First of all, don’t ask

I have no idea where this idea came from, it just happened. I keep saying “I’m not especially proud of this” but in reality? I sort of am because it’s funny as shit (pun intended). Some projects came across my twitter feed that included (I shit you not) a 3-D printable model of the  emoji. I remember nothing else about that project, but you’d better believe that I went straight for that STL file!

emoji. I remember nothing else about that project, but you’d better believe that I went straight for that STL file!

It then sat festering for a few weeks (if you’re not comfortable with lots of shitty jokes, bail out now. Fair warning.). I knew I would do something with it, I just didn’t know what I’d do. And then it hit me. I had a bunch of gas sensors lying around (if this surprises you, you really don’t know me at all). And then it hit me! A bathroom stink sensor and alert system!! But my shit doesn’t stink (shut up!) so where to deploy it? Eureka moment number 2! Our best friends’ house, where all events are always held, has what we all call “The Hardest Working Bathroom in Holly Springs”. There are regularly 20 people over there for dinner, or some other event, and that little powder room takes the brunt of it all.

Enter the Stink Detector

First thing was to 3-D print the little shit. To make sure I could fit the proper LEDs in it to make it light up the way I want it to. And no, you cannot make anything light up brown. If you’re really interested in why you can’t make brown light, you can go watch this video, but the dude is way weirder than I am. Again, fair warning. So anyway, I printed it, and lo and behold, the LED controller I wanted to use fit (almost) perfectly! I had to clip a couple of corners off the PCB, but no harm was done, and I got a light-up poop emoji!

I’ve also scaled it to 150% and I’m considering printing it that way just because, well, you know, bigger shit is better shit! So, how did I light this shit up? Actually, very simply. I buy these Wemos D1 Mini boards in bulk (like 20 at a time, since they’re only $2.00 each — more expensive if you buy them from Amazon, but if you buy them from Ali Express in China, they can be as cheap as $1.50 each) and I buy matching tri-color LED shields to go with them. My friends Andy Stanford-Clark got me started on these things with his ‘Glow Orbs” If you want to read more on the specifics of Glow Orbs, Dr. Lucy Rogers wrote a whole thing about them here. Turns out she built a Fart-O-Meter and used a GlowOrb as well. I had no idea until Andy told me.

For a Getting Started tutorial on the Wemos D1, see this article. I know a lot of folks write up full, detailed tutorials, etc. for this stuff but, frankly, I’m too lazy so I mostly just tell you what I’ve done. I’ll give the gory details where it matters.

So anyway, since I do this shit all the time, I have my poop-light listen to an MQTT broker for messages about what color to display. I’m still working out the detailed color levels as I calibrate things. I’ll cover the specifics of how messages get sent and received in a bit.

The stink detector itself is also being run on a Wemos D1 Mini with an MQ-4 Methane sensor that also supposedly measures H2 and an SGP-30 Air Quality sensor that measures Volatile Organic Chemicals (VOCs) and a really shitty version of CO2 which should never be trusted. I’ve done a lot of work with CO2 sensors, and these eCO2 sensors aren’t worth a shit. Seriously, never trust them. I’m awaiting delivery on some more, better gas sensors like an MQ-136 Sulphur Dioxide sensor and others. I’ll likely deploy them all and then invent some complicated but entirely arbitrary algorithm for deciding what is ‘smelly’. Stay tuned for that.

