Back in 2009, I challenged myself to write one blog post per week for the entire year. I had read that the best way to gain more traffic to a blog was to post consistently. One post per week seemed like a realistic goal due to all the article ideas I had but it turned out I was well short of 52 ideas. I dug through some half-written chapters what would eventually become Professional JavaScript and found a lot of material on classic computer science topics, including data structures and algorithms. I took that material and turned it into several posts in 2009 and (and a few in 2012), and got a lot of positive feedback on them.

Now, at the ten year anniversary of those posts, I've decided to update, republish, and expand on them using JavaScript in 2019. It's been interesting to see what has changed and what hasn't, and I hope you enjoy them.

What is a linked list?

A linked list is a data structure that stores multiple values in a linear fashion. Each value in a linked list is contained in its own node, an object that contains the data along with a link to the next node in the list. The link is a pointer to another node object or null if there is no next node. If each node has just one pointer to another node (most frequently called next) then the list is considered a singly linked list (or just linked list) whereas if each node has two links (usually previous and next) then it is considered a doubly linked list. In this post, I am focusing on singly linked lists.

Why use a linked list?

The primary benefit of linked lists is that they can contain an arbitrary number of values while using only the amount of memory necessary for those values. Preserving memory was very important on older computers where memory was scarce. At that time, a built-in array in C required you to specify how many items the array could contain and the program would reserve that amount of memory. Reserving that memory meant it could not be used for the rest of the program or any other programs running at the same time, even if the memory was never filled. One memory-scarce machines, you could easily run out of available memory using arrays. Linked lists were created to work around this problem.

Though originally intended for better memory management, linked lists also became popular when developers didn't know how many items an array would ultimately contain. It was much easier to use a linked list and add values as necessary than it was to accurately guess the maximum number of values an array might contain. As such, linked lists are often used as the foundation for built-in data structures in various programming languages.

The built-in JavaScript Array type is not implemented as a linked list, though its size is dynamic and is always the best option to start with. You might go your entire career without needing to use a linked list in JavaScript but linked lists are still a good way to learn about creating your own data structures.

The design of a linked list

The most important part of a linked list is its node structure. Each node must contain some data and a pointer to the next node in the list. Here is a simple representation in JavaScript:

class LinkedListNode {

constructor(data) {

this.data = data;

this.next = null;

}

}

In the LinkedListNode class, the data property contains the value the linked list item should store and the next property is a pointer to the next item in the list. The next property starts out as null because you don't yet know the next node. You can then create a linked list using the LinkedListNode class like this:

// create the first node

const head = new LinkedListNode(12);

// add a second node

head.next = new LinkedListNode(99);

// add a third node

head.next.next = new LinkedListNode(37);

The first node in a linked list is typically called the head, so the head identifier in this example represents the first node. The second node is created an assigned to head.next to create a list with two items. A third node is added by assigning it to head.next.next, which is the next pointer of the second node in the list. The next pointer of the third node in the list remains null. The following image shows the resulting data structure.

The structure of a linked list allows you to traverse all of the data by following the next pointer on each node. Here is a simple example of how to traverse a linked list and print each value out to the console:

let current = head;

while (current !== null) {

console.log(current.data);

current = current.next;

}

This code uses the variable current as the pointer that moves through the linked list. The current variable is initialized to the head of the list and the while loop continues until current is null. Inside of the loop, the value stored on the current node is printed and then the next pointer is followed to the next node.

Most linked list operations use this traversal algorithm or something similar, so understanding this algorithm is important to understanding linked lists in general.

The LinkedList class

If you were writing a linked list in C, you might stop at this point and consider your task complete (although you would use a struct instead of a class to represent each node). However, in object-oriented languages like JavaScript, it's more customary to create a class to encapsulate this functionality. Here is a simple example:

const head = Symbol("head");

class LinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

}

}

The LinkedList class represents a linked list and will contain methods for interacting with the data it contains. The only property is a symbol property called head that will contain a pointer to the first node in the list. A symbol property is used instead of a string property to make it clear that this property is not intended to be modified outside of the class.

