When we start learning a new language, we forget to understand what happens when we execute our lines of code. We want to see our printed output on the console, or see its actions running, and we forget to understand how this is possible. Understanding how languages work internally will allow us to advance more quickly in their learning. So today, I want to summarize how JavaScript works behind the scenes.

How browser execute our code?

Doing a review of what I talked about in my previous post Java vs Javascript, let's continue to delve into the execution of our code.

JavaScript is always hosted in some environment. That environment is almost always a browser, or as in the case of NodeJS it can be on a server. Inside this environment there is a engine that will execute our code. This engine is different in each browser: Google's V8 for Chrome and Opera, Mozilla's Gecko and SpiderMonkey for Firefox etc...

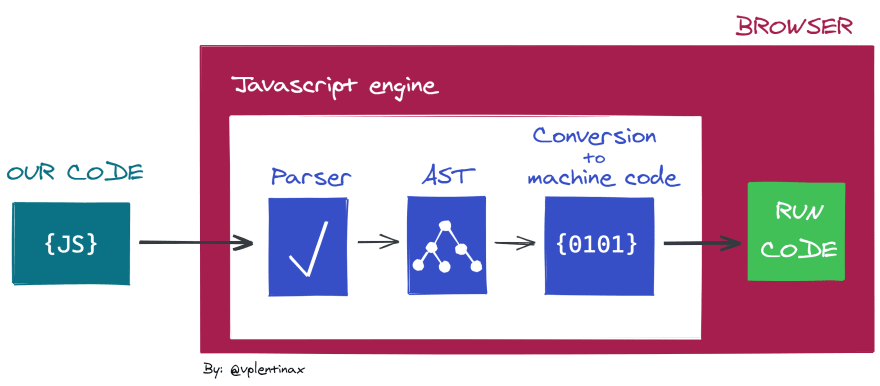

The first thing that happens inside the browser engine is that our code is parsed by a parser, which basically reads our code line by line and check if the syntax of the code we gave you it's correct. This happens because the parser knows the syntactic rules of Javascript so that the code is correct and valid. If it encounters an error, it will stop running and It will throw that error.

If our code is correct, the parser generates a structure known as AST or Abstract SyntaxTree. The syntax is "abstract" in the sense that it does not represent all the details that appear in the actual syntax, but only the structural or content-related details. This structure is translated into machine code and it is at this moment that the execution of our program actually occurs.

Context execution

As I mentioned in the previous post, when we talk about JavaScript code execution, we need to keep in mind the execution stack and scope.

When the code is executed, the JavaScript interpreter in a browser takes the code as a single thread, this means that only one thing can happen at a time, and appends these actions or events into queues, in what is called the execution stack.

Who creates the contexts?

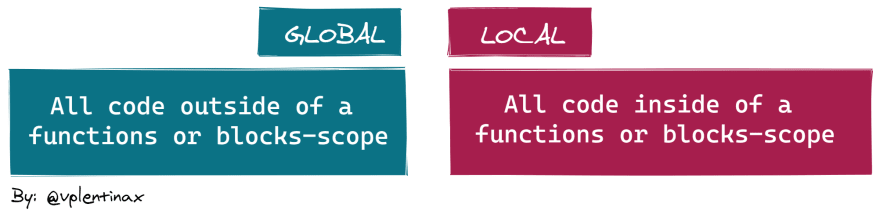

I'm not going to give a great explanation about this because basically the contexts in the browser are created by the functions and, in some cases, by the called blocks-scope ({let / const}). Contexts are stored in objects that also differ in global and local. These contexts in turn create a scope.

Global Context and Local Context

The execution context can be defined as the scope in which the current code is being evaluated. When the code is run the first time, the browser automatically creates the Global Execution Context. We can define the global context as that code that is not inside a function or inside blocks-scope.

The local context is created when a declared function is called. When the synchronous execution flow enters that function to execute it's instructions, it creates it's local context for that function call.

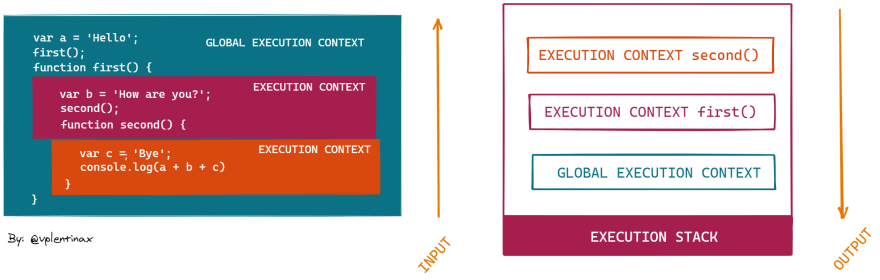

The global context is located in the first position from bottom to top in the execution stack. Every time a new context is created when a function is called, this placed at the top of the queue. Once it's executed, they are eliminated from top to bottom.

Context Object

I mentioned that contexts are stored in objects. These are known as context objects. This does not happen as simply as it's to pronounce it. Let's see it:

Creation of the variable object

- Argument object is created, which stores all arguments (if any) in a function.

- The code is scanned for function and variable declarations and creates a property in the variable object (VO) that points to those functions and variables before execution. This process is known as hoisting.

Hoisting: Elevate functions and variables by making them available before execution, albeit in different ways:

- Functions: only those that are declared. It makes them fully available.

- Variables: makes them available but as undefined.