Building the Stink Sensor

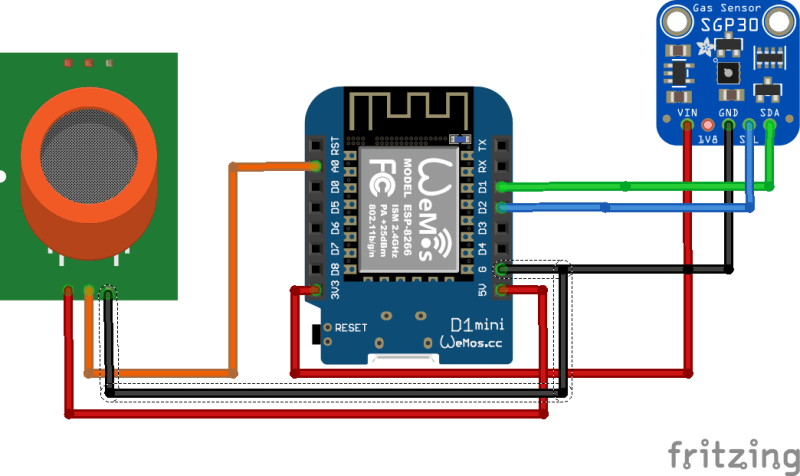

As I said, I’m currently using a Wemos D1 Mini with an MQ-4 Methane Sensor and an SGP-30 air quality sensor. You can buy them yourself if you plan to build this thing. I’ll update this with other sensors as I add them, maybe. Here’s how to wire everything up:

It’s important to note that the MQ-4 requires 5v whereas the SGP-30 only needs 3.3v. The MQ-4 is a straight analog sensor, so wiring it to one of the Analog inputs works fine. The SGP-30 is an I2C sensor, so it’s wired SDA<–>D1 and SCL<–>D2 which are the default I2C pins on the Wemos (which I have to look up every single time). When you apply 5v via the USB the MQ-4 gets straight 5v and the SGP-30 gets 3.3v via the onboard voltage regulator. Now, how do you actually get data off of these sensors? Well, that’s next, of course!

Reading Stink

The SGP-30 has a library for it provided by Adafruit (of course) so you’ll need to add that library to your Arduino IDE and then include it in your project.

#include <Adafruit_SGP30.h>

#include <Wire.h>

You will then create and SGP30 object and initialize it in your setup routine:

Adafruit_SGP30 sgp;

Creates the object and then:

if (! sgp.begin()){

Serial.println(“Sensor not found :(“);

while (1);

}

initializes the sensor. If you haven’t wired the sensor correctly, the whole thing will hang, so make sure you’ve wired it up correctly!

Reading the VOC is pretty simple after that:

if (! sgp.IAQmeasure()) {

Serial.println(“Measurement failed”);

return;

}

Serial.print(“TVOC “); Serial.print(sgp.TVOC); Serial.print(” \t”);

Serial.print(“Raw H2 “); Serial.print(sgp.rawH2); Serial.print(” \t”);

Serial.print(“Raw Ethanol “); Serial.print(sgp.rawEthanol); Serial.println(“”);

The sgp object is returned with all the readings in it, so it’s pretty easy. The MQ-4 sensor is a little more tricky. It’s an analog sensor, which means that it really just returns a raw voltage reading, which scales (somewhat) with the gas concentration. Lucky for me, someone provided a nice function to turn the raw voltage into a ppm (Parts Per Million) reading for the methane, so that’s required as well:

int NG_ppm(double rawValue){

double ppm = 10.938*exp(1.7742*(rawValue*3.3/4095));

return ppm;

}

Yeah, maths. I have no idea how it works, but it seems to, so I’m going with it because I’m shitty at math and have to trust someone smarter than me (which is most people, frankly). So now I can read the raw voltage on the analog pin, and then convert that to a reading of ppm, which is what we really want.

int sensorValue = analogRead(A0); // read analog input pin 0

int ppm = NG_ppm(sensorValue);

Cool! So, now that we can read the gas levels how do we tie all this together?

Don’t Use A Shitty Database!

Of course I work for a database company, so we’re going to use that one. Actually, even if I didn’t work for this particular database company, I’d still use it because, for IoT data like this, it’s just really the best solution. We will send all our data to InfluxDB and then we can see how to alert the glowing poop to change colors. So, how do we send data to InfluxDB? It’s super simple. We use the InfluxDB library for Arduino, of course!

