This post is part of my miniseries, Declaring Variables in JavaScript.

Declaring Variables in JavaScript

Daniel Brady ・ Jan 20 '20 ・ 2 min read

If you've already read some of the sibling posts, you can skip straight to here.

CONTENTS

- The basics: declaring variables

- The specifics: declaring variables in JavaScript

- What is it?

- Okay...but what does it do?

- What is it good for?

- When should I use something else?

- So when should I use it?

The basics: declaring variables

Let's begin at the beginning: variable declarations declare variables. This may seem obvious to many, but in practice we often confuse variables with values, and it is important, particularly for this conversation, that we are clear on the differences.

A variable is a binding between a name and a value. It's just a box, not the contents of the box, and the contents of the box may vary either in part or in whole (hence the term 'variable').

The kind of box you use, that is, the declarator you use to create a binding, defines the way it can be handled by your program. And so when it comes to the question of, "How should I declare my variables?" you can think of the answer in terms of finding a box for your data that is best suited to the way you need to manipulate it.

The specifics: declaring variables in JavaScript

At the time of this writing, JavaScript gives us these tools for declaring our variables:

varletconst

💡 The

functionkeyword is not, in fact, a variable declarator, but it can create a bound identifier. I won't focus on it here; it's a bit special because it can only bind identifiers to values of a particular type (function objects), and so has a rather undisputed usage.

Why so many options? Well, the simple answer is that in the beginning, there was only var; but languages evolve, churn happens, and features come (but rarely go).

One of the most useful features in recent years was the addition of block scoping to the ECMAScript 2015 Language specification (a.k.a. ES6), and with it came new tools for working with the new type of scope.

In this post, we'll dive into the behavior of one of these new block-scope tools: let.

What is it?

Block scoping in JavaScript is wonderful. It gives us the ability to create scopes on-demand by "slicing up" a function into as many encapsulated bits of scope as we deem necessary, without the need for more functions.

But it would be rather useless without the ability to declare variables which exist only within these 'blocks' of scope.

Enter let.

let...declarations define variables that are scoped to the running execution context's LexicalEnvironment. The variables are created when their containing Lexical Environment is instantiated but may not be accessed in any way until the variable's LexicalBinding is evaluated. A variable defined by a LexicalBinding with an Initializer is assigned the value of its Initializer's AssignmentExpression when the LexicalBinding is evaluated, not when the variable is created. If a LexicalBinding in aletdeclaration does not have an Initializer the variable is assigned the valueundefinedwhen the LexicalBinding is evaluated.

Source: ECMAScript 2019 Language Specification, §13.3.1

Okay...but what does it do?

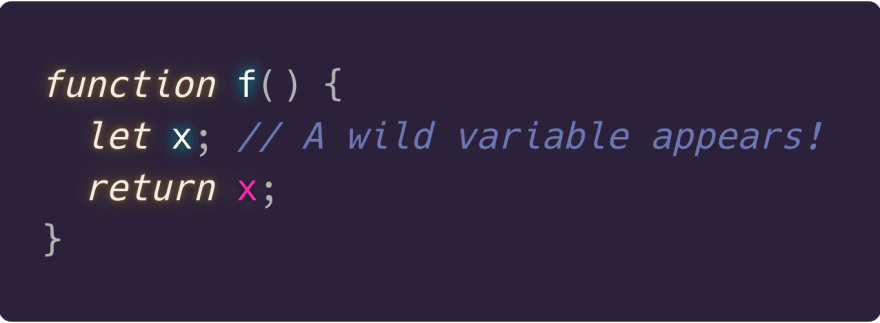

Translation? 🤨 Let's learn by doing.

