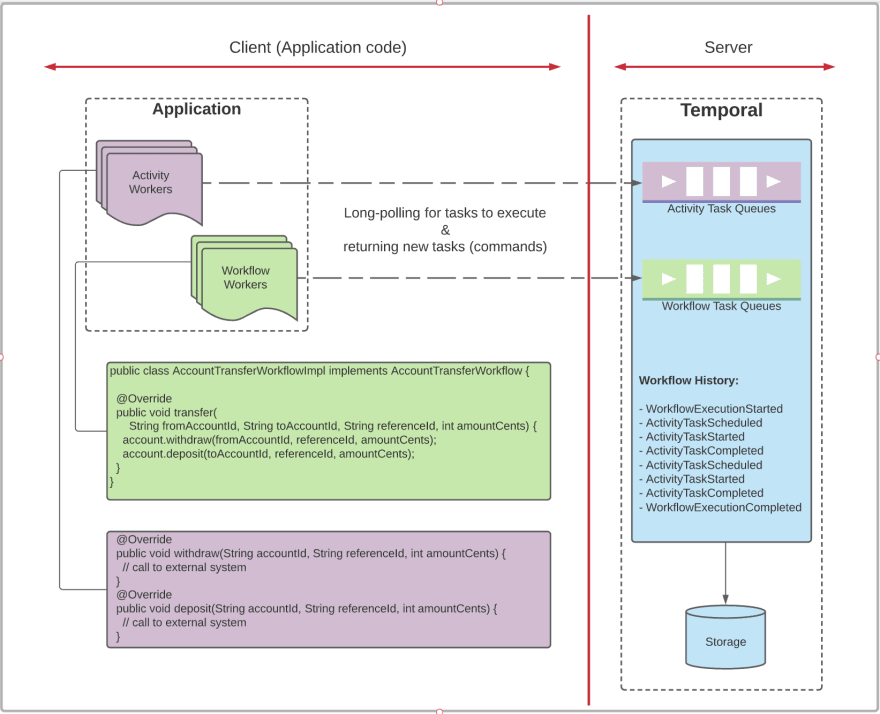

Workflow implementation code (in our example transferWorkflow::transfer) is compiled into a Workflow Worker. When a Workflow Worker process starts, it connects to Temporal Server via Temporal Client Runtime (a.k.a. Temporal SDK) and starts long-polling the Workflow Task Queue for tasks to execute. That's how it receives the Workflow Task with a WorkflowExecutionStarted event inside from the server.

Note that the Workflow Worker didn't even have to be up and connected to the Server when the workflow was submitted by the client. It could connect later or experience a temporary outage. It doesn't matter; once the application worker connects, it will pull the task from the queue and start executing it.

A Workflow Worker (there's usually more than one worker process running for redundancy and scalability) receives the initial Workflow Task that contains a WorkflowExecutionStarted event as the first event of the workflow history. This event includes a workflowType.name field that indicates which workflow type Client Runtime needs to invoke. Runtime performs a lookup in the map of registered workflow types and calls the corresponding application function that starts actual execution of the workflow logic.

Workflow code defines a sequence of steps, not necessarily linear, that need to be executed for a workflow to complete. Some of these steps are actions that involve communication with external systems. In our example they are Withdraw and Deposit functions on the two given accounts. Such functions are referred to in Temporal as Activities. They are the second most important concept in Temporal after Workflows.

Workflow code invokes an Activity by calling workflow.ExecuteActivity function in case of Go:

future := workflow.ExecuteActivity(context, money.DebitFunds, params)

or by invoking Activity stubs in case of Java:

@Override

public void transfer(

String fromAccountId, String toAccountId, String referenceId, int amountCents) {

account.withdraw(fromAccountId, referenceId, amountCents);

account.deposit(toAccountId, referenceId, amountCents);

}

Execution of Activities is tracked and orchestrated by Temporal Server, very similar to how Workflow Tasks are handled. When account.withdraw() is called in our example, Client Runtime sends a command to the server behind the scenes - a request to execute an Activity of the given type with the provided arguments. This request gets recorded in the Workflow History as an ActivityTaskScheduled event, and the corresponding Activity Task gets added to the Activity Task Queue. These updates are performed transactionally, so that the Workflow History and Task Queues are always in sync, and no task can be lost.

The Activity Task then gets picked up and executed by one of the Activity Workers long-polling the Activity Task Queue. Activity Workers are conceptually similar to Workflow Workers, and are often combined into a single Worker process. Even different Workflow and Activity types can be isolated into their own Worker processes, for security, performance, or other concerns.

The important part here to stress is that Temporal Server records the intent to execute application steps before their actual execution and then records the results they produced after they complete. This makes it possible to resume execution of application logic after any failure, from the step that previously failed. These recorded application steps, Workflow and Activity Tasks, are then passed to Application Workers for execution. Hence, the notion of Inversion of Execution - an application process is told by Temporal Server (via the Client Runtime) what tasks to execute when.

Benefits

This model of execution brings a number of benefits.

1. Reliability

Each step of a workflow execution is recorded first with all its inputs, so that the workflow can resume from where it left off after any failure or even a complete shutdown of the system. When an Application Worker starts after a failure or a planned update and receives a task to resume execution of a workflow from a particular step (next after the last successfully executed), the Client Runtime deterministically replays execution of the Workflow Tasks that already succeeded, so that it can continue as if there was no failure or restart. Interestingly enough, the application code doesn’t even know if it’s executing a Task that previously failed or running it for the first time or replaying a task that already succeeded. That's why the Temporal programming model is often referred to as Fault-Oblivious - because application code indeed can stay mostly unaware of recoverable failures.

2. Security

The separation of concerns provided by the Inversion of Execution approach where Temporal only handles orchestration of execution without actually executing application code, makes it possible for applications to run with zero trust of Temporal. Every payload (arguments and results) of Workflows and Activities can be encrypted on the Application Worker side (via the Data Converter feature), so that Temporal Server has no way of knowing what application is doing and what data it is operating on. This clean separation makes security and compliance reviews much easier to conduct because the zero trust story is very compelling.

3. Scalability

Execution of each workflow is independent and logically isolated from all other workflows in the system. Temporal is only responsible for recording execution steps and communicating with application workers. Because of that, Temporal Servers are relatively easy to scale out by adding more servers and redistributing responsibilities for different workflow ID ranges (shards) between them. Of course, storage needs to be able to scale up or, better, out accordingly.

Scalability is made easier because Temporal is not responsible for hosting and executing application code, and only needs to scale with the rate of execution tasks being generated and recorded. Scalability of application code (workers) is handled separately, and such clear separation makes it easier to find out and eliminate bottlenecks.

Is this a queueing system?

If you think that this looks like a task queuing system, I wouldn’t say you are wrong. Temporal can be viewed as a specialized queue of execution. In a way. But if you ever implemented a high-throughput reliable message processing system that used queues, I'm sure you’ve had to solve a number of non-trivial problems in order to achieve good performance with strong consistency. Retries and backoff in case of failures, deduplication of reprocessed messages, how to handle a failing or slow message that is blocking a queue partition, dead-letter queues and violation of ordering guarantees, etc. These are hard problems to solve.

Temporal provides an opinionated set of solutions to these problems, and raises the level of abstraction, so that application developers don't have to think about them. Inversion of Execution is one of the core opinionated decisions, and I hope this post helps you see why.

Top comments (0)