#include <InfluxDb.h>

#define INFLUXDB\_HOST “yourhost.com”

#define INFLUX\_TOKEN “yourLongTokenStringForInfluxDB2”

#define BATCH\_SIZE 10

Influxdb influx(INFLUXDB\_HOST);

A couple of things to note here. I’m using InfluxDB 2.0, which is why I need the token. I have defined a BATCH_SIZE because writing data is much more efficient if we do it in batches rather than individually. Why? Well, I’m glad you asked! Each write to the database happens over the HTTP protocol. So when you want to do that, you have to set up the connection, write the data, and then tear down the connection. Doing this every second or so is expensive, from a power and processor perspective. So it’s better to save up a bunch of datapoints, then do the setup-send-teardown cycle once for all of it.

So now we have an Influxdb object initialized with the correct server address. In the setup() function we have to complete the configuration:

influx.setBucket(“myBucket”);

influx.setVersion(2);

influx.setOrg(“MyOrg”);

influx.setPort(9999);

influx.setToken(INFLUX_TOKEN);

That’s literally it. I’m all set up to start writing data to InfluxDB, so let’s see how I do that:

if (batchCount >= BATCH_SIZE) {

influx.write();

Serial.println(“Wrote to InfluxDB”);

batchCount = 0;

}

InfluxData row(“bathroom”);

row.addTag(“location “, “hsbath”);

row.addTag(“sensor1”, “sgp30”);

row.addTag(“sensor2”, “mq-4”);

row.addValue(“tvoc”, sgp.TVOC);

row.addValue(“raw_h2”, sgp.rawH2);

row.addValue(“ethanol”, sgp.rawEthanol);

row.addValue(“methane”, ppm);

influx.prepare(row);

batchCount +=1;

delay(500);

In the first part, I check to see if I’m up to my batch limit and if I am, I write the whole mess out to the database, and reset my count. After that, I create a new row for the database and add the tags and values to it. Then I ‘prepare’ the row which really just adds it to the queue to be written with the next batch. Increase the batch count, and sit quietly for 500ms (½ a second). Then we do the whole thing again.

Let’s go to the database and see if I have it all working:

I’d say that’s a yes! Now that it’s all there, it’s time to send updates to the glowing poop!

For that, we’re going to create a Task in InfluxDB 2.0. And I’m going to call it ‘poop’ because even I don’t want a task called ‘shit’ in my UI.

And here’s the task I created:

import “experimental/mqtt”

option task = {name: “poop”, every: 30s}

from(bucket: “telegraf”)

|> range(start: –task.every)

|> filter(fn: (r) =>

(r._measurement == “bathroom”))

|> filter(fn: (r) =>

(r._field == “tvoc”))

|> last()

|> mqtt.to(

broker: “tcp://yourmqttbroker.com:8883”,

topic: “poop”,

clientid: “poop-flux”,

valueColumns: [“_value”],

)

Since there’s a lot going on there, I’ll go through it all. First off, the MQTT package I wrote is still in the “experimental” package, so you have to import that in order to use it. If you look above in the image of the data explorer you can see that I’m storing everything in my “telegraf” bucket, and the “bathroom” measurement. Right now, I’m only keying off of the “tvoc” reading. Once I change that, I’ll update this task with the formula that I use. I’m just grabbing the last reading over the past 30 seconds. I then fill out the details for the MQTT broker I am using, and the topic to submit to, and off it goes! That’s it for the task!

Lighting Shit Up!

So as you recall, we put a WEMOS D1 mini with a tri-color LED on it into the printed poop. Now it’s time to light that shit up! Since we’re writing values out to an MQTT broker, all we really need to do is connect that WEMOS to the MQTT broker, which, thankfully, is really straightforward.

You need a bunch of WiFi stuff (you also need this in the sensor code, by the way):

#include <ESP8266WiFi.h>

#include <DNSServer.h>

#include <ESP8266WebServer.h>

#include <WiFiManager.h>

#include <PubSubClient.h>

#include <Adafruit_NeoPixel.h>

#include <ESP8266mDNS.h>

#include <WiFiUdp.h>

#define LED_PIN D2

#define LED_COUNT 1

// update this with the Broker address

#define BROKER “mybroker.com”

// update this with the Client ID in the format d:{org\_id}:{device_type}:{device_id}

#define CLIENTID “poop-orb”

#define COMMAND_TOPIC “poop”

int status = WL_IDLE_STATUS; // the Wifi radio’s status

WiFiClient espClient;

PubSubClient client(espClient);

Some of these are things that also correspond to things in your InfluxDB Task, like the COMMAND_TOPIC, and the BROKER. so make sure you get those correct between the two. That’s all the stuff you have to have defined (I’m not going through how to get the WiFi setup and configured as there are hundreds of tutorials on doing that for Arduino and ESP8266 devices.).