Scope Chain

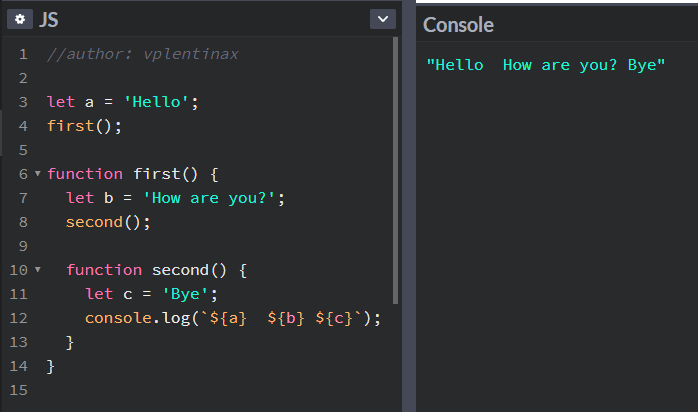

The scope answers the question: where can we access? Each new function call creates a new scope that makes what is defined in it accessible. Accessibility within that scope is defined by the lexical scope, which is practically the one that identifies the position of 'something' in the code. As the flow of execution is followed, a chain of scopes belonging to the object variable is created to finally create the context object.

If you come from a programming language like Java, you can conceptualize the scope as access modifiers (public, private, protected ...), since the scope is the ability to access from one place in our code to another. The scope is privacy. We will see it in practice with the code of the image that I have put as an explanation.

In the scope chain, the innermost function of the chain is placed in the first position from bottom to top, this implies that this function has access to all the functions that will be above it in the scope chain. For this reason, the execution is successful. But what would happen if we tried to call the function second() from the global scope?

The global scope cannot access the local scope of internal functions, as is second(). Let's see another example:

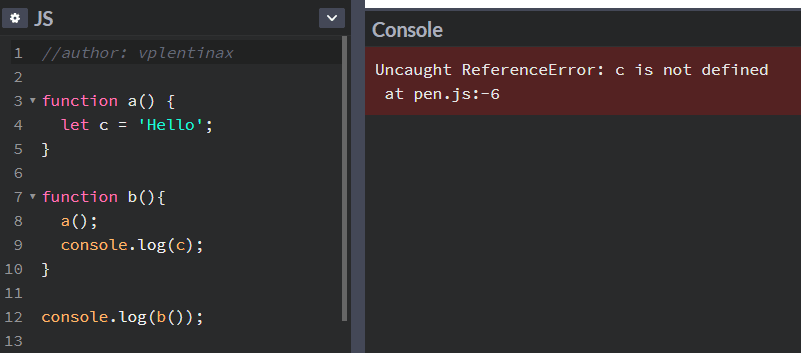

Although both functions are declared in the global scope, the b() function cannot access the local variables of a(). Simply put, the scope chain works like this:

Lexical Scope

Before we mentioned the lexical scope. This is best seen when we take the example of the bloks-scope and the declaration of variables ES5 (var).

Although both variables are declared within blocks ({}) within the lexical scope, the scope is only assigned to "let". This happens because the function declaration with "var" is not strict, and its scope is only assigned when it's lexical scope is inside a function. However, "let" is considered a block-scope just like "const", because when declared within blocks they generate their own local scope.

For this reason, many professionals in the field of programming believe that the correct concept is to literally define this scope when the "let" is declared inside blocks, such as those created with if conditionals. That is to say:

And not like this:

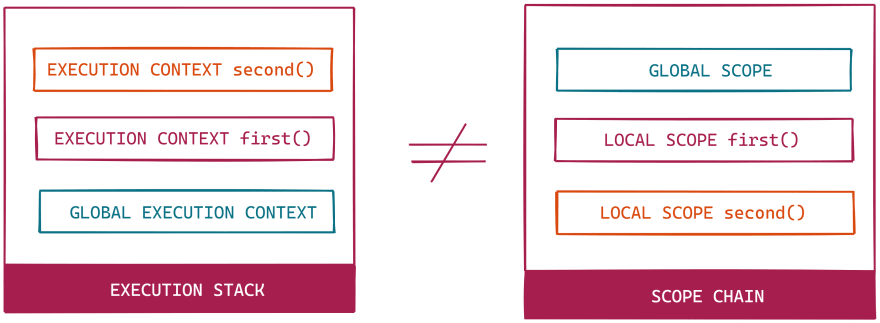

To finish this part of the process of creating the context object, I wanted to remember that we should not confuse the execution stack with the scope chain, both refer to different concepts as we have already seen.

The execution stack is how the function calls are placed inside the execution stack, storing their context, while the scope chain refers to the scope of accessibility existing between the different contexts.

Define the value of THIS

And to finish the first phase for creating the context object, you must assign a value to "this". This is the variable that will store each of the contexts.

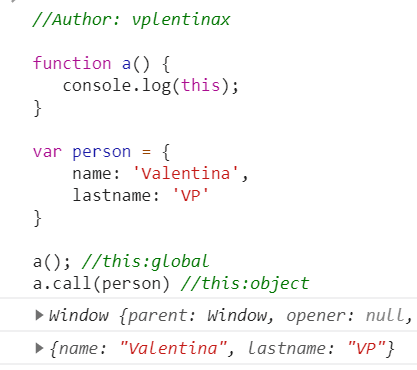

In a normal function call, this keyword simply points to the global object, which, in the browser's case, is the window object. In a method call this variable points to the object that calls the method. These values are not assigned until a function call is made where it's defined.

Once the call is made, "this" will take the context of the function where it was defined. Let's see it more clearly with this example on the console.

When the function is called for the first time, it takes the value of the global context that is window, while when calling it assigning a new local context created by the person object variable, "this" takes this new local context as value.

Execution code

In this way, the context object is created and goes to the second phase, which is the line-by-line execution of the code within each context until each function call ends and they are removed from the execution stack.

This has been an explanation of how the execution of our Javascript code would be visualized internally. I know the terms can be confusing, but I hope I was able to help you understand this process. See you soon!

If you want to read more about Javascript:

If you want to read about other topics:

Top comments (1)

100 %