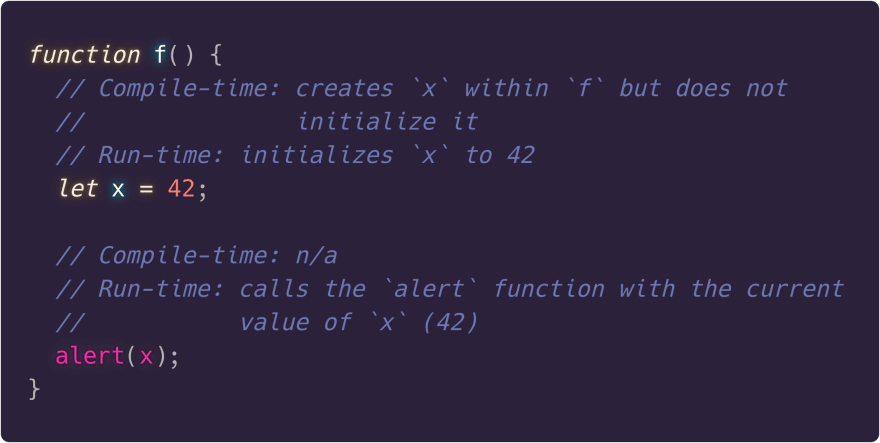

let, as its name so aptly denotes, names a variable and lets me use it.

During compilation, that variable is

- scoped to the nearest enclosing lexical environment (i.e. a block, a function, or the global object) and

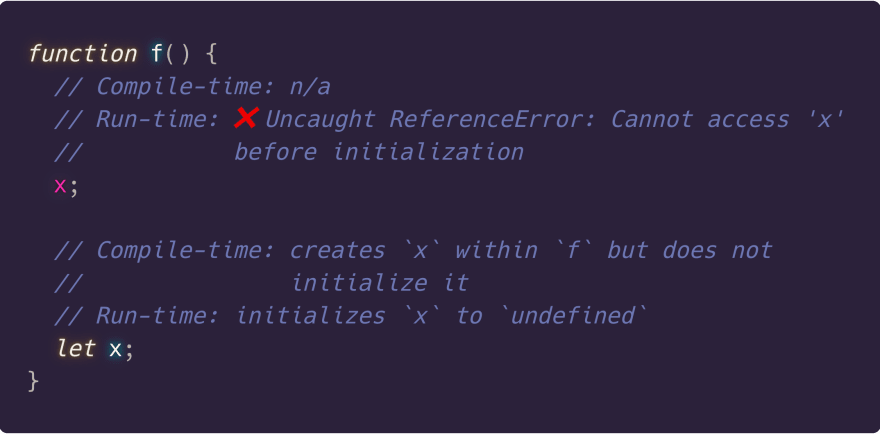

- created but not initialized during the instantiation of that scope

💡 You might come across the term "variable hoisting" in your JS travels: it refers to this 'lifting' behavior of the JS compiler with respect to creating variables during instantiation of the scope itself. All declarators hoist their variables, but the accessibility of those variables varies with the tool you use.

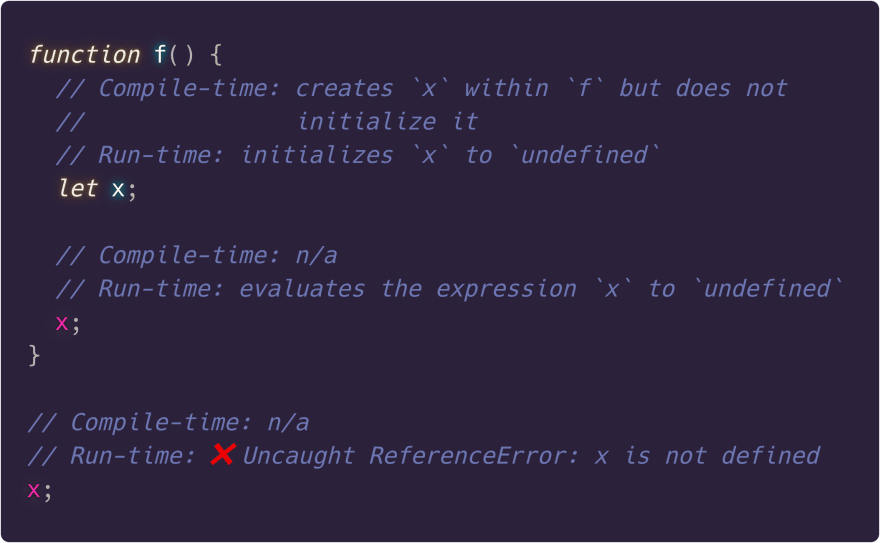

At run-time, references to my variable are evaluated and manipulated.