In your setup() function you will need to configure your MQTT Client (PubSubClient) object and subscribe to your topic as well as set up your LED. I use the Adafruit NeoPixel library because it’s super easy to use.

client.setServer(BROKER, 8883);

client.setCallback(callback);

client.subscribe(COMMAND_TOPIC);

Adafruit_NeoPixel pixel = Adafruit_NeoPixel(1, 4); // one pixels, on pin 4

//pin 4 is “D2” on the WeMoS D1 mini

Your main loop is pretty short for this, as the PubSubClient handles a lot of the timing for you:

void loop() {

if (!client.connected()) {

reconnect();

}

// service the MQTT client

client.loop();

}

You will, of course, need the callback routi, and this is where the magic happens, so let’s look at that now.

void callback(char* topic, byte* payload, unsigned int length) {

char content[10];

String s = String((char *)payload);

s.trim();

Serial.print(“Message arrived on “);

Serial.print(COMMAND_TOPIC);

Serial.print(“: “);

unsigned char buff[256] {};

s.getBytes(buff, 256);

buff[255] = ‘\0‘;

s = s.substring(s.indexOf(“=”) + 1, s.lastIndexOf(” “) );

s.trim();

int c = s.toInt();

String col = “”;

if (c > 100.0 ) {

col = “ff0000”;

} else if (c > 90.0 ) {

col = “ff4000”;

} else if (c > 80.0 ) {

col = “ffbf00”;

} else if (c > 70.0 ) {

col = “bfff00”;

} else if (c > 60.0 ) {

col = “40ff00”;

} else if (c > 50.0 ) {

col = “00ff40”;

} else if (c > 40.0 ) {

col = “00ffbf”;

} else if (c > 10.0 ) {

col = “00bfff”;

} else {

col = “bf00ff”;

}

long long number = strtoll(&col[0], NULL, 16);

int r = number >> 16;

int g = number >> 8 & 0xFF;

int b = number & 0xFF;

uint32_t pCol = pixel.Color(r, g, b);

colorWipe(pCol, 100);

}

Yeah, it’s nutty. Mostly because I use this same code in a bunch of different places. Sometimes I want the hex color, sometimes I want the RGB color, so I can go either way here. It looks shitty, but it works for me. All this does is get the message from the MQTT broker, and pull out the numeric value (through experience, I know that the MQTT message comes in the following format:

bathroom _value=566 1583959496007304541

So I know I can index into it to the = sign and the (space character) and come back with the numeric value. From there, it’s just scaling the value to the color and turning on the LED! After that, the poop glows when you shit! And the color changes depending on how stinky it is. The VOC value isn’t really a very good value (especially if you tend to use some sort of poop-spray to hide your mis-deed. Most of those are nothing but VOCs and that will spike the numbers, Which is why I’m awaiting the new sensors so I can get lots of gas values and see which one is most indicative of stink. Or which ones, more accurately. After that I’ll come up with some algorithm to properly scale the stink level based on the various gas levels. Then deploy to the Hardest Working Bathroom in Holly Springs.

And yes, they are game to have the stink-o-meter deployed over there.

Get your own shit

So, if you want to build one yourself … first you’ll need to print your own shit. You can download the STL file here. I’ll see if I can clean up all this code and put it in my GitHub. Feel free to Follow Me on Twitter and reach out with questions or comments!

As a final word, please, for the love of all that’s holy, wash your damned hands. 60% of men and 40% of women don’t wash their hands after using the toilet and that is disgusting. And now it makes you a disease vector. So Wash. Your. Hands!

Top comments (0)