Adding new data to the list

Adding an item into a linked list requires walking the structure to find the correct location, creating a new node, and inserting it in place. The one special case is when the list is empty, in which case you simply create a new node and assign it to head:

const head = Symbol("head");

class LinkedList {

constructor() {

this[head] = null;

}

add(data) {

// create a new node

const newNode = new LinkedListNode(data);

//special case: no items in the list yet

if (this[head] === null) {

// just set the head to the new node

this[head] = newNode;

} else {

// start out by looking at the first node

let current = this[head];

// follow `next` links until you reach the end

while (current.next !== null) {

current = current.next;

}

// assign the node into the `next` pointer

current.next = newNode;

}

}

}

The add() method accepts a single argument, any piece of data, and adds it to the end of the list. If the list is empty (this[head] is null) then you assign this[head] equal to the new node. If the list is not empty, then you need to traverse the already-existing list to find the last node. The traversal happens in a while loop that start at this[head] and follows the next links of each node until the last node is found. The last node has a next property equal to null, so it's important to stop traversal at that point rather than when current is null (as in the previous section). You can then assign the new node to that next property to add the data into the list.

The complexity of the add() method is O(n) because you must traverse the entire list to find the location to insert a new node. You can reduce this complexity to O(1) by tracking the end of the list (usually called the tail) in addition to the head, allowing you to immediately insert a new node in the correct position.

Retrieving data from the list

Linked lists don't allow random access to its contents, but you can still retrieve data in any given position by traversing the list and returning the data. To do so, you'll add a get() method that accepts a zero-based index of the data to retrieve, like this:

class LinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

get(index) {

// ensure `index` is a positive value

if (index > -1) {

// the pointer to use for traversal

let current = this[head];

// used to keep track of where in the list you are

let i = 0;

// traverse the list until you reach either the end or the index

while ((current !== null) && (i < index)) {

current = current.next;

i++;

}

// return the data if `current` isn't null

return current !== null ? current.data : undefined;

} else {

return undefined;

}

}

}

The get() method first checks to make sure that index is a positive value, otherwise it returns undefined. The i variable is used to keep track of how deep the traversal has gone into the list. The loop itself is the same basic traversal you saw earlier with the added condition that the loop should exit when i is equal to index. That means there are two conditions under which the loop can exit:

-

currentisnull, which means the list is shorter thanindex. -

iis equal toindex, which meanscurrentis the node in theindexposition.

If current is null then undefined is returned and otherwise current.data is returned. This check ensures that get() will never throw an error for an index that isn't found in the list (although you could decide to throw an error instead of returning undefined).

The complexity of the get() method ranges from O(1) when removing the first node (no traversal is needed) to O(n) when removing the last node (traversing the entire list is required). It's difficult to reduce complexity because a search is always required to identify the correct value to return.

Removing data from a linked list

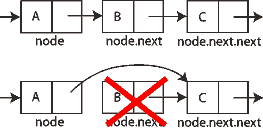

Removing data from a linked list is a little bit tricky because you need to ensure that all next pointers remain valid after a node is removed. For instance, if you want to remove the second node in a three-node list, you'll need to ensure that the first node's next property now points to the third node instead of the second. Skipping over the second node in this way effectively removes it from the list.

The remove operation is actually two operations:

- Find the specified index (the same algorithm as in

get()) - Remove the node at that index

Finding the specified index is the same as in the get() method, but in this loop you also need to track the node that comes before current because you'll need to modify the next pointer of the previous node.