⚠️ In JavaScript error messages, "not defined" is not the same thing as having a value of

undefined😓 The term "not defined," in this context, should really be "not declared."

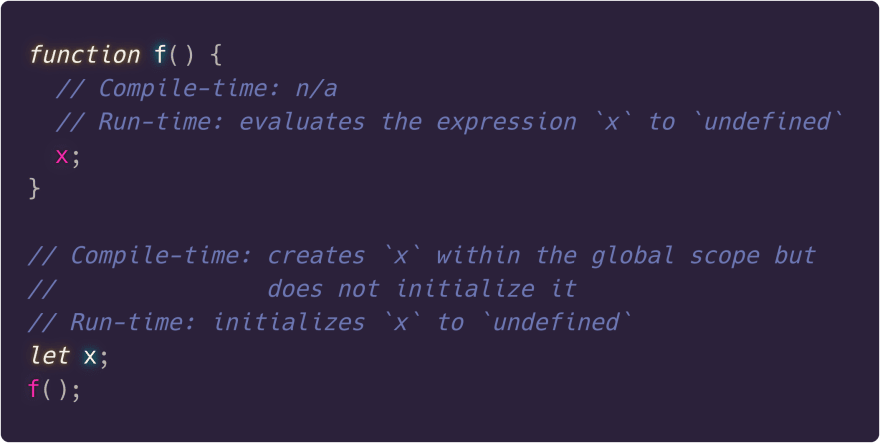

A run-time reference to a variable declared with let is not valid unless it occurs after the variable declaration, with respect to the current flow of execution, not necessarily the "physical" location of the declaration in my code. For example, this is valid:

But this will give me a run-time error:

If I combined my let declaration with a value assignment, that value doesn't go into the box until the assignment is evaluated, and evaluation happens at run-time.

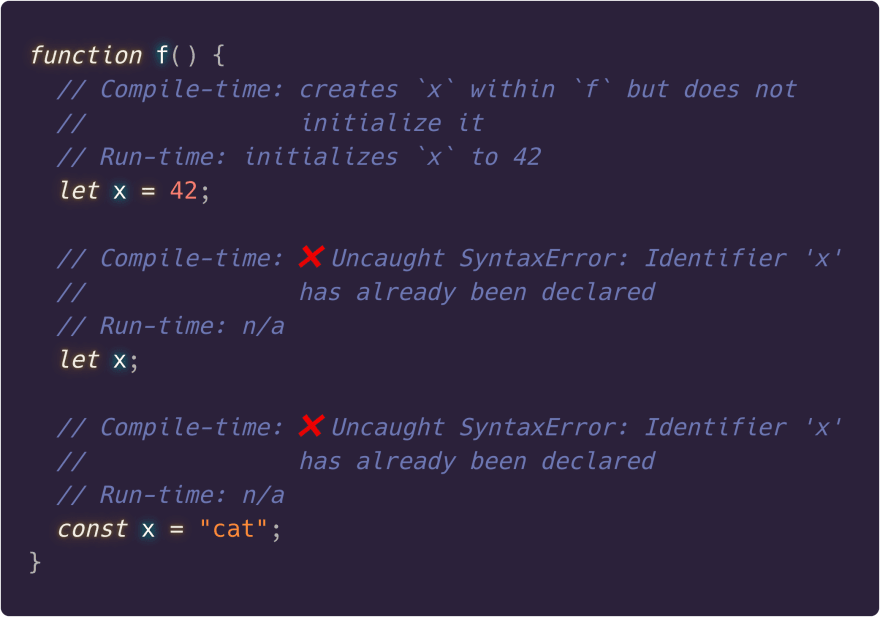

Furthermore, additional declarations of the same name in the same scope using let or const are not allowed: the name is essentially reserved by the first declaration encountered by the compiler.

What is it good for?

let, like var and const, gives the ability to encapsulate, manipulate, share, and hide data in boxes within my JavaScript.

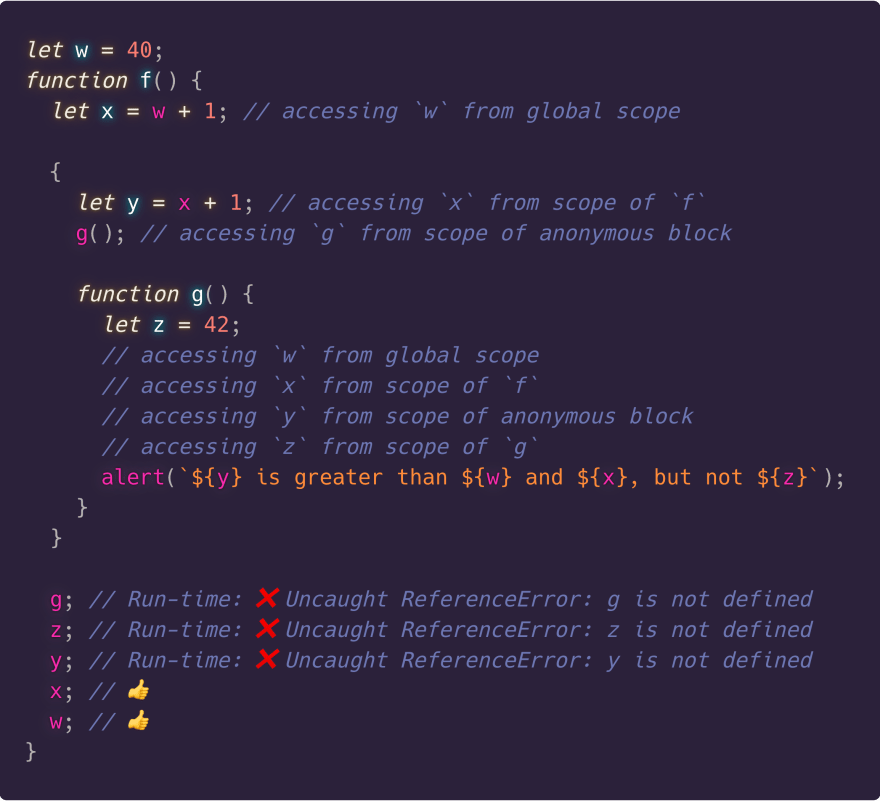

But unlike var, let restricts access to my box to the nearest enclosing lexical environment, not merely the closest function, and so let really shines at close-quarters data management.

In JavaScript, functions have lexical environments, but so do blocks, and this ability to reduce the scope of a variable and hide my data even from the nearest enclosing function is where the strength of let lies.

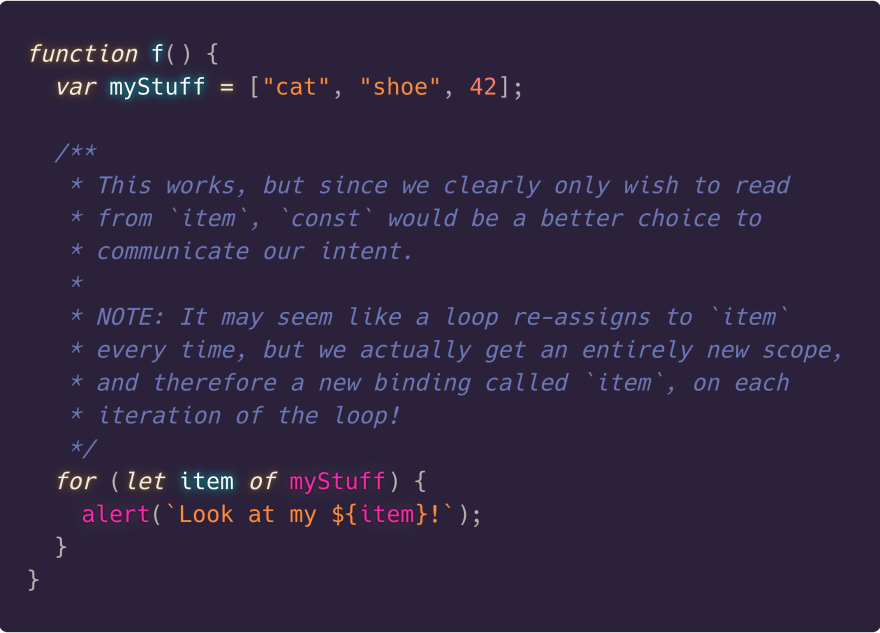

With let, like var, I am free to replace the contents of my box with something different or new any time I might need, as long as have access to it, making it a great choice for tracking changes over time in situations where an immutable approach to managing block-level state is not practical to implement.