There are also four special cases to consider:

- The list is empty (no traversal is possible)

- The index is less than zero

- The index is greater than the number of items in the list

- The index is zero (removing the head)

In the first three cases, the removal operation cannot be completed, and so it makes sense to throw an error; the fourth special case requires rewriting the this[head] property. Here is what the implementation of a remove() method looks like:

class LinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

remove(index) {

// special cases: empty list or invalid `index`

if ((this[head] === null) || (index < 0)) {

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

// special case: removing the first node

if (index === 0) {

// temporary store the data from the node

const data = this[head].data;

// just replace the head with the next node in the list

this[head] = this[head].next;

// return the data at the previous head of the list

return data;

}

// pointer use to traverse the list

let current = this[head];

// keeps track of the node before current in the loop

let previous = null;

// used to track how deep into the list you are

let i = 0;

// same loops as in `get()`

while ((current !== null) && (i < index)) {

// save the value of current

previous = current;

// traverse to the next node

current = current.next;

// increment the count

i++;

}

// if node was found, remove it

if (current !== null) {

// skip over the node to remove

previous.next = current.next;

// return the value that was just removed from the list

return current.data;

}

// if node wasn't found, throw an error

throw new RangeError(`Index ${index} does not exist in the list.`);

}

}

The remove() method first checks for two special cases, an empty list (this[head] is null) and an index that is less than zero. An error is thrown in both cases.

The next special case is when index is 0, meaning that you are removing the list head. The new list head should be the second node in the list, so you can set this[head] equal to this[head].next. It doesn't matter if there's only one node in the list because this[head] would end up equal to null, which means the list is empty after the removal. The only catch is to store the data from the original head in a local variable, data, so that it can be returned.

With three of the four special cases taken care of, you can now proceed with a traversal similar to that found in the get() method. As mentioned earlier, this loop is slightly different in that the previous variable is used to keep track of the node that appears just before current, as that information is necessary to propely remove a node. Similar to get(), when the loop exits current may be null, indicating that the index wasn't found. If that happens then an error is thrown, otherwise, previous.next is set to current.next, effectively removing current from the list. The data stored on current is returned as the last step.

The complexity of the remove() method is the same as get() and ranges from O(1) when removing the first node to O(n) when removing the last node.

Making the list iterable

In order to be used with the JavaScript for-of loop and array destructuring, collections of data must be iterables. The built-in JavaScript collections such as Array and Set are iterable by default, and you can make your own classes iterable by specifying a Symbol.iterator generator method on the class. I prefer to first implement a values() generator method (to match the method found on built-in collection classes) and then have Symbol.iterator call values() directly.

The values() method need only do a basic traversal of the list and yield the data that each node contains:

class LinkedList {

// other methods hidden for clarity

*values(){

let current = this[head];

while (current !== null) {

yield current.data;

current = current.next;

}

}

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this.values();

}

}

The values() method is marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate that it's a generator method. The method traverses the list, using yield to return each piece of data it encounters. (Note that the Symbol.iterator method isn't marked as a generator because it is returning an iterator from the values() generator method.)

Using the class

Once complete, you can use the linked list implementation like this:

const list = new LinkedList();

list.add("red");

list.add("orange");

list.add("yellow");

// get the second item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "orange"

// print out all items

for (const color of list) {

console.log(color);

}

// remove the second item in the list

console.log(list.remove(1)); // "orange"

// get the new first item in the list

console.log(list.get(1)); // "yellow"

// convert to an array

const array1 = [...list.values()];

const array2 = [...list];

This basic implementation of a linked list can be rounded out with a size property to count the number of nodes in the list, and other familiar methods such as indexOf(). The full source code is available on GitHub at my Computer Science in JavaScript project.

Conclusion

Linked lists aren't something you're likely to use every day, but they are a foundational data structure in computer science. The concept of using nodes that point to one another is used in many other data structures are built into many higher-level programming languages. A good understanding of how linked lists work is important for a good overall understanding of how to create and use other data structures.

For JavaScript programming, you are almost always better off using the built-in collection classes such as Array rather than creating your own. The built-in collection classes have already been optimized for production use and are well-supported across execution environments.

This post originally appeared on the Human Who Codes Blog on January 8, 2019.

Top comments (0)