And since functions inherit the environment of their parents thanks to closure, a function nested within such a block can access the let (and var and const) bindings of their parent scopes, but not vice-versa.

When should I use something else?

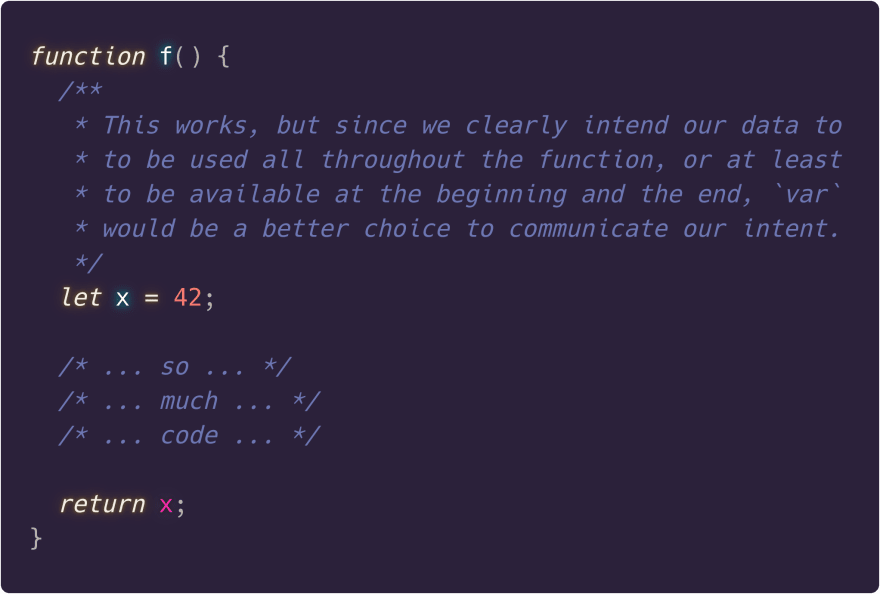

Sometimes, I need to manage state that is accessible across an entire function of decent size, not just a short block of code. Since let scopes my data to the nearest lexical environment, it will work for this purpose, but it communicates the wrong thing to my readers and so it's not the best tool for this job. In this situation, var is better.

Sometimes, I want a box that only holds one thing throughout my program, and/or I want my readers to know I don't intend to make changes to the data I put in it. Since let makes boxes that are always open to having their contents replaced, it communicates the wrong thing and so it's not the best tool for this job. In this situation, const is better.

Using let inappropriately can hurt the readability and maintainability of my code because I'm communicating the wrong thing and not encapsulating my data as well as I could be.

To learn how to communicate better in my code, I dove into the other tools available and wrote about what I found:

So when should I use it?

I prefer let for holding values that I know will only need names for a short time, and ensure they are enclosed by some sort of block.

The block could be something like an if statement, a for loop, or even an anonymous block; the main value of let is in keeping variables close to where they are used without exposing them to the wider world of the enclosing function.

If a function definition is particularly short, say only two or three lines long, I may prefer to use a let for top-level function bindings, but in this case the value over var is entirely in what it communicates to my readers: this variable is short-lived, you can forget about it soon and be at peace 😌.

If, during the course of development, I find myself wanting wider access to my let bindings, I can move my declaration into one of its surrounding scopes. (But if it ends up at the top level of a function, or out into the global scope, I tend to swap it out for var to more effectively communicate "this data is widely used and subject to change" to my readers.)

Every tool has its use. Some can make your code clearer to humans or clearer to machines, and some can strike a bit of balance between both.

"Good enough to work" should not be "good enough for you." Hold yourself to a higher standard: learn a little about a lot and a lot about a little, so that when the time comes to do something, you've got a fair idea of how to do it well.

Top comments (0)